Chapter

02

PUBLIC HEALTH:

Ensuring equal access and self-sufficiency

Reimagining the future of health in Africa

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused enormous global disruption and the loss of many lives and livelihoods. The pandemic is still unfolding: There are currently more than 300 million infected and 5.5 million dead as of January of 2022 worldwide—with 9.4 million confirmed infected and more than 220,000 confirmed dead in Africa alone.1 The situation is still unfolding, with several SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern emerging since the onset of the pandemic.

COVID-19 has also exposed major flaws in the underlying logic of the pre-pandemic global health system. The assumption that infectious disease threats will emerge from the poorest countries and spread to wealthier ones has been dispelled. Unlike Ebola, which started in low-income countries and was largely contained, COVID-19 started in China and quickly engulfed developed countries in Europe and North America, sparing Africa to a large degree.

“The idea or rhetoric of global solidarity in the face of a pandemic rang hollow. Africa has experienced firsthand what vehement declarations of solidarity for poor and vulnerable countries meant.”

Weaker economies were mostly correlated with weaker public health systems and, therefore, greater public health risks. The Global Health Security Index ranked the United States first in pandemic preparedness, clearly not anticipating an irrational and anti-science political leadership. This development suggests that wealthier economies’ public health systems can be vulnerable to infectious disease threats.

The idea or rhetoric of global solidarity in the face of a pandemic rang hollow. Africa has experienced firsthand what vehement declarations of solidarity for poor and vulnerable countries meant. When the chips were down, almost every country and region prioritized their own interests.

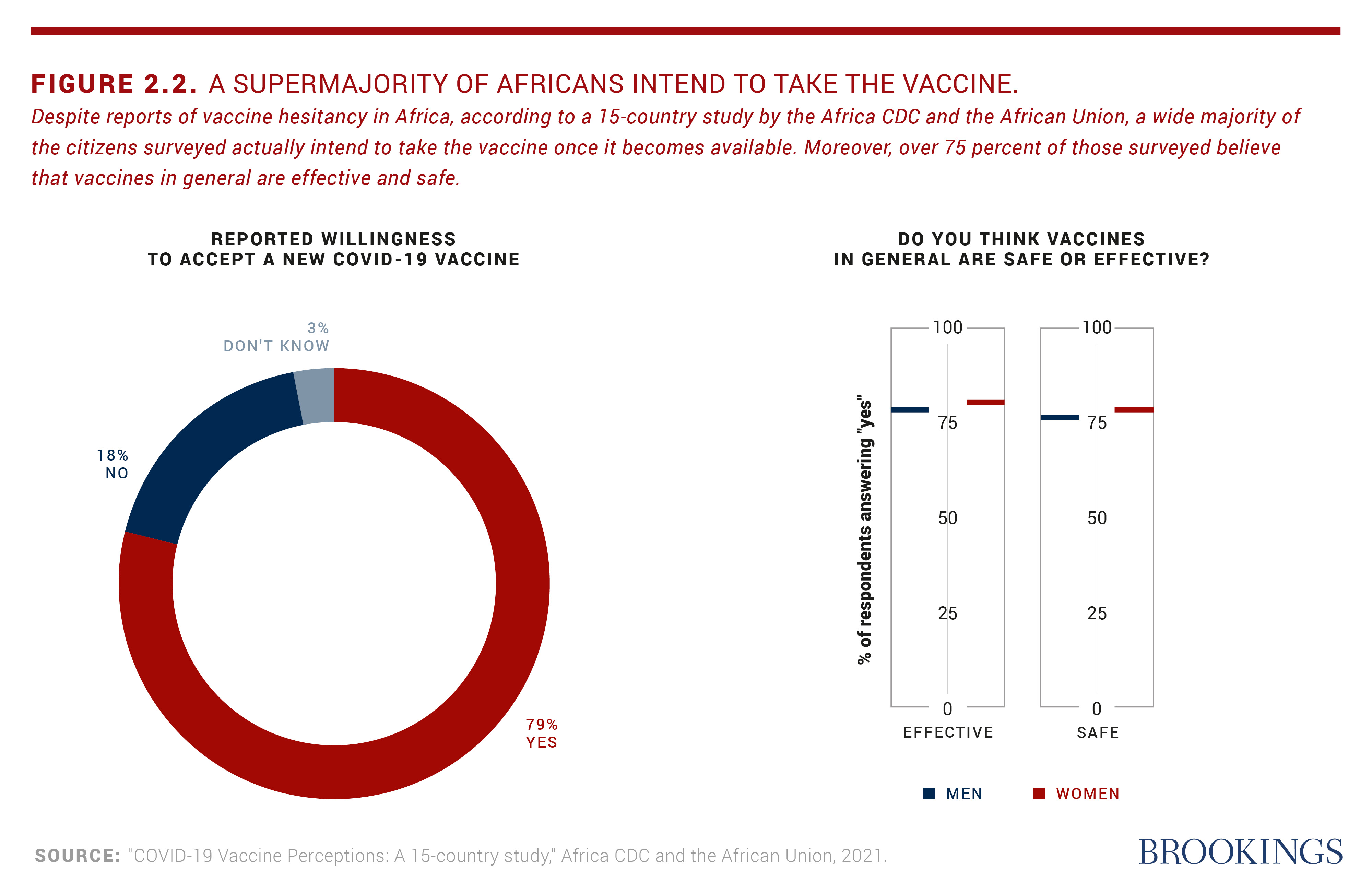

Despite strong efforts by multilateral institutions, weak commitment to multilateralism by some national political leaders exposed some long-standing fallacies. For example, the assumption that, in a global crisis like that which we saw in 2020, wealthier countries like the United States would step up to ensure the poorest and most vulnerable countries are protected. Instead, the world witnessed the hoarding of critical equipment like masks and ventilators in the wealthier countries—many looking only after their national interests. Similar actions have resulted in certain low-income countries in Africa reaching less than 5 percent of COVID-19 vaccination rate,2 while many developed nations achieved 70 to 90 percent coverage to date and are now administering booster vaccine doses.

Faced with such glaring inequity, African leaders emerged to exercise leadership, taking a continental approach through the African Union’s Partnership for Access to COVID-19 Tools, African Medical Supplies Platform, and African Vaccines Acquisition Task Team. This effort was led by private sector leaders as Special Envoys, the Africa Centers for Disease Control, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, and African Export-Import Bank—and supported by the World Bank.

“Mobilizing investments to ensure African children survive and thrive and women have access to quality reproductive and maternal health care as well as empowering girls and women through quality education and a conducive labor market will guarantee the future of Africa’s health and prosperity.”

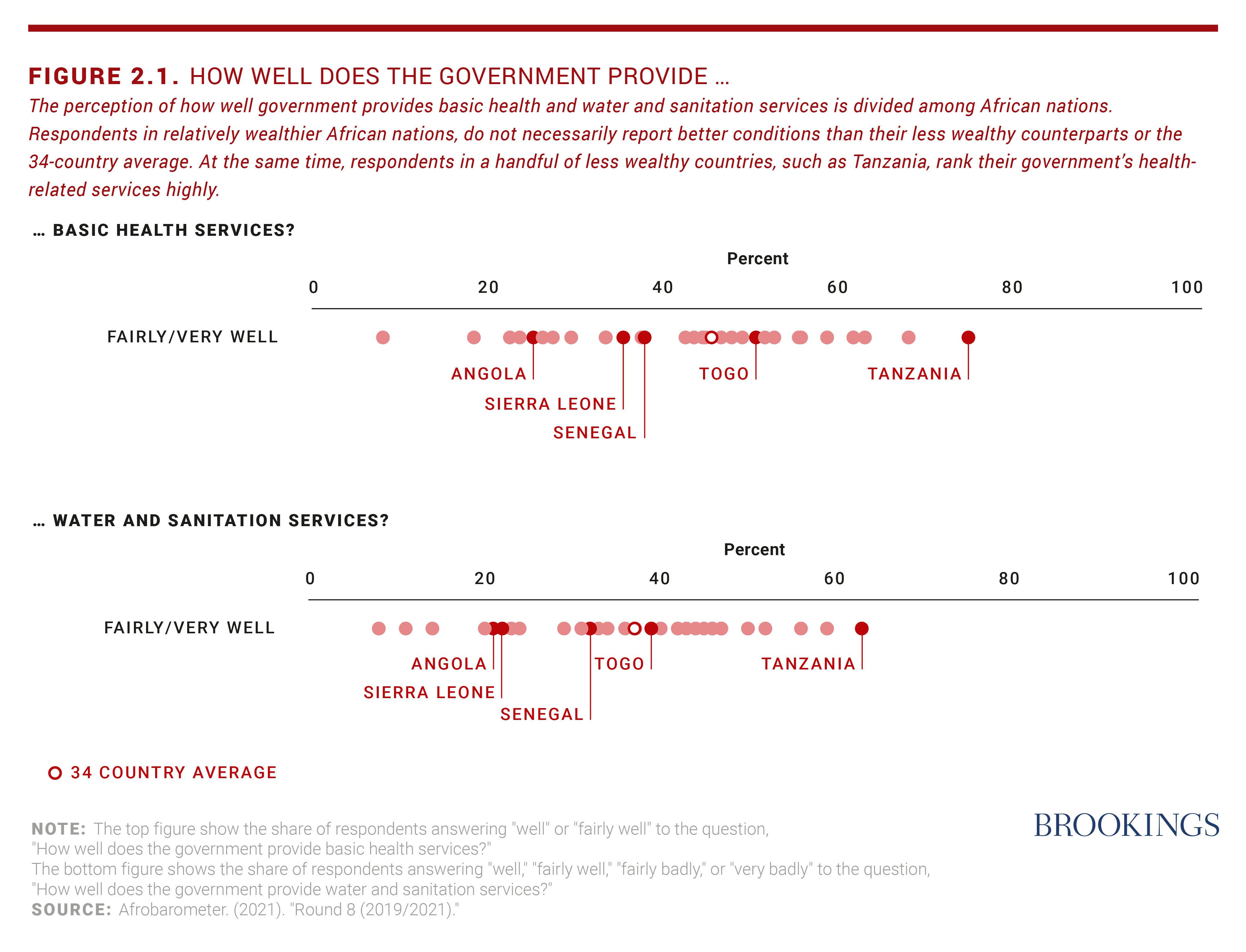

Yet, Africa’s development challenges persist: Political and security crises; slow demographic transition; high youth unemployment; increasing urbanization; rapid population aging; epidemiological transitions with rising noncommunicable diseases in the face of background endemic infectious diseases; child undernutrition and adult obesity; environmental uncertainties due to climate change (e.g., floods, droughts, rising temperatures); and slow progress in improving water, sanitation, and hygiene. While governments have managed to increase spending during the height of the pandemic, for many countries, general government expenditures on health will take until 2026 to return to pre-pandemic levels.

Despite these ongoing problems, the pandemic has created a reset moment for Africa’s health systems and an opening for leaders to reimagine—and then hopefully realize—a better future for health in Africa.

There are at least eight recommendations to shape the emergence of a brighter future of health in Africa.

- Protect and increase investments in the health of women, adolescents, and youth. With a large and increasingly young population, Africa represents the future of the world. By 2050, 60 percent of Africa’s 2.5 billion population will be under 25 years of age, potentially providing huge human capital and talent for its development and for the world. After decades of being left behind, African girls and women are rising, and the power and resilience of African women should not be underestimated. Mobilizing investments to ensure African children survive and thrive and women have access to quality reproductive and maternal health care as well as empowering girls and women through quality education and a conducive labor market will guarantee the future of Africa’s health and prosperity.

- Tackle inequalities by being intentional with inclusion, especially for marginalized and vulnerable populations. With fast-growing populations in many countries, increasing mobility, urbanization, and consequent social dislocations, neglecting the health needs of the poor and excluded groups will negatively impact everyone. On the other hand, orienting health systems to tackle the needs of the most vulnerable is likely to strengthen societal bonds of trust and cohesion to improve resilience. Already, young leaders on the continent are emerging with new ideas, such as the notion of “radical inclusion” in Sierra Leone.3 The nature of demand by citizens is becoming more sophisticated than in the past, requiring adaptive responses by governments, but it is important that all critical voices are included to build a better and stronger future.

- Balance reactive health care with prevention, promotion, and wellness. Africa’s “weak” health systems still can avoid the Lilliputian trajectories of the more advanced health systems. They can choose to reinvent the wheel. They can build community-based integrated health systems that promote health and well-being, rather than the potentially unsustainable path of focusing mainly on treating diseases. African countries can still balance the focus on the prevention of diseases (e.g., good nutrition, environmental sanitation, and the promotion of health and wellbeing) with treatment of acute illnesses, which may require expensive technologies and medical interventions for a small group of people. A primary health care approach offers a good foundation for treating basic diseases, strengthening public health, and engaging communities to build trust and accountability. However, this policy shift still requires improved domestic and external mobilization and investments, including innovative financing approaches.

- Optimize the health value chains in appropriately regulated markets to encourage health manufacturing to sufficiently deliver commodities, pharmaceuticals, and equipment. The health sector is labor-intensive and can create quality jobs. Encouraging African entrepreneurs to unlock the market potential of the health sector will help both deepen the sector’s resilience in the face of crises and create a form of insurance mechanism by ensuring a decentralized diversified manufacturing capacity for shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Tech transfer is good, but harnessing Africa’s own intellectual property is equally important.

- Seize the opportunity of digital technology, data science, and innovations for step-change in productivity in the health sector. It can strengthen data governance on the African continent to accelerate technological diffusion and innovation. With its young population and already-demonstrated propensity to drive and adopt innovations, Africa can build a strong multidisciplinary health workforce. It can put its people and communities at the center of its health system, rather than the medical industry.

- Build a pipeline for talent by connecting reforms to strengthen STEM education. With the need for health talent to drive Africa’s biotech and life sciences industry, addressing employment needs for its youth is critical. Such developed talent will drive research and development to discover new ways of treating old diseases and connect Africa’s biodiversity asset to address both old and new diseases. The future of the world may depend on it, as almost certainly there will be future infectious disease epidemics and pandemics, as well as the growing problem of noncommunicable diseases.

“Encouraging African entrepreneurs to unlock the market potential of the health sector will help both deepen the sector’s resilience in the face of crises and create a form of insurance mechanism by ensuring a decentralized diversified manufacturing capacity for shocks.”

- Rapidly implement the African Continental Free Trade Agreement as a catalyst to promote intra-African trade and economic integration, making progress towards the vision of Africa 2063. By orienting its trade in products and services, Africa will be able to harness tremendous energy, foster shared prosperity, and improve its population’s health and resilience. By harnessing the African Continental Free Trade Agreement, along with the new Africa Medicines Agency, the continent can improve availability, affordability, and security of supplies critical for improved health, such as personal protective equipment, biologics, pharmaceuticals, and medical devices.

- Encourage political participation, revitalize democratic governance, peacebuilding, and strengthened national and regional institutions, focused on the emancipation of the continent from a global system rooted in colonial and imperialist ideology. The next generation of leaders in politics, government, private sector, academia, civil society, and communities can emerge to change the narrative of Africa in the world.

Realizing a different, brighter, and more hopeful future for health in Africa is possible, even if it may require change from the present. The time is now for leaders to lift their gaze and start working towards that future.

Endnotes

- 1. The African numbers may be underestimated because of limited testing in the region compared to other parts of the world.

- 2. As of this writing.

- 3. The “radical inclusion” policy in Sierra Leone is allowing adolescent girls and women who get pregnant while in school to return to school and complete their education in safe environments, likely to reduce unsafe abortions, reduce mortality and empower the girls and women.

Viewpoints

Michel Sidibé reviews the global security ramifications of vaccine inequity and the regulatory system’s role in a well-functioning health ecosystem.

Olusoji Adeyi exhorts African countries to take financial responsibility for the continent’s fight against malaria.

Vera Songwe describes the financial challenges facing African health care systems and highlights homegrown institutions and innovative financing approaches to support Africa’s pandemic response.

Chidi Victor Nweneka and Tolu Disu outline developments in Africa’s vaccine manufacturing capacity and propose a three-pronged agenda to mitigate bottlenecks and ensure local ownership.

Christian Happi shares recent successes in Africa’s genomic capability and offers strategies to further the region’s scientific advancements in health.

Jean-Baptiste Nikiema discusses the role African governments can play in shaping health care markets.

Raymond Gilpin makes the case for investing in cleaner cooking fuels in Africa to address both health and climate challenges.