Shanghai’s dynamic art scene

Editor’s Note: The following is an adapted excerpt from Cheng Li’s forthcoming book, “Middle Class Shanghai: Reshaping U.S.-China Engagement” (May 11, 2021). All photos in this piece, except if otherwise identified, were taken by the author in September and December 2019.

Among the many forces shaping China’s domestic transformation and its role on the world stage, none may prove more significant than the rapid emergence and explosive growth of the Chinese middle class. At the center of this story in China is the city of Shanghai.

Any comprehensive study of the middle class in Shanghai must include an exploration of the cultural discourse and dynamic activity of its artistic community. Shanghai historically has been a cradle for Chinese contemporary art, and the city’s art scene has enjoyed longstanding exposure to Western culture.

This does not just stem from Shanghai’s colonial legacy or the interaction and influence of the throngs of foreign visitors to the city; it also relates to the large proportion of students from Shanghai who have studied Western and foreign art abroad. Artists from Shanghai were among the first group of Chinese students to study abroad in the 1980s, and most of them later returned to live and work in Shanghai.

Since 1996, artists in China and overseas have jointly organized the Shanghai Biennale, a biannual art exhibition, in an effort to establish more professional ties, both with the international art world and with audiences in China. The Biennale normalizes experimental art and creates a legitimate space for exhibiting controversial art forms — including works that challenge social and political norms.

Left: The Power Station of Art (PSA), completed in 2012 in the West Bund, has served as the venue for the Shanghai Biennale ever since. Like the Tate Modern in London, the PSA resides in a converted power plant, which serves as the eponym of the museum. Right: The 12th Shanghai Biennale, held from 2018 to 2019, was noted for its ingenious and thought-provoking thematic title in both English and Chinese. The English title was “Proregress,” a word coined by the late American poet E. E. Cummings, which condensed “progress” and “regress.” “Proregress” reflected the profound contradictions that plague both the imperative for transformation and the barriers of stagnation in the contemporary world. The Chinese thematic title of the Biennale employed the rarely used term “yubu,” which refers to the mystical Daoist ritual dance of ancient China in which the dancer appears to be moving forward while simultaneously going backward, or vice versa.

The establishment of the Shanghai Biennale has heralded a southward shift, and dynamism in modern Chinese art is increasingly moving from Beijing to Shanghai and other southeastern coastal areas. Shanghai has made a concerted effort to promote contemporary art — especially avant-garde work — to prominence in the public arena. According to one recent study, over the past decade, Shanghai has hosted an average of 300 international exhibitions every year, a significant portion of which are focused on art and culture.

Chinese contemporary art, or more precisely, Chinese avant-garde art, was not born in Shanghai, but manifested in Beijing in 1979, when a small group of artists organized an unofficial exhibition on the park railings directly opposite the National Art Museum of China. Although this avant-garde exhibition lasted only two days before being shut down by government authorities, the Chinese avant-garde movement continued to grow in the capital before eventually settling in the 798 Art District in northeast Beijing during the early 2000s.

Around the same time, a group of mainly Chinese but also foreign artists and curators in Shanghai took over the abandoned warehouses of a former textile mill, as well as factories on Moganshan Road, now known as M50 Creative Park, and other nearby areas. As of 2021, there are still over 100 studios and exhibitions by the community of avant-garde artists in this area.

Left: A poster for the new exhibition on the wall outside an art gallery in M50 Creative Park. Right: An avant-garde piece exhibited at an art gallery in M50 Creative Park in 2019. No one could have imagined this image would become an everyday scene around the world in the following years.

In addition, an enormous compound of buildings has been under construction just outside M50, which will serve as a new art center in the district.

In recent years, Shanghai has experienced an exponentially rapid expansion of art galleries. In 2001, a local Shanghai English-language magazine identified just 47 galleries in the city that were reasonably well established. However, by 2019, according to a ranking by the World Cities Culture Forum, Shanghai was ranked third in the world in terms of total number of art galleries (770), behind only New York (1,475) and Paris (1,142), and ahead of Tokyo (618), London (478), Rome (355), Brussels (313), and Los Angeles (279).

The Shanghai municipal government has recognized the need to establish excellent museums as the city’s landmarks, recently designating the 8.4-mile stretch of land on the newly developed West Bund of the Huangpu River as the art district. The 4-mile-long Longteng Avenue along the West Bund has already become home to dozens of museums and art galleries. When completed, the West Bund will be “Asia’s largest art corridor.”

The Chinese signs and development plans for “West Bund 2019” on Longteng Avenue claim that this four mile-long bund will be “Asia’s largest art corridor.” Photos by Zhang Hua, September 2019.

The West Bund is now home to large-scale museums such as the West Bund Art Center, the Long Museum West Bund, the Shanghai Center of Photography (SCoP). Also located in the area are relatively small art galleries, such as the Don Gallery and a branch of the ShanghART Gallery, as well as the nearby the Power Station of Art (PSA). These museums, art centers, and galleries have frequently featured contemporary art from artists living overseas, as well as in Shanghai and other parts of China.

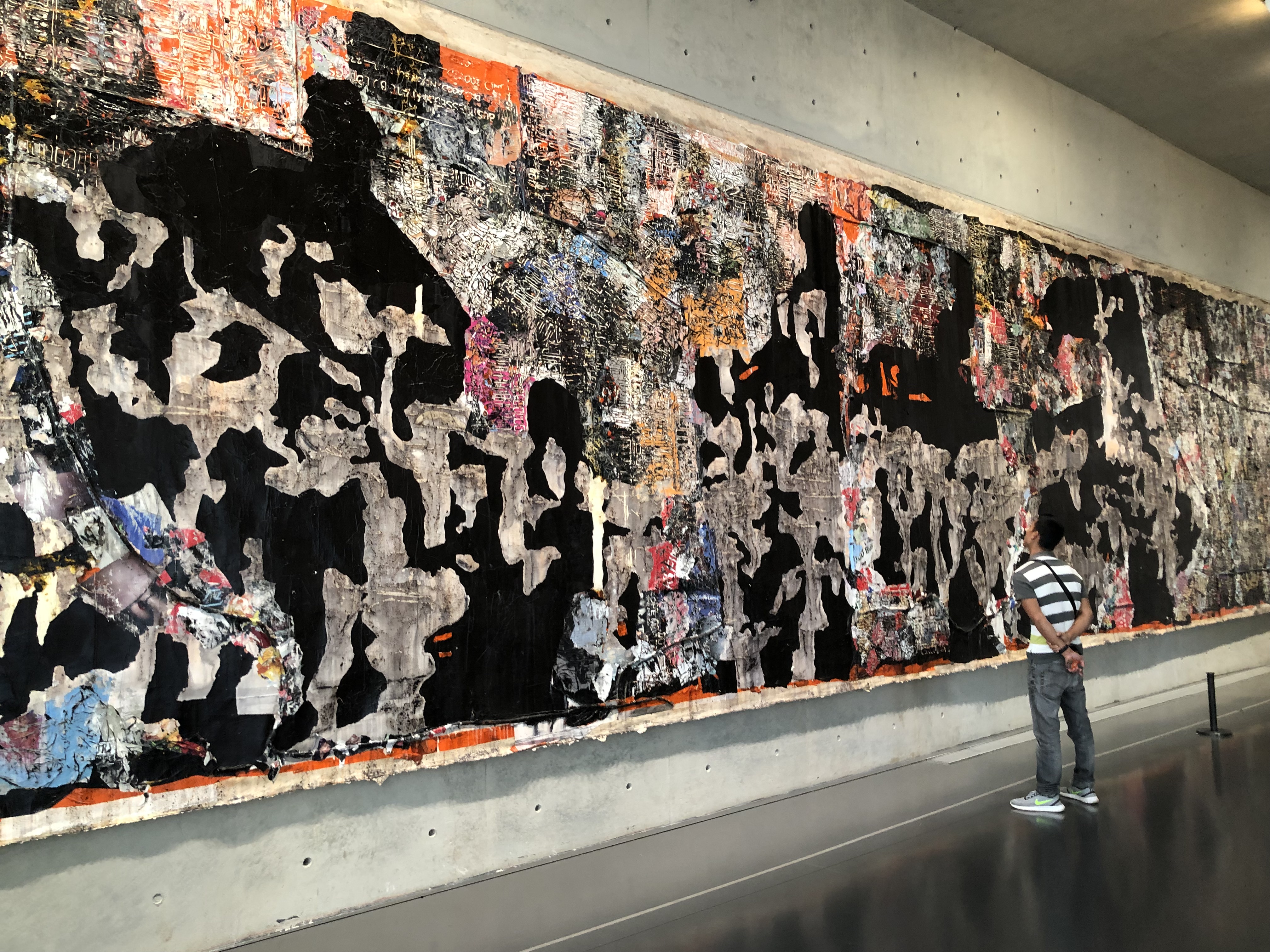

Left: In September 2019, the Shanghai Center of Photography (SCoP), a premier museum-quality venue dedicated to the art of photography, displayed a photo portray exhibition called “Close” by New York–based German photographer Martin Schoeller. Right: In September 2019, the Long Museum West Bund displayed “Los Angeles,” which consisted of many large-scale paintings of “social abstraction” by L.A. artist Mark Bradford.

Many of these newly built museums and art facilities in the West Bund were privately funded. For instance, the Long Museum West Bund, which was China’s largest private museum at the time of its opening, was founded by the Shanghai-born entrepreneur couple Liu Yiqian and Wang Wei in 2014.

Left: The Long Museum West Bund was founded in 2014 by Shanghainese entrepreneur couple Liu Yiqian and Wang Wei.The museum site was previously the terminal for coal shipping on the Huangpu River. Visitors to the museum can still see the view of a coal hopper unloading bridge from atop a retainer column built in the 1950s. Right: Designed by Liu Yichun, a Chinese architect at Atelier Deshaus, the Long Museum West Bund covers 33,000 square meters and dedicates up to 16,000 square meters to exhibitions.

The Le Freeport, a bonded warehouse built for the storage of artwork, has also found a home in the West Bund. Lorenz Helbling, the Swiss founder of ShanghART and one of the most respected avant-garde galleries in Shanghai, recently called the West Bund “Shanghai’s — if not China’s — most exciting up-and-coming art district.”

In addition to displaying and selling art pieces, some galleries also offer weekly or monthly public lectures about contemporary art. Most of the attendees are college students and young members of the middle class.

In 2017, there were 6.17 million total visitors to art galleries and museums in Shanghai, including 3.96 million visitors to state-owned galleries and 2.21 million visitors to private ones. Visiting a museum for middle class residents in Shanghai is not only a source of entertainment but also “a kind of education, a kind of lifestyle.”

The art gallery boom in Shanghai reflects the evolving cultural dynamics and aesthetic interests and preferences of the growing middle class in the city. Make no mistake, political and media control remain prevalent in Shanghai as elsewhere in the country. But at the same time, middle class residents in this cosmopolitan city have become increasingly dissatisfied with homogenized products and services, and are now demanding subcultural identity, individuality, and diversity.

Acknowledgments:

Editing: Kevin Dong, Ryan McElveen, and Anna Newby

Design: Rachel Slattery

Photos: Cheng Li