The ascension of Xi Jinping to the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has often been posited as a turning point for China’s policy in the South and East China Sea maritime disputes. As early as 2013, You Ji of the University of New South Wales assessed that Xi had been “instrumental in changing China’s passivity” into an assertive strategy to defend China’s claims. More recently Xue Gong of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore has argued that “China has become more assertive in the South China Sea since Xi became General Secretary of the CCP in 2012.” Xi himself seemed to encourage such a reading when he cited South China Sea island construction in his 2017 Party Congress work report declaring China had reached a new era marked by the transition under his leadership “from growing prosperous to getting strong.”

As we will see, the idea that China has pursued its maritime claims more assertively under Xi is accurate. Yet it is also potentially misleading, for China was already on such a trajectory long before Xi took power. It was from 2006 that Beijing began using law enforcement ships to expand its control of large swathes of disputed waters, withdrew from the dispute resolution procedures in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), started production of disputed offshore gas fields, and launched unilateral energy explorations and a campaign of coercion against rival claimants who sought to do the same.

What has really changed in China’s maritime policy since Xi Jinping took power? How has this compared with China’s policy direction over the preceding years? And what is the likely role of the CCP’s “Chairman of Everything” in the observed changes?

Declarative policy

China’s stated maritime policy under Xi Jinping has contained three notable elements. The first is the goal of building China into a “maritime great power” (海洋强国), which appeared for the first time in the CCP’s most authoritative political document, the political work report, at the 18th Party Congress in 2012, and was reaffirmed at the 19th in 2017.

This goal was in fact put forward by Jiang Zemin at the “Two Meetings” back in 2000. Jiang stated that “constructing a maritime great power is an important historic task, for which we must earnestly conduct research.” Since that time, it has progressively been upgraded in party-state documents, notably in the programmatic 2008 State Council document titled “Planning Outline for the Development of National Maritime Activities.” Evidently, building China into a maritime power has not been an initiative of Xi Jinping, but a methodically implemented party-state program dating back at least seven years before Xi was even transferred to Beijing.

The second element of Xi Jinping’s declared maritime policy addresses the tension between advancing China’s claims and avoiding military escalation. In the CCP’s dialectical policy-speak, this is known as the “unity of rights defense and stability maintenance” (维权维稳相统一). Xi’s remarks in a July 31, 2013, Politburo study session on maritime disputes—vowing never to compromise and calling for “coordinated planning of the two overall situations (两个大局) of rights defense and stability maintenance”—have often been taken as an expression of Xi’s more assertive maritime policy preferences.

But PRC policy statements have featured the rights-defense-stability-maintenance formulation since 2008 at the latest. What’s more, Xi’s phrasing explicitly referenced a signature foreign affairs directive of his predecessor, Hu Jintao: “coordinated planning of the domestic and international overall situations.” Hu issued this directive in 2006 with the goal of reining in uncoordinated policy actors that were harming China’s image. Once again, then, Xi’s hard-line policy rhetoric seems to reflect long-term consensus ideas rather than his distinct personal preferences.

The third feature of China’s declarative policy in the Xi era has been the indignant “no-acceptance, no-participation, no-recognition, no-implementation” response to the arbitration case brought on by the Philippines under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). In the July 2013 Politburo meeting, Xi declared that while China was peace-loving, it “absolutely will not give up its legitimate rights, much less sacrifice its national core interests.” This presaged an uncompromising response to the Philippines’ request for arbitration, which had been made six months earlier in January 2013.

But while the chairman probably paid close attention to the case, it is hard to imagine Beijing’s response being significantly different under another leader. As noted above, the PRC had withdrawn from the UNCLOS’s compulsory dispute resolution procedures in 2006, showing its intention to avoid international legal processes in regard to its maritime claims. Even more tellingly, in 2009 the PRC attached its infamous nine-dash line map to an official diplomatic document for the first time, suggesting—as had its 1998 Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) Law, which made reference to unspecified “historic rights” in addition to those ascribed by the UNCLOS—that the PRC did not consider its maritime claims to be bound by international law. As such, the PRC’s policy of non-acceptance and non-participation in the arbitration is also unlikely to have reflected the distinct influence of Xi Jinping as leader. Instead, it is probably better seen as a path-dependent, default response to what appeared from within party circles to be a serious attempt to delegitimize China’s claims.

Unilateral administration

Xi-era China’s most consequential move has been the massive expansion of its outposts in the Spratly Islands. The PRC’s artificial islands now dwarf the area of all the naturally formed features in the disputed archipelago. Two years of sustained land reclamation works turned once-precarious outposts perched atop submerged reefs into 1,300 hectares of new land, at enormous financial and ecological cost. This has been followed by construction of an array of infrastructure, including 3,000-meter military-grade runways, aircraft hangars, and deployment of anti-ship cruise missiles.

The island-building campaign is perhaps the strongest candidate for a policy change with Xi’s personal stamp. Indeed, Xi implicitly claimed the credit in his report to the 19th Party Congress when he lauded “South China Sea island construction” among the key achievements since the previous party congress—the one at which he took power.

Yet even in this case it is far from clear that Xi made the difference, rather than the PRC state’s increasing financial and technological means—particularly the dozens of large dredgers that performed the task. Not only does Beijing’s pursuit of this capability date back to the early 2000s, the island-building campaign was the latest in a long line of measures China has taken since the early 1980s to expand its presence in the Spratly Islands.1 Without doubt, this particular effort was on an entirely new scale—but Beijing’s intention to do what it can to strengthen its foothold in the Spratlys long precedes the current era. Xi has had far greater capabilities to draw upon in advancing that goal than his predecessors.

Another key pattern of unilateral action in Xi Jinping’s maritime policy has been regular Coast Guard patrols within 12 nautical miles of the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands. Although Japan still controls the disputed islands themselves, China’s new patrolling patterns have created a situation of overlapping administration of the territorial seas—a sovereign maritime space under international law.

The new pattern of patrolling was initiated in September 2012 in response to Japan’s transfer of three of the islands to central government control. Multiple sources have said that Xi Jinping personally oversaw China’s response to the crisis. However, even if we assume these anonymous reports to be true, there are good reasons to doubt whether Xi’s own policy preferences made a difference.

First, China’s policy toward the Diaoyu/Senkaku issue had been progressively hardening since 2006.2 This trend was manifest in August-September 2010 when, amid a major surge in state-sponsored PRC fishing near the disputed islands, a Chinese trawler rammed a Japanese Coast Guard ship. Beijing responded with further escalation, sending PRC fisheries patrols to linger just outside the territorial seas, even after Japan released the trawler’s captain and dropped legal proceedings against him.

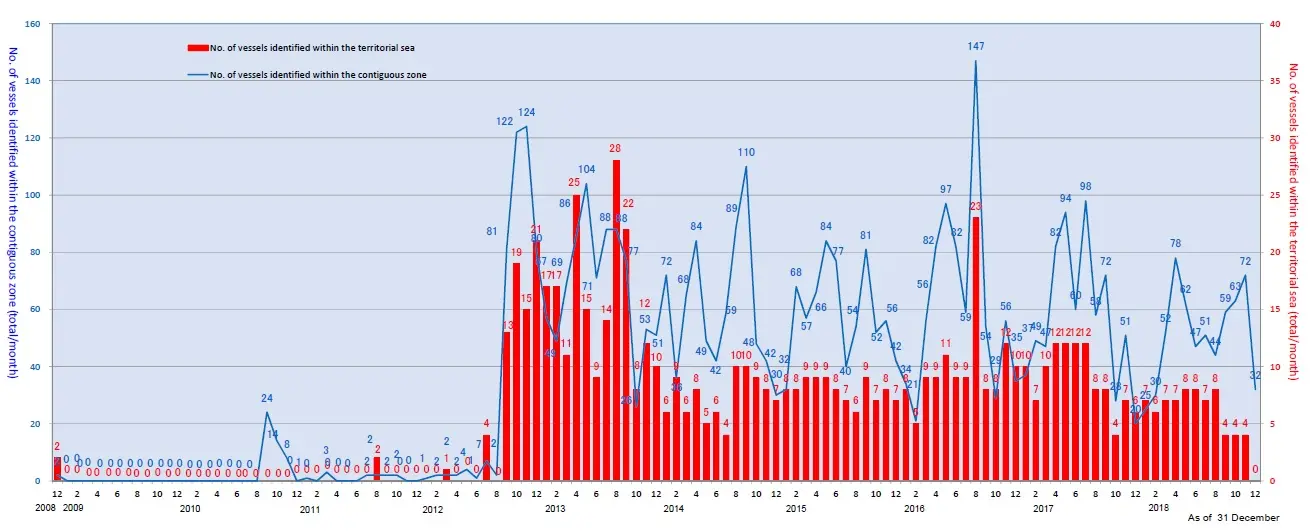

In the 12 months leading up to the 2012 crisis, Chinese patrol boats had entered the disputed territorial seas an unprecedented three times (Figure 1), and officials had spoken of the desirability of a regularized presence in the disputed waters. This suggests the new patrols, which have become regularized since 2012, may well have been part of China’s response to Japan’s nationalization of the islands even if another leader had been in charge.

Coercion at sea

New strands of coercive policy in China’s maritime disputes in the Xi era have been surprisingly rare, and most of the PRC’s coercive activities since Xi took power have continued Hu-era patterns of behavior.3 One example is the HYSY-981 oil rig operation, which followed an established pattern of unilateral offshore explorations in disputed waters, enforced by coercive on-water escorts. The PRC conducted this type of operation in similar areas in 2006 and 2007, leading to intense on-water clashes with Vietnam, and again in 2010. The difference in 2014 was that the PRC now possessed a gargantuan drilling rig and dozens more law enforcement ships to police the area.

Some Hu-era coercive activities at sea have actually been absent under Xi, notably the numerous cases of interference with Vietnamese and Philippine energy survey projects between 2007 and 2012. Still, two significant new policies of this type from the Xi era merit attention.

One was the November 2013 announcement of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the East China Sea, accompanied by threats of a military response for non-compliance.4 Hu Jintao reportedly refused the PLA Air Force’s proposals for an ADIZ during his tenure, but Xi Jinping was more receptive, according to Chinese analysts interviewed by the International Crisis Group (ICG). If so, this would make the East China Sea ADIZ a likely example of Xi Jinping’s impact.

Still, other PRC analysts told ICG that prior to 2013, the PLA Air Force did not possess sufficient capabilities to monitor and enforce the zone. If so, then like the massive island-building program, the ADIZ only become a viable policy option after Xi took power, so the impact of the leader on China’s policy may have been immaterial.

Another distinctly Xi-era coercive policy has been the threat to blockade the Philippines’ outpost on Second Thomas Shoal, in the form of a constant patrol boat presence at the shoal, from May 2013. This was probably intended as retaliation for the Philippines’ initiation of arbitration proceedings under the UNCLOS, perhaps in the hope of pressuring Manila to drop the case. As argued above, it is unlikely that the CCP would have accepted the Philippines’ arbitration and cooperated with the tribunal, regardless of the leader in charge. But unlike many of the cases examined above, it is conceivable that a more moderate leader would have refrained from taking the legal dispute onto the water in this manner. This leaves Second Thomas Shoal as a plausible example of Xi’s influence.

Policy implications

This article has argued that—so far—Xi Jinping’s leadership has made relatively little difference to China’s policy in the South and East China Sea disputes. This is counterintuitive because, as we have seen, China has become more assertive in a variety of ways since Xi took power. But it had already been on such a trajectory since 2006, and the current leader has had numerous important capabilities at his disposal that his predecessors did not. This finding raises three policy implications for the United States if it seeks to help maintain peace and stability in East Asia.

Chinese maritime policy has been following a largely path-dependent logic that is less susceptible to carrots and sticks than foreign policymakers may believe.

First, it suggests that, rather than reflecting individual politicians’ preferences, Chinese maritime policy has been following a largely path-dependent logic that is less susceptible to carrots and sticks than foreign policymakers may believe. As I have noted elsewhere, legal-administrative changes and capacity-building projects have had profound lagged effects on PRC policy in the South China Sea. In turn, this suggests the overall direction of the PRC’s policy in this domain has probably had less to do with United States policy—particularly its widely-perceived deficiency of “pushback” in the South China Sea—than commonly assumed.

Second, this analysis does not imply that Xi lacks the capability to influence PRC’s assertive behavior—it means his role has probably been more akin to a gatekeeper than an architect of China’s expansion of control over maritime East Asia. This suggests any attempt by Washington to use deterrence signaling to shape China’s behavior in this area will need to capture the attention of Xi himself, and convince him that the undesired course of action is against China’s, and his own, interests.

This would also imply that serious efforts to deter particular PRC behaviors will also need to consider ways of minimizing the costs to Xi’s personal legitimacy of complying. Proffered consequences for particular courses of potentially destabilizing PRC action—such as enclosure of some or all of the Spratly Islands within territorial sea baselines, or the occupation of any additional reefs or rocks—should be raised privately and directly in meetings of individual leaders, rather than conveyed publicly and left to be inferred by lower levels of the PRC bureaucracy.

There are signs that the Trump administration may be using increases in the frequency of Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs)—and publicity thereof—to pressure the PRC on other issues. A stable baseline of FONOP patrols provides valuable reassurance of U.S. commitment to stability in the region, but attempting to use FONOPs as a coercive tool would be a mistake, based on this paper’s analysis. For one thing, such patrols are not particularly provocative, and so may not attract the top leader’s attention. And for the same reason, the PRC’s on-water responses may be decided on at relatively low points in the PLA chain of command, raising risks of local accidents and miscalculations. As such, generating leverage for influence on PRC policy in other areas is a purpose for which intensified FONOP patrolling is ill-suited.

… Attempting to use FONOPs as a coercive tool would be a mistake

Finally, while this article has questioned the significance of Xi’s impact on China’s maritime policy over the first six years of his rule, his influence is likely to increase over time, pushing China’s policy in a tougher, but more coordinated direction. The significant lag between past policy decisions and their effects on the PRC’s maritime conduct—such as Jiang Zemin’s launch of the “maritime power” concept in 2000—implies that the current autocrat’s influence over particular aspects of policy in this area may accumulate and gather momentum over time.

In this regard, one of Xi’s legacies could stem from his amalgamation of China’s maritime constabulary forces. Throughout the 2000s, Chinese experts and officials identified a pressing need to unify China’s disparate maritime law enforcement fleets. In March 2013, five months into Xi’s tenure, the State Council finally announced the formation of the China Coast Guard via the merging of four maritime law enforcement agencies. The merger unsurprisingly encountered inter-agency resistance and dysfunction, but has advanced to the point where the CCG is now trusted with an increasingly powerful suite of weaponry. This presages more forceful, but also more coordinated and effective, PRC maritime dispute behavior in the future—assuming Xi remains in power.

Xi’s domestic accumulation of power has created a situation in which the functional parts of the party-state that implement front-line policy are especially keen to avoid displeasing the leader. This development carries a bifurcated logic as far as maritime assertiveness is concerned. On one hand, the nationalistic political atmosphere Xi has cultivated probably makes agencies inclined to err on the side of toughness where central policy leaves room for interpretation. At the same time, however, it also probably makes agencies more conservative in their interpretation and implementation of any instructions they are given. The likely effect of Xi’s influence over the long term, then, will be to move China’s policy in a tougher, yet also more coordinated direction.

-

Footnotes

- The PLA Navy has built up infrastructure on these reefs in successive waves of construction since it occupied them in early 1988. The wobbly-looking huts on stilts established at that time soon became fortified pillboxes; in the 1990s and 2000s these were built into solid concrete “reef fortresses” with helipads, wharves, and gun emplacements.

- China launched its first program of “regular rights defense patrols” in the East China Sea in 2006, coinciding with the unilateral development of the disputed Chunxiao gas field. In December 2008 PRC government ships made their first foray into the 12 nautical mile zone around the Diaoyu Islands, and over the following 18 months unilateral Chinese development at Chunxiao resumed despite a bilateral agreement the previous year, and Japanese officials complained of “extremely dangerous” conduct by PRC maritime law enforcement units in the disputed area.

- These have included: (a) physical exclusion of Philippine boats from Scarborough Shoal, which began in May 2012; (b) destruction of equipment and confiscation of catches of Vietnamese fishing boats in the Paracel Islands, which has been continuous since 2007 or even earlier; (c) threats against foreign firms cooperating with Vietnamese offshore energy projects within the nine-dash line, which also began in 2007; and (d) coercive “rescues” of PRC fishermen detained by Indonesia in that country’s EEZ where it overlaps with the far southern reaches of the nine-dash line, the first case of which was reported in 2010.

- Many states have established ADIZs, but China’s was abnormally broad in scope, covering all aircraft entering the zone rather than just those flying towards PRC airspace, and threatened that “China’s armed forces will adopt defensive emergency measures” against non-compliant aircraft.

Commentary

Xi Jinping and China’s maritime policy

January 22, 2019