The Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative launched in 1996—and complemented in 2005 by the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI)— has contributed to significantly reducing the debt burden in more than half of all [1], providing fiscal space to undertake much-needed developmental spending. Importantly, most of the LIDC beneficiaries from debt relief are African countries (29 out of 34 of the LIDCs), making this issue especially pertinent to the continent.

More than a decade later, fiscal deficits have widened and, in a handful of cases, public debt is getting close to where it was before debt relief, prompting the question of whether we are seeing the presage of a new debt trap. On one side of the debate are those who argue these concerns are premature, as average debt ratios in LIDCs have stabilized at relatively low levels. Not only that, they believe the recent uptick of debt experienced in some countries is justified by the scaling-up of investment that will pay off over the medium term. The skeptics, however, contend that capacity constraints and increasing reliance on non-concessional lending could jeopardize debt sustainability down the road (see, Reuters 2014 and Prizzon and Mustapha 2014). A new IMF study highlights the opportunities opened by the changing external financing landscape but also points to new risks and the needed policy responses.

What Are the Facts?

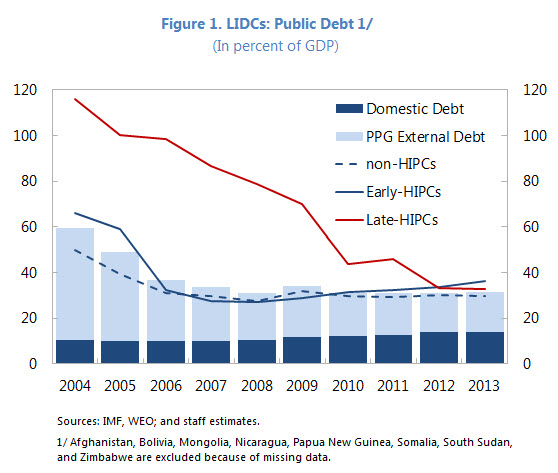

Public debt ratios have indeed declined below an average level of 35 percent of GDP over the last decade (Figure 1), but not all LIDCs are the same. Since 2007, debt ratios have dropped significantly in “late HIPCs” (countries that reached completion point after 2007) while the trend among “early HIPCs” is the reverse, with a few countries experiencing double digit increases (for example, Ghana and Malawi).Nevertheless, some three-quarters of LIDCs are currently assessed as being at low or moderate risk of external debt distress.

At the same time, bilateral creditors are taking on a more prominent role, and non-concessional external borrowing is on the rise with many “early-HIPCs” issuing international sovereign bonds for the first time, mainly to finance large infrastructure projects. The development of local currency bond markets has more recently fostered the rise of domestic debt in low-income countries (for example in Nigeria and Kenya).

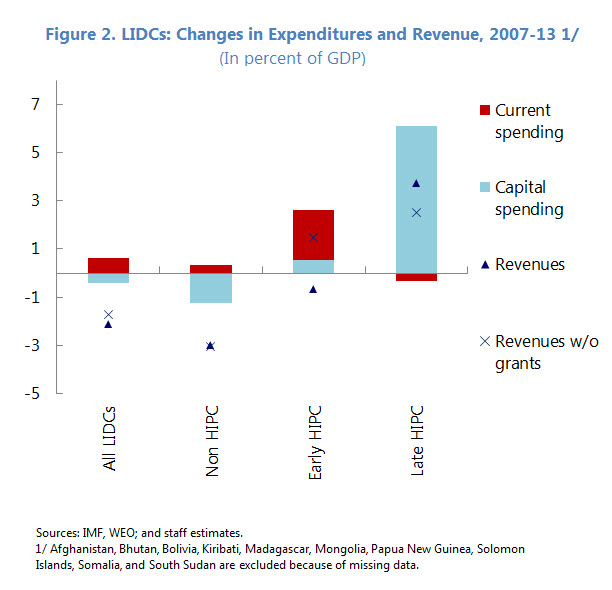

In parallel, the fiscal space in LIDCs has become more constrained since 2008 as deficits went up by about 3.5 percent of GDP. The weakening of the fiscal position is the immediate result of higher spending. But revenue mobilization efforts have also fallen short of what is needed to offset the impact of the ongoing decline in grants, particularly in non-HIPCs and “early-HIPCs” (Figure 2).

Are LIDCs Getting Value for Money?

Given large developmental needs, it is not surprising spending has gone up. But the real question is whether debt-financed spending will deliver benefits sufficient to cover outlays. In more than half of LIDCs, public investment was scaled up, significantly so in “late HIPCs.” But in about half of LIDCs the bulk of spending increases came from current outlays with public wages accounting for about 40 percent of current spending. Granted that some of these increases may have gone to priority areas such as health and education, but much has gone elsewhere.

In our view, the growth dividend and the sustainability of the scaling-up of spending cannot be taken for granted. In fact, concerns remain about the efficiency with which LIDCs can convert public investment into public capital—although the relative capital scarcity of LIDCs could imply high rate of returns on investment projects. Moreover, some large spending items, such as energy subsidies, are crowding out private investment and distorting resource allocation.

Seizing the Opportunities

So what did we learn? In reality, the immediate challenge for a majority of LIDCs is not debt sustainability, but rather how to take full advantage of the space afforded by low debt levels while maintaining macro-fiscal stability and minimizing the risks entailed by new sources of financing. This will require improvements in several areas:

- Strong budgetary institutions are needed to control spending and budget overruns while fiscal deficits should be anchored on a medium-term fiscal framework. This poses particular challenges in countries that have recently discovered natural resources (for example, Mozambique) where the fiscal framework should be taking into account the volatility of revenues and exhaustibility of resources.

- Many LIDCs still face a need to raise more revenue from their own tax bases, particularly given the prospective decline in grants.

- Improving developmental indicators is not only a matter of more resources but also improving spending efficiency—particularly investment project selection and management—to ensure appropriate rates of return (and thus repayment capacity).

- Comprehensive medium-term debt-management strategies should also be developed. This is particularly pressing for countries now gaining market access, that need to build institutional capacity to deal with increasing exposures to rollover, re-pricing and exchange rate risks.

[1] LIDCs are the 60 countries that fall below a modest per capita income threshold ($2,500 in 2011, based on gross national income) and are not conventionally viewed as emerging market economies.

Commentary

Financing for Development: New Opportunities or the Old Debt Trap?

November 5, 2014