Like many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Ghana’s impressive economic growth in recent decades, largely propelled by higher commodity prices such as cocoa and gold on the international market, has so far failed to re-structure the country’s economy. The broader Ghanaian economy continues to exhibit fragility and a weak adaptability to internal and external challenges with limited capacity to absorb shocks. More importantly, the impressive economic growth of recent years has not lead to the creation of sufficient employment, especially for the teeming youth who enter the labor market every year. Within the context of limited employment and other opportunities in the labor market, the development of entrepreneurial activity is seen as having a key role in this environment. This is because entrepreneurship can drive innovation and competition, and act as a catalyst for structural transformation of an economy and, consequently, a reduction in poverty.

While the literature on entrepreneurship is vast, little is known about the forms and characteristics of female entrepreneurship in Ghana in particular and sub-Saharan African countries in general. Following the first-ever Global Entrepreneurship Monitoring (GEM) survey in Ghana, we examined the reasons and effects of the relatively higher levels of entrepreneurial activities among women compared to their male counterparts.[1] More specifically, we examined women and entrepreneurship in Ghana, women’s motivation to start and operate businesses, the key challenges they face, and the overall impact on national development and poverty reduction.

Women and Entrepreneurship in Ghana

Even though in proportional terms, studies have indicated that both genders experience difficulty on the labor market, females tend to fare worse than their male counterparts [2]. For instance, the 2010 Population and Housing Census of Ghana indicates that although unemployment declined between 2000 and 2010, it was still relatively higher for women compared to men. Unemployment among males 15 years above declined from 10.1 percent in 2000 to 4.8 percent in 2010 compared to 10.7 percent to 5.8 percent for females for the same time period. This situation is partly due to the relatively low level of education and other constraints among females on the labor market. It is within this context that female participation in entrepreneurship becomes very important. Female-controlled businesses in Ghana often tend to be micro and small enterprises (MSEs) largely concentrated in the informal sector. This trend also hinders female success: MSEs in the informal sector are unable to expand because they are confronted with a myriad of challenges such as limited access to public infrastructure and services (water, electricity, etc.), cheap and long term credit, and new technologies.

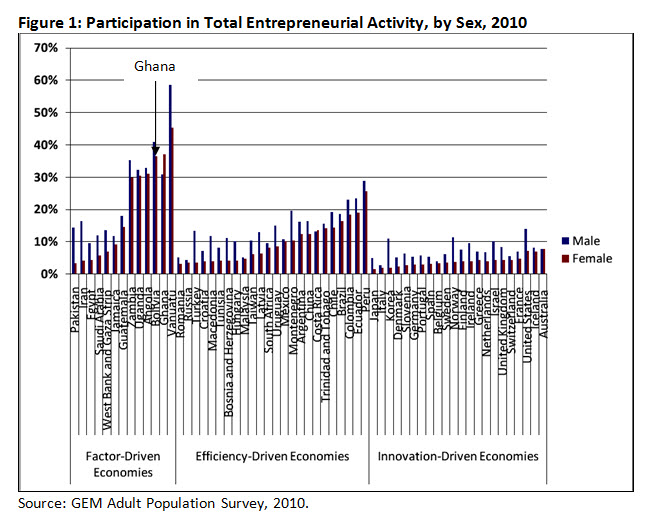

According to Yankson et al. (2011), across all countries in the world, societal views on culture, religion, and child care, and levels of education and development have serious implications for attitudes and opinions about working women. These societal views can weigh heavily against women entering the business world. Despite these challenges, the 2010 GEM survey revealed that in Ghana, women are more entrepreneurial than men—a condition which is an exception across all the GEM countries. Using a key measurement in GEM, the “total early stage entrepreneurial activity” (TEA),[3] the 2010 study revealed that—with the exception of Ghana—across all GEM countries male participation in entrepreneurial activity exceeds that of the female (see Figure 1). The TEA rate for Ghana was estimated at almost 60 percent for the females and 42 percent for males. In other words, unlike other countries, in Ghana there are fewer men than women starting businesses. The GEM study confirms the conclusions of other studies that have concluded that the number of female entrepreneurs in Ghana far outweigh the number of male entrepreneurs.

Women’s Motivations to Start Businesses

The growth of female entrepreneurs needs to be regarded as part of a broader process of social change that is marked by increases in the number of women in the workforce, including women in business. This process of social change is associated with increased education for women, postponement of early marriage, smaller family sizes and the increased desire for financial independence—all of which contribute to the growth of women-owned businesses.[4] In the view of Dzisi (2008), today, entrepreneurship is an accepted career path for women; it is even preferred to some degree as it is seen to have the potential to offer flexibility and independence that typical employment does not.

Though Ghanaian women have long been active in business, the effects of economic reform programs beginning in the mid-1980s have pushed more women into the informal sector, either as the sole providers or supplementers of household incomes.[5] The reforms ushered in an era of rising prices of basic needs, growing unemployment and underemployment of male partners, declining real income, and the growing demand to meet local levies for social amenities provision through user charges. Under these conditions, the necessity for female supportive income for the household became imperative and women’s income-generating activities became indispensable to family survival.[6]

Commenting on the factors that motivate women to starting business, Mumuni et al. (2013) note that these factors can be grouped as follows:

- No choice entrepreneurship: divorce; death of husband or breadwinner

- By chance entrepreneurship: marriage; retirement; friends

- Forced entrepreneurship: apprenticeship, imitation, independence, loss of job, love for wealth

- Informed entrepreneurship: education, mentoring, coaching, training

- Pure entrepreneurship: skills, interest, passion, in-born

Clearly, the myriad of reasons that motivate or drive women to engage in entrepreneurship could be simply classified under the labeling of necessity and opportunity-driven. In this direction, Mumuni et al.’s (2013) categorizations of no choice, by chance and forced entrepreneurships could be classified as necessity-driven entrepreneurship while informed and pure entrepreneurships could fall under opportunity-driven entrepreneurship.

Challenges

Although it has been argued that institutional, legal and regulatory frameworks for business development in Ghana are to a large extent gender neutral, certain social-cultural factors and structural conditions continue to militate against women entrepreneurship. Compared to their male counterparts, women in Ghana are poorer, have heavier time burdens, and are less likely to be literate. All these factors have negative impacts on women entrepreneurship although the regulatory, legal and institutional regimes of the country can be described as gender neutral.

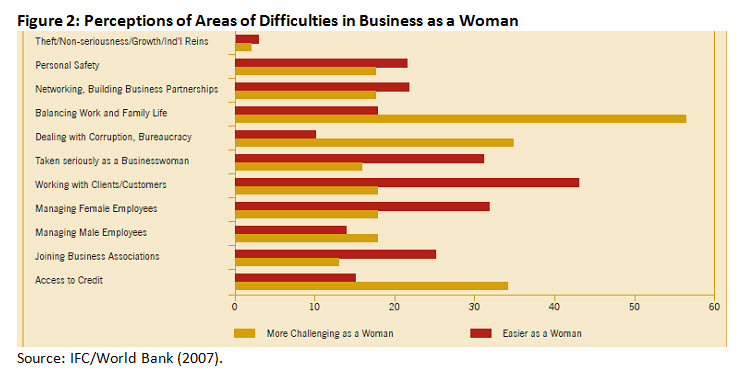

The recent study IFC/World Bank study, Voices of Women Entrepreneurs in Ghana, highlighted the issues, concerns and successes of female entrepreneurs in their own voices. The IFC/World Bank revealed several areas perceived by Ghanaian female entrepreneurs as particularly challenging, and three key areas stand out: balancing work and family life; dealing with corruption; access to credit and; managing male employees (see Figure 2).

Of all the perceived difficult areas that hinder women in business, the most critical is the balancing of work and family life. Culturally, a role has been carved for Ghanaian women as maintainers and caretakers of homes, a role that is often at odds with being a business owner. Women often struggle to balance the time it takes to run a business and the expectations of society in meeting family commitments.

Another key challenging area highlighted in many other studies is cultural practice regarding land and property ownership (especially inheritance) and its negative impacts on women entrepreneurship. Access to land is administered under customary law, which contains built-in discrimination against female land ownership. In addition, inheritance systems largely administered through traditional and cultural practices tend to discriminate against women—one can therefore understand the role of land as one of the range of constraints faced by female entrepreneurs. Furthermore, it has been argued that women’s limited access to start-up capital is related to access to credit, which in turn is correlated with formal property ownership. Therefore, the inability of women to own property has serious implications for access to credit as they have no property to use as collateral for start-up capital.

Conclusion

Economic and political reforms over the last three decades in Ghana have resulted in a stable socio-economic environment that has facilitated significant economic growth rates, with a strong focus on private sector development. These growth rates have not, however, generated significant employment opportunities in the private sector that is dominantly informal. In addition, economic liberalization and privatization have been associated with dwindling employment levels in the public sector, which in any case to a large extent favors individuals with relatively higher levels of education and skill training.

Despite women’s dominance in entrepreneurial activities in Ghana, women still face significant obstacles. In addition, the challenges of men and women’s entrepreneurship in Ghana cannot be separated from those of the informal sector in particular and the private sector development in general. Consequently, the policy response needs not to narrowly focus on promoting female entrepreneurship but to broadly resolve the constraints affecting the informal sector or entrepreneurship in general. In this way, support for female entrepreneurship should be viewed as one element of a comprehensive development policy drive that addresses the complex factors and relationships that influence women’s access to meaningful employment as well as contribution to national development. This approach will contribute to improvement in gender equity and promote human capital accumulation, women’s economic participation and beneficial economic growth effects.

Note:

George Owusu is an associate professor at the Institute of Statistical, Social & Economic Research (ISSER) at the University of Ghana, Legon. He can be reached at [email protected] or [email protected]. Peter Quartey and Simon Bawakyillenuo are an associate professor and research fellow, respectively, at ISSER. ISSER is one of the Brookings Africa Growth Initiative’s six local think tank partners based in Africa. This blog reflects the views of the authors only and does not reflect the views of the Africa Growth Initiative.

[1] The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) is the largest independent survey of entrepreneurship in the world, which is carried out yearly. It analyzes the relationship between the level of entrepreneurship and economic growth, and examines the conditions that foster and constrain entrepreneurship in each participating country. Over 60 countries have been involved in the GEM research consortium over the decades but very few have participated from Sub-Saharan Africa. Through ISSER’s research project titled Youth and Employment: The Role of Entrepreneurship in African Economies (YEMP), funded by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs/Danida, Ghana participated in the 2010 GEM global survey for the first time.

[2] Ghana Trade Union Congress (GTUC) 2005: Policies on Employment, Earnings and the Petroleum Sector, Accra: GTUC/UNDP.

[3] TEA is defined as the proportion of the total adult population of 18-64 years who are either a nascent entrepreneur or owner/manager of a new business (3-42 months old). This measurement takes into account of all the adult population and not simply those engaged in entrepreneurship.

[4] Fielden, S. and Davidson, M. 2005: International Handbook of Women and Small Business Entrepreneurship, Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

[5] Owusu, G. and Lund, R. 2004: Markets and women’s trade: Exploring their role in district development in Ghana, Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography. 58(3), pp. 113-124.

[6] Robertson, C. 1995: Comparative advantage: Women in trade in Accra, Ghana and Nairobi, Kenya. House-Midamba, B. and Ekechi, K.E. (eds.): African Market Women and Economic Power, London: Greenwood Press, pp. 99-119

Commentary

Are Ghana’s Women More Entrepreneurial Than its Men?

August 19, 2014