The long game

American order

Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from “The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order” by former Brookings Fellow Rush Doshi.

This introductory chapter summarizes the book’s argument. It explains that U.S.-China competition is over regional and global order, outlines what Chinese-led order might look like, explores why grand strategy matters and how to study it, and discusses competing views of whether China has a grand strategy. It argues that China has sought to displace America from regional and global order through three sequential “strategies of displacement” pursued at the military, political, and economic levels. The first of these strategies sought to blunt American order regionally, the second sought to build Chinese order regionally, and the third — a strategy of expansion — now seeks to do both globally. The introduction explains that shifts in China’s strategy are profoundly shaped by key events that change its perception of American power.

Introduction

It was 1872, and Li Hongzhang was writing at a time of historic upheaval. A Qing Dynasty general and official who dedicated much of his life to reforming a dying empire, Li was often compared to his contemporary Otto von Bismarck, the architect of German unification and national power whose portrait Li was said to keep for inspiration.1

Like Bismarck, Li had military experience that he parlayed into considerable influence, including over foreign and military policy. He had been instrumental in putting down the fourteen-year Taiping rebellion—the bloodiest conflict of the entire nineteenth century—which had seen a millenarian Christian state rise from the growing vacuum of Qing authority to launch a civil war that claimed tens of millions of lives. This campaign against the rebels provided Li with an appreciation for Western weapons and technology, a fear of European and Japanese predations, a commitment to Chinese self-strengthening and modernization—and critically—the influence and prestige to do something about it.

In a memorandum advocating for more investment in Chinese shipbuilding, [Li Hongzhang] penned a line since repeated for generations: China was experiencing “great changes not seen in three thousand years.”

Left: Li Hongzhang, also romanised as Li Hung-chang, in 1896. Source: Alice E. Neve Little, Li Hung-Chang: His Life and Times (London: Cassell & Company, 1903).

And so it was in 1872 that in one of his many correspondences, Li reflected on the groundbreaking geopolitical and technological transformations he had seen in his own life that posed an existential threat to the Qing. In a memorandum advocating for more investment in Chinese shipbuilding, he penned a line since repeated for generations: China was experiencing “great changes not seen in three thousand years.”2

That famous, sweeping statement is to many Chinese nationalists a reminder of the country’s own humiliation. Li ultimately failed to modernize China, lost a war to Japan, and signed the embarrassing Treaty of Shimonoseki with Tokyo. But to many, Li’s line was both prescient and accurate—China’s decline was the product of the Qing Dynasty’s inability to reckon with transformative geopolitical and technological forces that had not been seen for three thousand years, forces which changed the international balance of power and ushered in China’s “Century of Humiliation.” These were trends that all of Li’s striving could not reverse.

If Li’s line marks the highpoint of China’s humiliation, then Xi’s marks an occasion for its rejuvenation. If Li’s evokes tragedy, then Xi’s evokes opportunity.

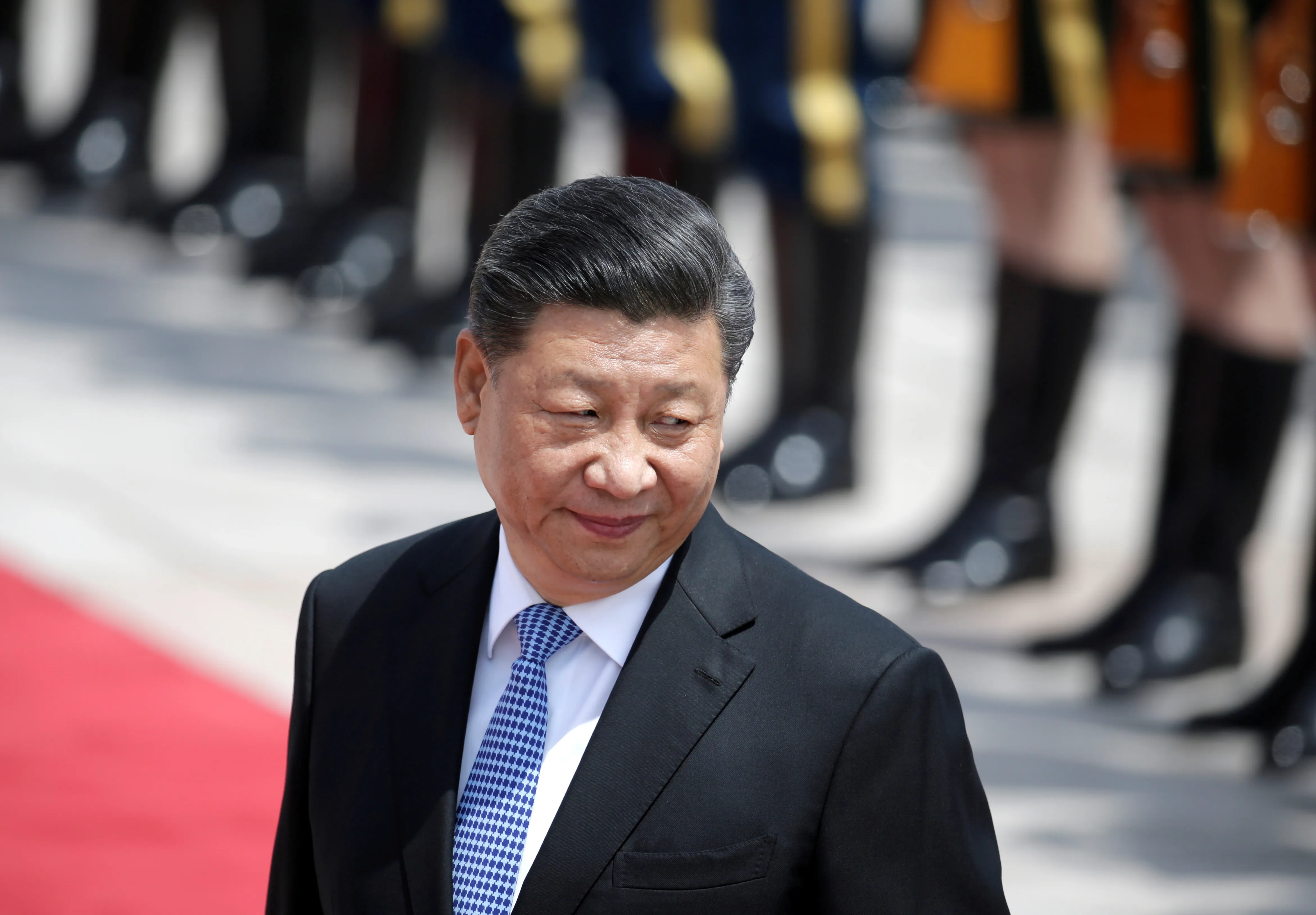

Right: Xi Jinping, president of the People’s Republic of China since 2013. Source: Reuters

Now, Li’s line has been repurposed by China’s leader Xi Jinping to inaugurate a new phase in China’s post–Cold War grand strategy. Since 2017, Xi has in many of the country’s critical foreign policy addresses declared that the world is in the midst of “great changes unseen in a century” [百年未有之大变局]. If Li’s line marks the highpoint of China’s humiliation, then Xi’s marks an occasion for its rejuvenation. If Li’s evokes tragedy, then Xi’s evokes opportunity. But both capture something essential: the idea that world order is once again at stake because of unprecedented geopolitical and technological shifts, and that this requires strategic adjustment.

For Xi, the origin of these shifts is China’s growing power and what it saw as the West’s apparent self-destruction. On June 23, 2016, the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. Then, a little more than three months later, a populist surge catapulted Donald Trump into office as president of the United States. From China’s perspective—which is highly sensitive to changes in its perceptions of American power and threat—these two events were shocking. Beijing believed that the world’s most powerful democracies were withdrawing from the international order they had helped erect abroad and were struggling to govern themselves at home. The West’s subsequent response to the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, and then the storming of the US Capitol by extremists in 2021, reinforced a sense that “time and momentum are on our side,” as Xi Jinping put it shortly after those events.3 China’s leadership and foreign policy elite declared that a “period of historical opportunity” [历史机遇期] had emerged to expand the country’s strategic focus from Asia to the wider globe and its governance systems.

We are now in the early years of what comes next—a China that not only seeks regional influence as so many great powers do, but as Evan Osnos has argued, “that is preparing to shape the twenty-first century, much as the U.S. shaped the twentieth.”4 That competition for influence will be a global one, and Beijing believes with good reason that the next decade will likely determine the outcome.

What are China’s ambitions, and does it have a grand strategy to achieve them? If it does, what is that strategy, what shapes it, and what should the United States do about it?

As we enter this new stretch of acute competition, we lack answers to critical foundational questions. What are China’s ambitions, and does it have a grand strategy to achieve them? If it does, what is that strategy, what shapes it, and what should the United States do about it? These are basic questions for American policymakers grappling with this century’s greatest geopolitical challenge, not least because knowing an opponent’s strategy is the first step to countering it. And yet, as great power tensions flare, there is no consensus on the answers.

This book attempts to provide an answer. In its argument and structure, the book takes its inspiration in part from Cold War studies of US grand strategy.5 Where those works analyzed the theory and practice of US “strategies of containment” toward the Soviet Union during the Cold War, this book seeks to analyze the theory and practice of China’s “strategies of displacement” toward the United States after the Cold War.

To do so, the book makes use of an original database of Chinese Communist Party documents—memoirs, biographies, and daily records of senior officials—painstakingly gathered and then digitized over the last several years from libraries, bookstores in Taiwan and Hong Kong, and Chinese e-commerce sites (see Appendix). Many of the documents take readers behind the closed doors of the Chinese Communist Party, bring them into its high-level foreign policy institutions and meetings, and introduce readers to a wide cast of Chinese political leaders, generals, and diplomats charged with devising and implementing China’s grand strategy. While no one master document contains all of Chinese grand strategy, its outline can be found across a wide corpus of texts. Within them, the Party uses hierarchical statements that represent internal consensus on key issues to guide the ship of state, and these statements can be traced across time. The most important of these is the Party line (路线), then the guideline (方针), and finally the policy (政策), among other terms. Understanding them sometimes requires proficiency not only in Chinese, but also in seemingly impenetrable and archaic ideological concepts like “dialectical unities” and “historical materialism.”

Argument in Brief

The book argues that the core of US-China competition since the Cold War has been over regional and now global order. It focuses on the strategies that rising powers like China use to displace an established hegemon like the United States short of war. A hegemon’s position in regional and global order emerges from three broad “forms of control” that are used to regulate the behavior of other states: coercive capability (to force compliance), consensual inducements (to incentivize it), and legitimacy (to rightfully command it). For rising states, the act of peacefully displacing the hegemon consists of two broad strategies generally pursued in sequence. The first strategy is to blunt the hegemon’s exercise of those forms of control, particularly those extended over the rising state; after all, no rising state can displace the hegemon if it remains at the hegemon’s mercy. The second is to build forms of control over others; indeed, no rising state can become a hegemon if it cannot secure the deference of other states through coercive threats, consensual inducements, or rightful legitimacy. Unless a rising power has first blunted the hegemon, efforts to build order are likely to be futile and easily opposed. And until a rising power has successfully conducted a good degree of blunting and building in its home region, it remains too vulnerable to the hegemon’s influence to confidently turn to a third strategy, global expansion, which pursues both blunting and building at the global level to displace the hegemon from international leadership. Together, these strategies at the regional and then global levels provide a rough means of ascent for the Chinese Communist Party’s nationalist elites, who seek to restore China to its due place and roll back the historical aberration of the West’s overwhelming global influence.

This is a template China has followed, and in its review of China’s strategies of displacement, the book argues that shifts from one strategy to the next have been triggered by sharp discontinuities in the most important variable shaping Chinese grand strategy: its perception of US power and threat. China’s first strategy of displacement (1989–2008) was to quietly blunt American power over China, particularly in Asia, and it emerged after the traumatic trifecta of Tiananmen Square, the Gulf War, and the Soviet collapse led Beijing to sharply increase its perception of US threat. China’s second strategy of displacement (2008–2016) sought to build the foundation for regional hegemony in Asia, and it was launched after the Global Financial Crisis led Beijing to see US power as diminished and emboldened it to take a more confident approach. Now, with the invocation of “great changes unseen in a century” following Brexit, President Trump’s election, and the coronavirus pandemic, China is launching a third strategy of displacement, one that expands its blunting and building efforts worldwide to displace the United States as the global leader. In its final chapters, this book uses insights about China’s strategy to formulate an asymmetric US grand strategy in response—one that takes a page from China’s own book—and would seek to contest China’s regional and global ambitions without competing dollar-for-dollar, ship-for-ship, or loan-for-loan.

Order abroad is often a reflection of order at home, and China’s order-building would be distinctly illiberal relative to US order-building.

The book also illustrates what Chinese order might look like if China is able to achieve its goal of “national rejuvenation” by the centennial of the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 2049. At the regional level, China already accounts for more than half of Asian GDP and half of all Asian military spending, which is pushing the region out of balance and toward a Chinese sphere of influence. A fully realized Chinese order might eventually involve the withdrawal of US forces from Japan and Korea, the end of American regional alliances, the effective removal of the US Navy from the Western Pacific, deference from China’s regional neighbors, unification with Taiwan, and the resolution of territorial disputes in the East and South China Seas. Chinese order would likely be more coercive than the present order, consensual in ways that primarily benefit connected elites even at the expense of voting publics, and considered legitimate mostly to those few who it directly rewards. China would deploy this order in ways that damage liberal values, with authoritarian winds blowing stronger across the region. Order abroad is often a reflection of order at home, and China’s order-building would be distinctly illiberal relative to US order-building.

At the global level, Chinese order would involve seizing the opportunities of the “great changes unseen in a century” and displacing the United States as the world’s leading state. This would require successfully managing the principal risk flowing from the “great changes”—Washington’s unwillingness to gracefully accept decline—by weakening the forms of control supporting American global order while strengthening those forms of control supporting a Chinese alternative. That order would span a “zone of super-ordinate influence” in Asia as well as “partial hegemony” in swaths of the developing world that might gradually expand to encompass the world’s industrialized centers—a vision some Chinese popular writers describe using Mao’s revolutionary guidance to “surround the cities from the countryside” [农村包围城市].6 More authoritative sources put this approach in less sweeping terms, suggesting Chinese order would be anchored in China’s Belt and Road Initiative and its Community of Common Destiny, with the former in particular creating networks of coercive capability, consensual inducement, and legitimacy.7

The “struggle for mastery,” once confined to Asia, is now over the global order and its future. If there are two paths to hegemony—a regional one and a global one—China is now pursuing both.

Some of the strategy to achieve this global order is already discernable in Xi’s speeches. Politically, Beijing would project leadership over global governance and international institutions, split Western alliances, and advance autocratic norms at the expense of liberal ones. Economically, it would weaken the financial advantages that underwrite US hegemony and seize the commanding heights of the “fourth industrial revolution” from artificial intelligence to quantum computing, with the United States declining into a “deindustrialized, English-speaking version of a Latin American republic, specializing in commodities, real estate, tourism, and perhaps transnational tax evasion.”8 Militarily, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) would field a world-class force with bases around the world that could defend China’s interests in most regions and even in new domains like space, the poles, and the deep sea. The fact that aspects of this vision are visible in high-level speeches is strong evidence that China’s ambitions are not limited to Taiwan or to dominating the Indo-Pacific. The “struggle for mastery,” once confined to Asia, is now over the global order and its future. If there are two paths to hegemony—a regional one and a global one—China is now pursuing both.

This glimpse at possible Chinese order maybe striking, but it should not be surprising. Over a decade ago, Lee Kuan Yew—the visionary politician who built modern Singapore and personally knew China’s top leaders—was asked by an interviewer, “Are Chinese leaders serious about displacing the United States as the number one power in Asia and in the world?” He answered with an emphatic yes. “Of course. Why not?” he began, “They have transformed a poor society by an economic miracle to become now the second-largest economy in the world—on track . . . to become the world’s largest economy.” China, he continued, boasts “a culture 4,000 years old with 1.3 billion people, with a huge and very talented pool to draw from. How could they not aspire to be number one in Asia, and in time the world?” China was “growing at rates unimaginable 50 years ago, a dramatic transformation no one predicted,” he observed, and “every Chinese wants a strong and rich China, a nation as prosperous, advanced, and technologically competent as America, Europe, and Japan.” He closed his answer with a key insight: “This reawakened sense of destiny is an overpowering force. . . . China wants to be China and accepted as such, not as an honorary member of the West.” China might want to “share this century” with the United States, perhaps as “co-equals,” he noted, but certainly not as subordinates.9

Why Grand Strategy Matters

The need for a grounded understanding of China’s intentions and strategy has never been more urgent. China now poses a challenge unlike any the United States has ever faced. For more than a century, no US adversary or coalition of adversaries has reached 60 percent of US GDP. Neither Wilhelmine Germany during the First World War, the combined might of Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany during the Second World War, nor the Soviet Union at the height of its economic power ever crossed this threshold.10 And yet, this is a milestone that China itself quietly reached as early as 2014. When one adjusts for the relative price of goods, China’s economy is already 25 percent larger than the US economy.11 It is clear, then, that China is the most significant competitor that the United States has faced and that the way Washington handles its emergence to superpower status will shape the course of the next century.

What makes grand strategy “grand” is not simply the size of the strategic objectives but also the fact that disparate “means” are coordinated together to achieve it.

What is less clear, at least in Washington, is whether China has a grand strategy and what it might be. This book defines grand strategy as a state’s theory of how it can achieve its strategic objectives that is intentional, coordinated, and implemented across multiple means of statecraft—military, economic, and political. What makes grand strategy “grand” is not simply the size of the strategic objectives but also the fact that disparate “means” are coordinated together to achieve it. That kind of coordination is rare, and most great powers consequently do not have a grand strategy.

When states do have grand strategies, however, they can reshape world history. Nazi Germany wielded a grand strategy that used economic tools to constrain its neighbors, military buildups to intimidate its rivals, and political alignments to encircle its adversaries—allowing it to outperform its great power competitors for a considerable time even though its GDP was less than one-third theirs. During the Cold War, Washington pursued a grand strategy that at times used military power to deter Soviet aggression, economic aid to curtail communist influence, and political institutions to bind liberal states together—limiting Soviet influence without a US-Soviet war. How China similarly integrates its instruments of statecraft in pursuit of overarching regional and global objectives remains an area that has received abundant speculation but little rigorous study despite its enormous consequences. The coordination and long-term planning involved in grand strategy allow a state to punch above its weight; since China is already a heavyweight, if it has a coherent scheme that coordinates its $14 trillion economy with its blue-water navy and rising political influence around the world—and the United States either misses it or misunderstands it—the course of the twenty-first century may unfold in ways detrimental to the United States and the liberal values it has long championed.

Washington is belatedly coming to terms with this reality, and the result is the most consequential reassessment of its China policy in over a generation. And yet, amid this reassessment, there is wide-ranging disagreement over what China wants and where it is going. Some believe Beijing has global ambitions; others argue that its focus is largely regional. Some claim it has a coordinated 100-year plan; others that it is opportunistic and error-prone. Some label Beijing a boldly revisionist power; others see it as a sober-minded stakeholder of the current order. Some say Beijing wants the United States out of Asia; and others that it tolerates a modest US role. Where analysts increasingly agree is on the idea that China’s recent assertiveness is a product of Chinese President Xi’s personality—a mistaken notion that ignores the long-standing Party consensus in which China’s behavior is actually rooted. The fact that the contemporary debate remains divided on so many fundamental questions related to China’s grand strategy—and inaccurate even in its major areas of agreement—is troubling, especially since each question holds wildly different policy implications.

The Unsettled Debate

This book enters a largely unresolved debate over Chinese strategy divided between “skeptics” and “believers.” The skeptics have not yet been persuaded that China has a grand strategy to displace the United States regionally or globally; by contrast, the believers have not truly attempted persuasion.

The skeptics are a wide-ranging and deeply knowledgeable group. “China has yet to formulate a true ‘grand strategy,’” notes one member, “and the question is whether it wants to do so at all.”12 Others have argued that China’s goals are “inchoate” and that Beijing lacks a “well-defined” strategy.13 Chinese authors like Professor Wang Jisi, former dean of Peking University’s School of International Relations, are also in the skeptical camp. “There is no strategy that we could come up with by racking our brains that would be able to cover all the aspects of our national interests,” he notes.14

Other skeptics believe that China’s aims are limited, arguing that China does not wish to displace the United States regionally or globally and remains focused primarily on development and domestic stability. One deeply experienced White House official was not yet convinced of “Xi’s desire to throw the United States out of Asia and destroy U.S. regional alliances.”15 Other prominent scholars put the point more forcefully: “[One] hugely distorted notion is the now all-too-common assumption that China seeks to eject the United States from Asia and subjugate the region. In fact, no conclusive evidence exists of such Chinese goals.”16

In contrast to these skeptics are the believers. This group is persuaded that China has a grand strategy to displace the United States regionally and globally, but it has not put forward a work to persuade the skeptics. Within government, some top intelligence officials—including former director of national intelligence Dan Coates—have stated publicly that “the Chinese fundamentally seek to replace the United States as the leading power in the world” but have not (or perhaps could not) elaborate further, nor did they suggest that this goal was accompanied by a specific strategy.17

Outside of government, only a few recent works attempt to make the case at length. The most famous is Pentagon official Michael Pillsbury’s bestselling One Hundred Year Marathon, though it argues somewhat overstatedly that China has had a secret grand plan for global hegemony since 1949 and, in key places, relies heavily on personal authority and anecdote.18 Many other books come to similar conclusions and get much right, but they are more intuitive than rigorously empirical and could have been more persuasive with a social scientific approach and a richer evidentiary base.19 A handful of works on Chinese grand strategy take a broader perspective emphasizing the distant past or future, but they therefore dedicate less time to the critical stretch from the post–Cold War era to the present that is the locus of US-China competition.20 Finally, some works mix a more empirical approach with careful and precise arguments about China’s contemporary grand strategy. These works form the foundation for this book’s approach.21

This book, which draws on the research of so many others, also hopes to stand apart in key ways. These include a unique social-scientific approach to defining and studying grand strategy; a large trove of rarely cited or previously inaccessible Chinese texts; a systematic study of key puzzles in Chinese military, political, and economic behavior; and a close look at the variables shaping strategic adjustment. Taken together, it is hoped that the book makes a contribution to the emerging China debate with a unique method for systematically and rigorously uncovering China’s grand strategy.

Uncovering Grand Strategy

The challenge of deciphering a rival’s grand strategy from its disparate behavior is not a new one. In the years before the First World War, the British diplomat Eyre Crowe wrote an important 20,000-word “Memorandum on the Present State of British Relations with France and Germany” that attempted to explain the wide-ranging behavior of a rising Germany.22 Crowe was a keen observer of Anglo-German relations with a passion and perspective for the subject informed by his own heritage. Born in Leipzig and educated in Berlin and Düsseldorf, Crowe was half German, spoke German-accented English, and joined the British Foreign Office at the age of twenty-one. During World War I, his British and German families were literally at war with one another—his British nephew perished at sea while his German cousin rose to become chief of the German Naval Staff.

Crowe argued in his framing of the enterprise, “the choice must lie between . . . two hypotheses”—each of which resemble the positions of today’s skeptics and believers with respect to China’s grand strategy.

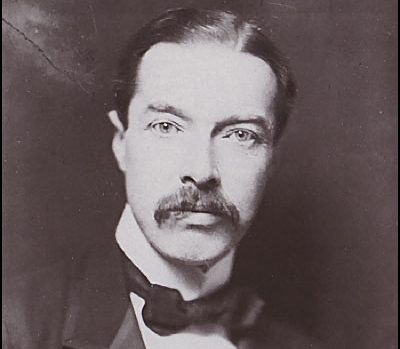

Left: British diplomat Eyre Crowe (1864-1925). Date unknown. Author unknown. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Crowe, who wrote his memorandum in 1907, sought to systematically analyze the disparate, complex, and seemingly uncoordinated range of German foreign behavior, to determine whether Berlin had a “grand design” that ran through it, and to report to his superiors what it might be. In order to “formulate and accept a theory that will fit all the ascertained facts of German foreign policy,” Crowe argued in his framing of the enterprise, “the choice must lie between . . . two hypotheses”—each of which resemble the positions of today’s skeptics and believers with respect to China’s grand strategy.23

Crowe’s first hypothesis was that Germany had no grand strategy, only what he called a “vague, confused, and unpractical statesmanship.” In this view, Crowe wrote, it is possible that “Germany does not really know what she is driving at, and that all her excursions and alarums, all her underhand intrigues do not contribute to the steady working out of a well conceived and relentlessly followed system of policy.”24 Today, this argument mirrors those of skeptics who claim China’s bureaucratic politics, factional infighting, economic priorities, and nationalist knee-jerk reactions all conspire to thwart Beijing from formulating or executing an overarching strategy.24

Crowe’s second hypothesis was that important elements of German behavior were coordinated together through a grand strategy “consciously aiming at the establishment of a German hegemony, at first in Europe, and eventually in the world.”26 Crowe ultimately endorsed a more cautious version of this hypothesis, and he concluded that German strategy was “deeply rooted in the relative position of the two countries,” with Berlin dissatisfied by the prospect of remaining subordinate to London in perpetuity.26 This argument mirrors the position of believers in Chinese grand strategy. It also resembles the argument of this book: China has pursued a variety of strategies to displace the United States at the regional and global level which are fundamentally driven by its relative position with Washington.

The fact that the questions the Crowe memorandum explored have a striking similarity to those we are grappling with today has not been lost on US officials. Henry Kissinger quotes from it in On China. Max Baucus, former US ambassador to China, frequently mentioned the memo to his Chinese interlocutors as a roundabout way of inquiring about Chinese strategy.28

Crowe’s memorandum has a mixed legacy, with contemporary assessments split over whether he was right about Germany. Nevertheless, the task Crowe set remains critical and no less difficult today, particularly because China is a “hard target” for information collection. One might hope to improve on Crowe’s method with a more rigorous and falsifiable approach anchored in social science. As the next chapter discusses in detail, this book argues that to identify the existence, content, and adjustment of China’s grand strategy, researchers must find evidence of (1) grand strategic concepts in authoritative texts; (2) grand strategic capabilities in national security institutions; and (3) grand strategic conduct in state behavior. Without such an approach, any analysis is more likely to fall victim to the kinds of natural biases in “perception and misperception” that often recur in assessments of other powers.29

Chapter Summaries

This book argues that, since the end of the Cold War, China has pursued a grand strategy to displace American order first at the regional and now at the global level.

Chapter 1 defines grand strategy and international order, and then explores how rising powers displace hegemonic order through strategies of blunting, building, and expansion. It explains how perceptions of the established hegemon’s power and threat shape the selection of rising power grand strategies.

Chapter 2 focuses on the Chinese Communist Party as the connective institutional tissue for China’s grand strategy. As a nationalist institution that emerged from the patriotic ferment of the late Qing period, the Party now seeks to restore China to its rightful place in the global hierarchy by 2049. As a Leninist institution with a centralized structure, ruthless amorality, and a Leninist vanguard seeing itself as stewarding a nationalist project, the Party possesses the “grand strategic capability” to coordinate multiple instruments of statecraft while pursuing national interests over parochial ones. Together, the Party’s nationalist orientation helps set the ends of Chinese grand strategy while Leninism provides an instrument for realizing them. Now, as China rises, the same Party that sat uneasily within Soviet order during the Cold War is unlikely to permanently tolerate a subordinate role in American order. Finally, the chapter focuses on the Party as a subject of research, noting how a careful review of the Party’s voluminous publications can provide insight into its grand strategic concepts.

Part I begins with Chapter 3, which explores the blunting phase of China’s post–Cold War grand strategy using Chinese Communist Party texts. It demonstrates that China went from seeing the United States as a quasi-ally against the Soviets to seeing it as China’s greatest threat and “main adversary” in the wake of three events: the traumatic trifecta of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, the Gulf War, and the Soviet Collapse. In response, Beijing launched its blunting strategy under the Party guideline of “hiding capabilities and biding time.” This strategy was instrumental and tactical. Party leaders explicitly tied the guideline to perceptions of US power captured in phrases like the “international balance of forces” and “multipolarity,” and they sought to quietly and asymmetrically weaken American power in Asia across military, economic, and political instruments, each of which is considered in the subsequent three book chapters.

Chapter 4 considers blunting at the military level. It shows that the trifecta prompted China to depart from a “sea control” strategy increasingly focused on holding distant maritime territory to a “sea denial” strategy focused on preventing the US military from traversing, controlling, or intervening in the waters near China. That shift was challenging, so Beijing declared it would “catch up in some areas and not others” and vowed to build “whatever the enemy fears” to accomplish it—ultimately delaying the acquisition of costly and vulnerable vessels like aircraft carriers and instead investing in cheaper asymmetric denial weapons. Beijing then built the world’s largest mine arsenal, the world’s first anti-ship ballistic missile, and the world’s largest submarine fleet—all to undermine US military power.

Chapter 5 considers blunting at the political level. It demonstrates that the trifecta led China to reverse its previous opposition to joining regional institutions. Beijing feared that multilateral organizations like Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Regional Forum (ARF) might be used by Washington to build a liberal regional order or even an Asian NATO, so China joined them to blunt American power. It stalled institutional progress, wielded institutional rules to constrain US freedom of maneuver, and hoped participation would reassure wary neighbors otherwise tempted to join a US-led balancing coalition.

Chapter 6 considers blunting at the economic level. It argues that the trifecta laid bare China’s dependence on the US market, capital, and technology—notably through Washington’s post-Tiananmen sanctions and its threats to revoke most-favored-nation (MFN) trade status, which could have seriously damaged China’s economy. Beijing sought not to decouple from the United States but instead to bind the discretionary use of American economic power, and it worked hard to remove MFN from congressional review through “permanent normal trading relations,” leveraging negotiations in APEC and the World Trade Organization (WTO) to obtain it.

Because Party leaders explicitly tied blunting to assessments of American power, that meant that when those perceptions changed, so too did China’s grand strategy. Part II of the book explores this second phase in Chinese grand strategy, which was focused on building regional order. The strategy took place under a modification to Deng’s guidance to “hide capabilities and bide time,” one that instead emphasized “actively accomplishing something.”

Chapter 7 explores this building strategy in Party texts, demonstrating that the shock of the Global Financial Crisis led China to see the United States as weakening and emboldened it to shift to a building strategy. It begins with a thorough review of China’s discourse on “multipolarity” and the “international balance of forces.” It then shows that the Party sought to lay the foundations for order—coercive capacity, consensual bargains, and legitimacy—under the auspices of the revised guidance “actively accomplish something” [积极有所作为] issued by Chinese leader Hu Jintao. This strategy, like blunting before it, was implemented across multiple instruments of statecraft—military, political, and economic—each of which receives a chapter.

Chapter 8 focuses on building at the military level, recounting how the Global Financial Crisis accelerated a shift in Chinese military strategy away from a singular focus on blunting American power through sea denial to a new focus on building order through sea control. China now sought the capability to hold distant islands, safeguard sea lines, intervene in neighboring countries, and provide public security goods. For these objectives, China needed a different force structure, one that it had previously postponed for fear that it would be vulnerable to the United States and unsettle China’s neighbors. These were risks a more confident Beijing was now willing to accept. China promptly stepped up investments in aircraft carriers, capable surface vessels, amphibious warfare, marines, and overseas bases.

Chapter 9 focuses on building at the political level. It shows how the Global Financial Crisis caused China to depart from a blunting strategy focused on joining and stalling regional organizations to a building strategy that involved launching its own institutions. China spearheaded the launch of the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the elevation and institutionalization of the previously obscure Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia (CICA). It then used these institutions, with mixed success, as instruments to shape regional order in the economic and security domains in directions it preferred.

Chapter 10 focuses on building at the economic level. It argues that the Global Financial Crisis helped Beijing depart from a defensive blunting strategy that targeted American economic leverage to an offensive building strategy designed to build China’s own coercive and consensual economic capacities. At the core of this effort were China’s Belt and Road Initiative, its robust use of economic statecraft against its neighbors, and its attempts to gain greater financial influence.

Beijing used these blunting and building strategies to constrain US influence within Asia and to build the foundations for regional hegemony. The relative success of that strategy was remarkable, but Beijing’s ambitions were not limited only to the Indo-Pacific. When Washington was again seen as stumbling, China’s grand strategy evolved—this time in a more global direction. Accordingly, Part III of this book focuses on China’s third grand strategy of displacement, global expansion, which sought to blunt but especially build global order and to displace the United States from its leadership position.

Chapter 11 discusses the dawn of China’s expansion strategy. It argues that the strategy emerged following another trifecta, this time consisting of Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and the West’s poor initial response to the coronavirus pandemic. In this period, the Chinese Communist Party reached a paradoxical consensus: it concluded that the United States was in retreat globally but at the same time was waking up to the China challenge bilaterally. In Beijing’s mind, “great changes unseen in a century” were underway, and they provided an opportunity to displace the United States as the leading global state by 2049, with the next decade deemed the most critical to this objective.

Chapter 12 discusses the “ways and means” of China’s strategy of expansion. It shows that politically, Beijing would seek to project leadership over global governance and international institutions and to advance autocratic norms. Economically, it would weaken the financial advantages that underwrite US hegemony and seize the commanding heights of the “fourth industrial revolution.” And militarily, the PLA would field a truly global Chinese military with overseas bases around the world.

Chapter 13, the book’s final chapter, outlines a US response to China’s ambitions for displacing the United States from regional and global order. It critiques those who advocate a counterproductive strategy of confrontation or an accommodationist one of grand bargains, each of which respectively discounts US domestic headwinds and China’s strategic ambitions. The chapter instead argues for an asymmetric competitive strategy, one that does not require matching China dollar-for-dollar, ship-for-ship, or loan-for-loan.

This cost-effective approach emphasizes denying China hegemony in its home region and—taking a page from elements of China’s own blunting strategy—focuses on undermining Chinese efforts in Asia and worldwide in ways that are of lower cost than Beijing’s efforts to build hegemony. At the same time, this chapter argues that the United States should pursue order-building as well, reinvesting in the very same foundations of American global order that Beijing presently seeks to weaken. This discussion seeks to convince policymakers that even as the United States faces challenges at home and abroad, it can still secure its interests and resist the spread of an illiberal sphere of influence—but only if it recognizes that the key to defeating an opponent’s strategy is first to understand it.

Endnotes

- 1. Harold James, Krupp: A History of the Legendary British Firm (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012), 51.

- 2. For this memo, see Li Hongzhang [李鸿章], “Memo on Not Abandoning the Manufacture of Ships” [筹议制造轮船未可裁撤折], in The Complete Works of Li Wenzhong [李文忠公全集], vol. 19, 1872, 45. Li Hongzhang was also called Li Wenzhong.

- 3. Xi Jinping [习近平], “Xi Jinping Delivered an Important Speech at the Opening Ceremony of the Seminar on Learning and Implementing the Spirit of the Fifth Plenary Session of the 19th Central Committee of the Party” [习近平在省部级主要领导干部学习贯彻党的十九届五中全会精神专题研讨班开班式上发表重要讲话], Xinhua [新华], January 11, 2021.

- 4. Evan Osnos, “The Future of America’s Contest with China,” The New Yorker, January 13, 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/01/13/the-future-of-americas-contest-with-china.

- 5. For example, John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of American National Security Policy during the Cold War (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2005).

- 6. Robert E. Kelly, “What Would Chinese Hegemony Look Like?,” The Diplomat, February 10, 2014, https://thediplomat.com/2014/02/what-would-chinese-hegemony-look-like/; Nadège Rolland, “China’s Vision for a New World Order” (Washington, DC: The National Bureau of Asian Research, 2020), https://www.nbr.org/publication/chinas-vision-for-a-new-world-order/.

- 7. See Yuan Peng [袁鹏], “The Coronavirus Pandemic and the Great Changes Unseen in a Century,” [新冠疫情与百年变局], Contemporary International Relations [现代国际关系], no. 5 (June 2020): 1–6, by the head of the leading Ministry of State Security think tank.

- 8. Michael Lind, “The China Question,” Tablet, May 19, 2020, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news/articles/china-strategy-trade-lind.

- 9. Graham Allison and Robert Blackwill, “Interview: Lee Kuan Yew on the Future of U.S.-China Relations,” The Atlantic, March 5, 2013, https://www.theatlantic.com/china/archive/2013/03/interview-lee-kuan-yew-on-the-future-of-us-china-relations/273657/.

- 10. Andrew F. Krepinevich, “Preserving the Balance: A U.S. Eurasia Defense Strategy” (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, January 19, 2017), https://csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/Preserving_the_Balance_%2819Jan17%29HANDOUTS.pdf.

- 11. “GDP, (US$),” World Bank, 2019, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ny.gdp.mktp.cd.

- 12. Angela Stanzel, Jabin Jacob, Melanie Hart, and Nadège Rolland, “Grand Designs: Does China Have a ‘Grand Strategy’” (European Council on Foreign Relations, October 18, 2017), https://ecfr.eu/publication/grands_designs_does_china_have_a_grand_strategy/#.

- 13. Susan Shirk, “Course Correction: Toward an Effective and Sustainable China Policy” (remarks, National Press Club, Washington, DC, February 12, 2019), https://asiasociety.org/center-us-china-relations/events/course-correction-toward-effective-and-sustainable-china-policy.

- 14. Quoted in Robert Sutter, Chinese Foreign Relations: Power and Policy since the Cold War, 3rd ed. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012), 9–10. See also Wang Jisi, “China’s Search for a Grand Strategy: A Rising Great Power Finds Its Way,” Foreign Affairs 90, no. 2 (2011): 68–79, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2011-02-20/chinas-search-grand-strategy.

- 15. Jeffrey A. Bader, “How Xi Jinping Sees the World, and Why” (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 2016), http://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/xi_jinping_worldview_bader-1.pdf.

- 16. Michael Swaine, “The U.S. Can’t Afford to Demonize China,” Foreign Policy, June 29, 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/06/29/the-u-s-cant-afford-to-demonize-china/.

- 17. Jamie Tarabay, “CIA Official: China Wants to Replace US as World Superpower,” CNN, July 21, 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/07/20/politics/china-cold-war-us-superpower-influence/index.html. Daniel Coats, “Annual Threat Assessment,” (testimony, January 29, 2019), https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/Newsroom/Testimonies/2019-01-29-ATA-Opening-Statement_Final.pdf.

- 18. Alastair Iain Johnston, “Shaky Foundations: The ‘Intellectual Architecture’ of Trump’s China Policy,” Survival 61, no. 2 (2019): 189–202, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2019.1589096; Jude Blanchette, “The Devil Is in the Footnotes: On Reading Michael Pillsbury’s The Hundred-Year Marathon” (La Jolla, CA: UC San Diego 21st Century China Program, 2018), https://china.ucsd.edu/_files/The-Hundred-Year-Marathon.pdf.

- 19. Jonathan Ward, China’s Vision of Victory (Washington, DC: Atlas Publishing and Media Company, 2019); Martin Jacques, When China Rules the World: The Rise of the Middle Kingdom and the End of the Western World (New York: Penguin, 2012).

- 20. Sulmaan Wasif Khan, Haunted by Chaos: China’s Grand Strategy from Mao Zedong to Xi Jinping (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018); Andrew Scobell, Edmund J. Burke, Cortez A. Cooper III, Sale Lilly, Chad J. R. Ohlandt, Eric Warner, J.D. Williams, China’s Grand Strategy Trends, Trajectories, and Long-Term Competition (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2020), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2798.html.

- 21. See Avery Goldstein, Rising to the Challenge China’s Grand Strategy and International Security (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005); Aaron L. Friedberg, A Contest for Supremacy: China, America, and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012); David Shambaugh, China Goes Global: The Partial Power (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2013); Ashley J. Tellis, “Pursuing Global Reach: China’s Not So Long March toward Preeminence,” in Strategic Asia 2019: China’s Expanding Strategic Ambitions, eds. Ashley J. Tellis, Alison Szalwinski, and Michael Wills (Washington, DC: National Bureau of Asian Research, 2019), 3–46, https://www.nbr.org/publication/strategic-asia-2019-chinas-expanding-strategic-ambitions/.

- 22. For the full text, as well as the responses to it within the British Foreign Office, see Eyre Crowe, “Memorandum on the Present State of British Relations with France and Germany,” in British Documents on the Origins of the War, 1898–1914, eds. G. P. Gooch and Harold Temperley (London: His Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1926), 397–420.

- 23. Ibid., 417.

- 24. Ibid., 415.

- 25. Ibid., 415.

- 26. Ibid., 414.

- 27. Ibid., 414.

- 28. Interview.

- 29. Robert Jervis, Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976).

Acknowledgments

Web design: Rachel Slattery