Editor’s Note: The following article offers highlights from the 2012 European Foreign Policy Scorecard—an annual evaluation, published by the European Council on Foreign Relations, of Europe’s performance in pursuing its interests and promoting its values in the world.

Until recently, Europeans enjoyed a pretty comfortable position in most international organizations. At the IMF, they had an unquestioned hold on the directorship and could lecture other countries on how to govern themselves and run their economies, while each large European country had its own IMF representative. But all that changed in 2011. Now, Europeans are themselves being lectured by China and Brazil for not solving their financial crisis despite having the resources to do so. Europe managed to hang on to the directorship in June when Christine Lagarde succeeded Dominique Strauss-Kahn, but only because of divisions among emerging economies. If the euro crisis continues, Europeans will likely be forced to give up more of their voting weight — as they started doing in 2010 during a reallocation of IMF board seats — and ultimately lose the directorship.

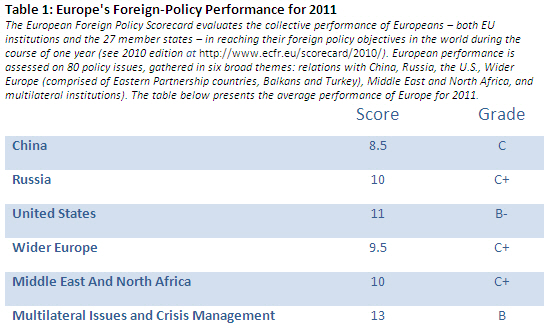

The power realignment at the IMF is just one example of the way the euro crisis has undermined Europe’s geopolitical clout in the past two years, transforming it from a reliable global problem-solver to a problem itself. True, the sky is not falling: Europe has had some remarkable successes in 2011, such as the successful intervention in Libya, the relatively smooth entry of Russia into the World Trade Organization, and the agreement reached at the Durban conference on climate change. But the out-of-control debt crisis has started eroding Europe’s foreign-policy tools and degrading its leverage with other powers like China. The 2012 edition of the European Foreign Policy Scorecard — the result of intensive research by 40 researchers under the auspices of the European Council on Foreign Relations and the Brookings Institution — makes this downward trajectory abundantly clear. If the euro crisis is not solved this year, Europe could experience in the years ahead an even more dramatic loss of power, one that would have negative consequences for world order, multilateral organizations, and the United States.

Washington may be pivoting toward Asia and casting its lot with emerging powers like India and Brazil to maintain its leadership position. But a continued erosion of Europe’s place in the world would bode ill for the Western liberal order Washington seeks to defend. For all their flaws, Europeans are still the largest contributors to international organizations and the largest purveyors of development aid, and they still outspend all the BRIC countries combined in defense expenditures. Additionally, Europe plays an important role in getting the cooperation of other powers for collective solutions favored by the United States.

Consider Europe’s soft power. Some countries are still eager to join the European Union and even adopt the euro, countries such as Iceland, Croatia, Turkey — or Poland and Hungary. But as Europe has drifted toward economic stagnation and political gridlock, the governance model for which the European Union stands — that of an expanding and ever more effective multilateralism as a solution to the problems of a globalized world — has been discredited in the eyes of many others. Advocates of regional integration projects in places such as Latin America and Southeast Asia are now less likely to look to Europe for inspiration. Last year, former Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva sounded this very alarm when he affirmed that “the world does not have the right to allow the EU to end” because “what Europeans achieved after [World War II] are part of the democratic heritage of humanity.” Unfortunately, there’s only so much the world can do. It’s up to Europeans to make the idea of Europe powerful again.

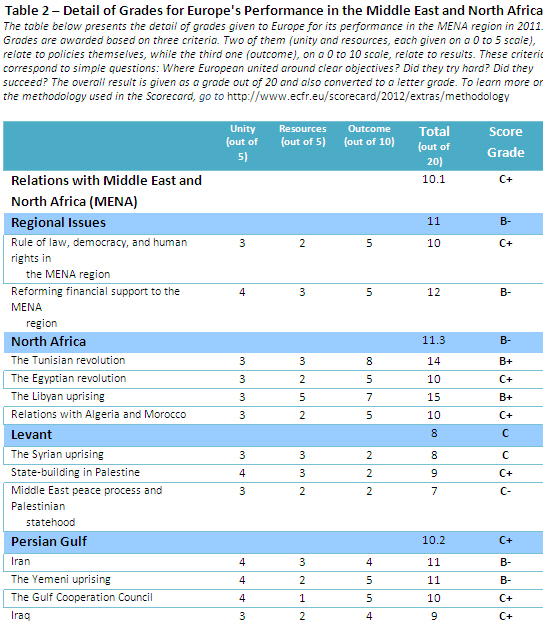

Take for example the remarkable events of the past year. The debt crisis has had a tangible impact on Europe’s ability to react to the Arab Awakening — arguably the most important geopolitical event in its neighborhood since the fall of the Berlin Wall. The revolutions in the Middle East and North Africa initially presented a challenge to European governments that, like the United States, had cozy relationships with autocratic rulers such as Tunisian President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali and Libyan leader Muammar al-Qaddafi. Europe quickly got on the right side of history, however, and agreed to a common strategy that promised the region “money, markets access, mobility.” But largely because of the financial crisis, member states have so far failed to deliver much: Budget constraints limited the money they were prepared to offer to 5.8 billion euros in direct funding; populist fears about immigration restricted offers of greater mobility for students and workers; and protectionist sentiment, fueled by economic difficulties, precluded any real opening of markets, especially to North African agricultural products. As a result, Europe is not in a position to have as much of an impact on the transformation of its southern neighborhood as it would have had a few years ago. This also means that conditionality (“more for more”) is a less potent tool of influence because the potential gains for Arab Spring countries are limited.

Beyond the Arab Awakening, the financial crisis has also undermined Europe’s embryonic attempt to develop so-called “strategic partnerships” with the world’s great powers. Realist powers such as China and Russia have long attempted to play Europeans off against each other. But in the last few years, member states had gradually begun to realize that they have a European interest in agreeing to a common position before negotiating with the Chinese or Russians. In particular, 2011 was supposed to be the year in which the European Union implemented a new approach to China based on unity and reciprocity. Rather than maintaining separate approaches to Beijing, member states were supposed to present a united front in order to increase their leverage. For example, they were aiming at opening Chinese public procurement markets (for projects like road- and dam-building) that are currently closed, while Chinese firms can bid for European markets.

Instead, Europe’s crisis turned into China’s opportunity. Cash-strapped member states sought to secure investment rather than open Chinese markets and, more importantly, independently petitioned Beijing to buy their sovereign bonds. As a result, while the European Commission made valuable efforts to open up China’s public procurement markets and ensure access to rare-earth minerals, Brussels often fought alone on these issues while member states individually sweet-talked Beijing and prioritized their bilateral ties. Europeans did have some collective successes with China — on Libya and climate change, for example — but these pale in comparison with the shift in the balance of power that took place in 2011. In late October, in between a European Council meeting and the G-20 summit he was about to host, French President Nicolas Sarkozy called his Chinese counterpart, Hu Jintao, to see whether China would contribute to an enlarged eurozone bailout fund (the answer was no). It is hard to rebalance a relationship or insist on a revaluation of the yuan when you come begging. It’s no surprise, then, that an EU-China summit and a high-level economic dialogue were canceled in November.

More generally, Europe’s deteriorating economic position has taken a toll on budgets for aid and defense, a trend that will probably continue and even intensify. Although member states such as Sweden and Britain have kept development aid at high levels, many others, including Italy and Spain, have made cuts. Meanwhile, even with the successful military intervention in Libya, Europeans are decreasing their defense budgets — by as much as one-third between 2006 and 2014, according to one estimate. This raises questions about whether Europeans will be able to maintain their role in crisis management around the world, let alone undertake serious military interventions like the one in Libya, where the difficulties of waging a modern war with limited casualties made American “leadership from behind” indispensable. Even worse, although member states discussed “pooling and sharing” military resources, in practice they cut their defense budgets and capabilities without cooperation or consultation with partners (or, for that matter, with allies in NATO), thus amplifying the effects of the cuts.

Perhaps the most insidious effect of the crisis is the way it is transforming Europe itself. In 2010, the Lisbon Treaty — which gave Europe a foreign minister and a diplomatic service for the first time — came into effect. But the financial crisis has compounded the inherent political and bureaucratic challenges of setting up these instruments. While a gradual move toward a more united European foreign policy was still conceivable in 2010, the trend whipped back toward renationalization only a year later. Just as Germany and France have often cast aside smaller member states and the European Commission and European Parliament in striking deals to resolve the euro crisis, European foreign-policymaking is increasingly dominated by what former NATO Secretary-General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer has called “selective diplomacy,” which sidelines EU institutions and smaller member states.

As a result of the euro crisis, many now perceive Germany as the unquestioned leader of Europe. In fact, some in the United States are even speculating that the answer to Henry Kissinger’s famous question about Europe’s phone number is: “Call the chancellor.” But things are not that simple. Although Germany is more powerful than ever and defers less to France and Britain on foreign policy than it used to, it is not yet ready to lead Europe — or at least not in the way that the United States would like. Germany does sometimes exert decisive leadership on foreign affairs, as it did when working with Poland to develop a coordinated European approach to Russia. But on other issues — the abstention on the Libya vote at the United Nations being the most visible in 2011 — Germany did not so much lead as use its newfound margin of maneuver to follow its own preferences, which are sometimes dictated by the needs of its export-driven economy.

France, meanwhile, reaffirmed its traditional leadership in foreign affairs with a very active year in 2011 — from the Ivory Coast to the G-20, from Libya and Syria to Iranian sanctions and the Palestinian issue — but this leadership was not always coordinated with other Europeans and sometimes undermined common objectives. For example, Paris picked various fights with Ankara, most prominently on the Armenian genocide issue, making European-Turkish cooperation more difficult. As for Britain, even before it vetoed a plan by eurozone countries in December to create a “fiscal union,” it was playing less of a leadership role than it traditionally has on key European foreign-policy issues. Furthermore, its diplomatic guerrilla campaign to block the European Union’s new diplomatic service from articulating a common EU position at the United Nations or the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe didn’t help. If Britain marginalizes itself by rejecting the leap toward integration by eurozone countries, it risks losing influence more broadly and will fade both as a necessary ingredient of Europe’s foreign policy and as a bridge with the United States.

The euro crisis thus seems to have encouraged the reassertion of national reflexes among EU countries, including the ones that matter most. The Libya operation will be remembered as a success for Europeans, but as a disaster for the European Union, which cannot exist when major powers are not aligned. A ray of hope might be coming from some smaller member states that are increasingly punching above their weight and showing leadership on specific issues. This is particularly the case with Poland and Sweden — two countries, not coincidentally, outside the eurozone that have not been badly affected by the economic crisis. Their relative success and the mediocre performance of the European Union as a whole in 2011 suggest that if Europe still hopes to retain its influence in the world in the future, it must first solve the euro crisis as a prerequisite for pursuing a coherent and effective foreign policy. Otherwise, the United States might one day confront the specter of a world without Europe — a world where its most reliable international ally is weakened, where the evolution toward competitive multipolarity is accelerated, and where the values of integration and multilateral cooperation have lost their champion.

Commentary

The Sick Man of Europe Is Europe

February 16, 2012