HOW WE RISE

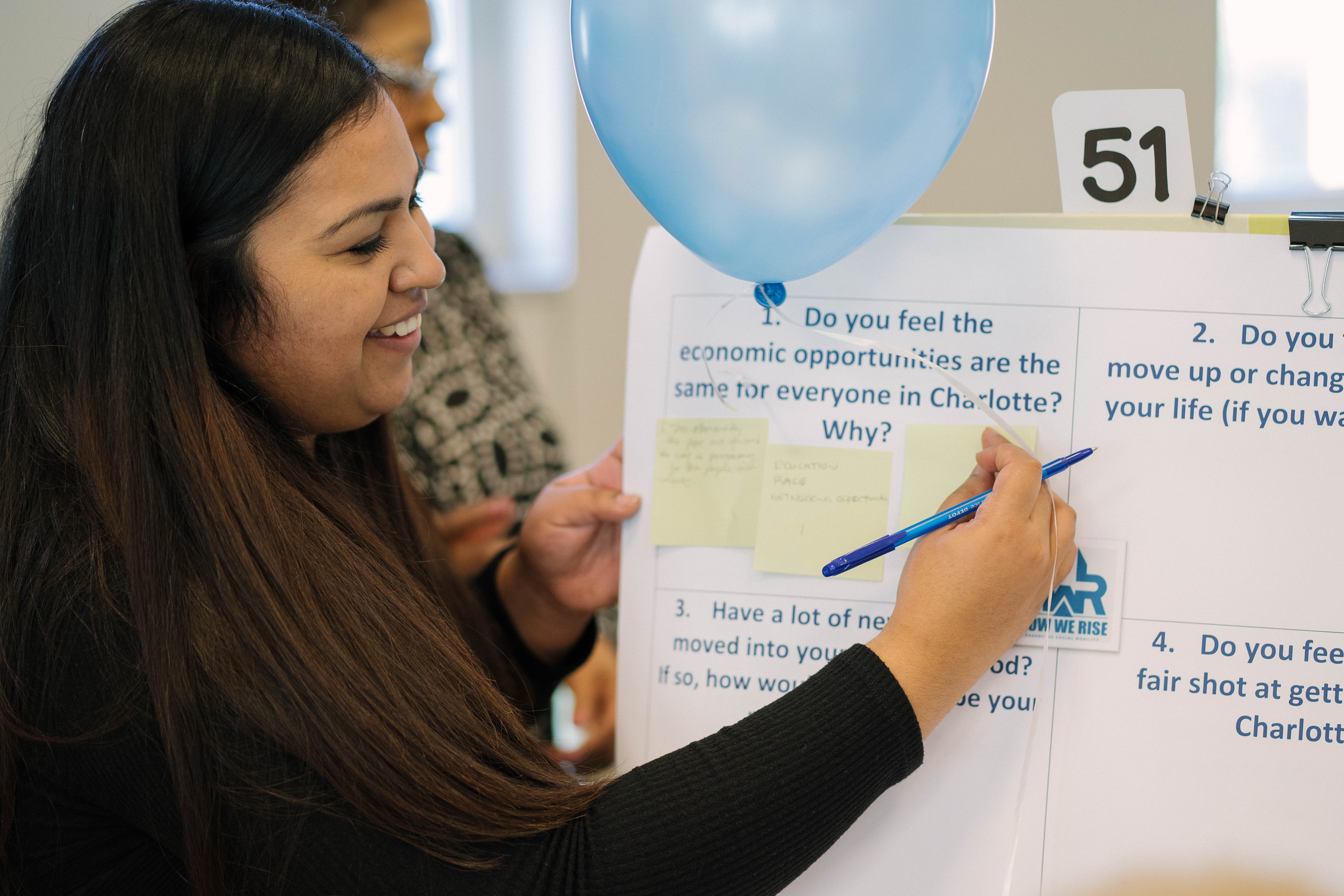

Charlotte, North Carolina, is a city rich with opportunities, but those opportunities are not equitably shared. In 2014, Charlotte placed 50th out of 50 in a ranking of cities for upward mobility. Now the city aspires to be a horizon community, one where all can rise. Social networks, providing access to support, information, power and resources, are a critical and often neglected element of opportunity structures. Social capital matters for mobility.

We analyzed over 30,000 interpersonal network configurations in the city, drawing on rich data from 177 representative residents of Charlotte. These networks were then evaluated for size (i.e., number of people), breadth (i.e., range of connection types, such as familial or professional) and strength (i.e., the value of connection as a source of assistance). We compared social networks by demographic group, especially race, income, and gender. In particular, we assessed networks in terms of their value for access to opportunities and resources in three domains: jobs, education and housing.

Below are our main empirical findings on social networks in Charlotte. A full methodology and further technical details are available here.

Download the Full Report

How We Rise: How social networks in Charlotte impact economic mobility

Analysis of social networks in Charlotte

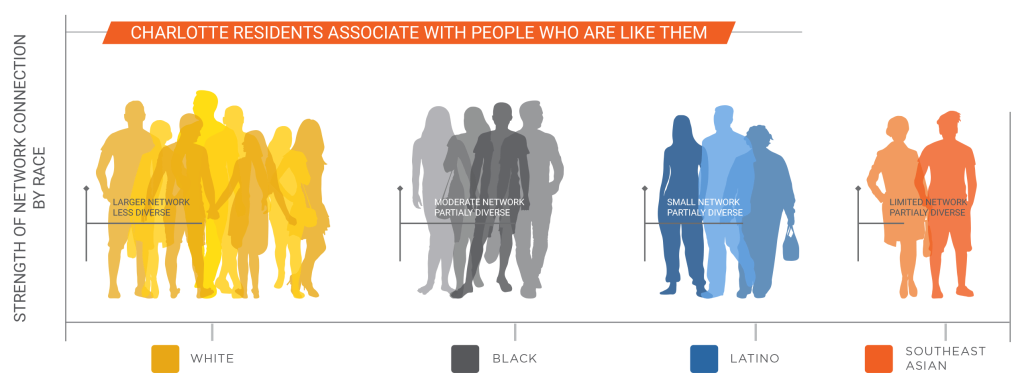

Social networks are strongly homogenous across demographic categories, especially by race. Black respondents have largely Black networks. Most striking, most whites have networks composed only of other whites.

Information and resources associated with social networks therefore largely flow within racial groups rather than between racial groups. This reflects in part the high levels of residential and educational segregation in the city.

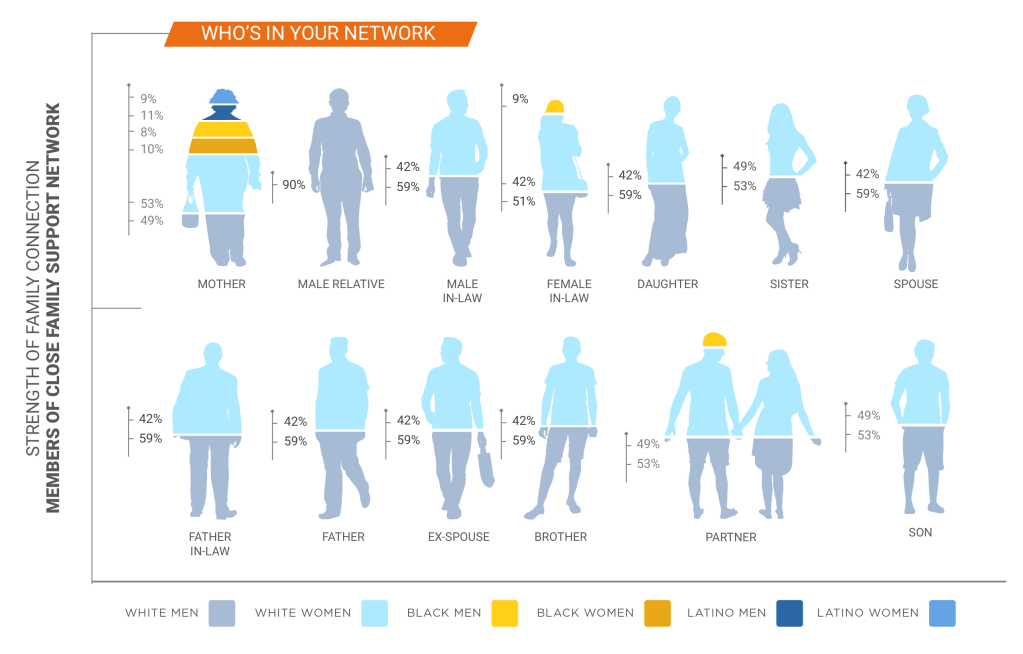

The character of social networks varies by race and gender. Whites see the greatest advantages. White men benefit from the richest pool of social capital, with a large, broad, and strong set of connections, including multiple professional contacts, family members, and personal associates. The networks of white women are not quite as valuable as for white men—though they do report good access to financial support.

Black women and especially Black men have less social capital than whites overall. Black women have larger networks than Black men, able to count on several people for support, information, advice, and mentoring—but these connections are not as strong for whites. For both Black women and men, access to financial support through social networks is much lower than for whites. Black men in Charlotte have especially weak networks. In fact, Black men typically rely on just one person for tangible support when exploring employment, educational, or housing opportunities.

The networks of Latinos are also small and relatively narrow and particularly reliant on family members. Of all the groups we analyzed, overall, Latinas (Hispanic women) are the least networked in Charlotte.

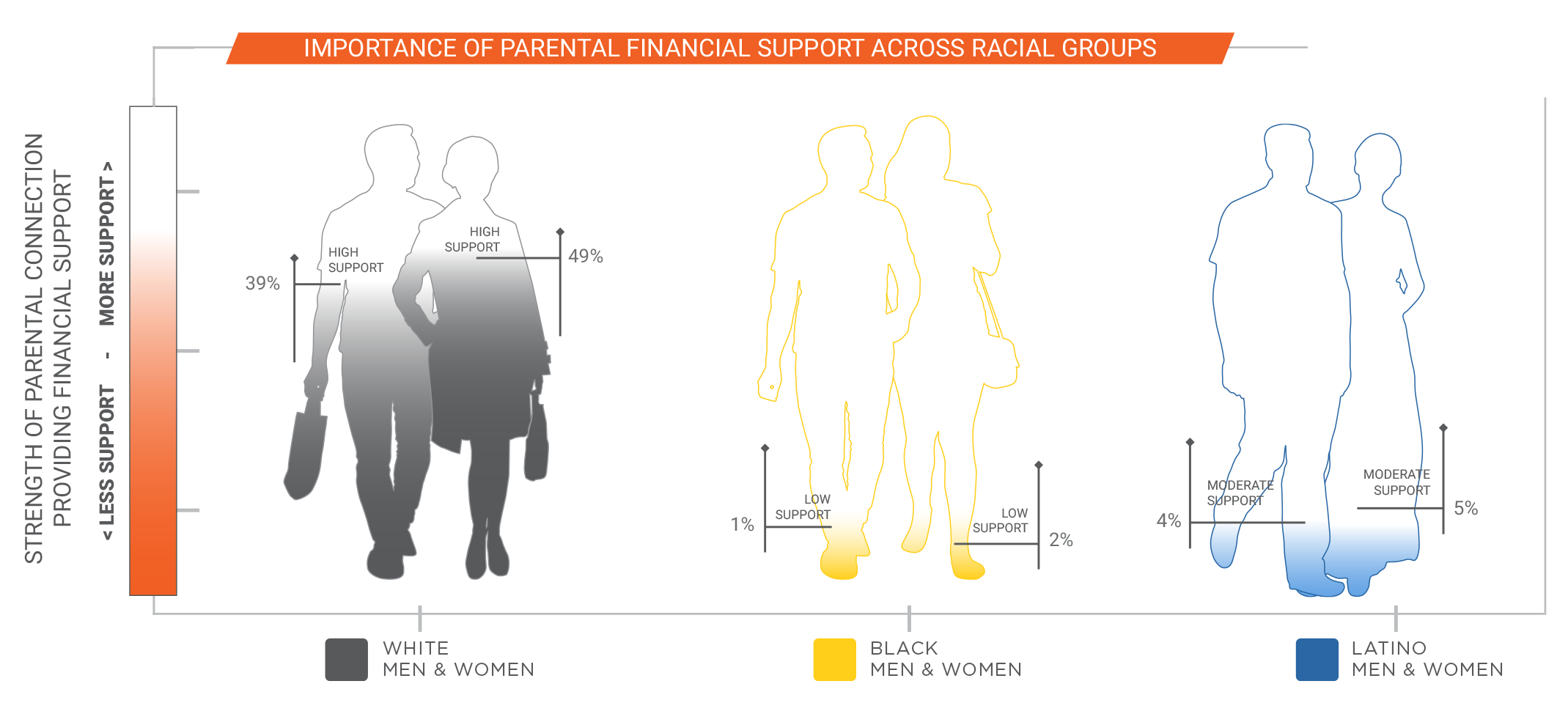

Whites report high levels of assistance from parents, especially financial support in relation to housing opportunities. Blacks receive only modest financial support from mothers, and none from fathers. Similarly, Latinos did not generally report assistance from parents.

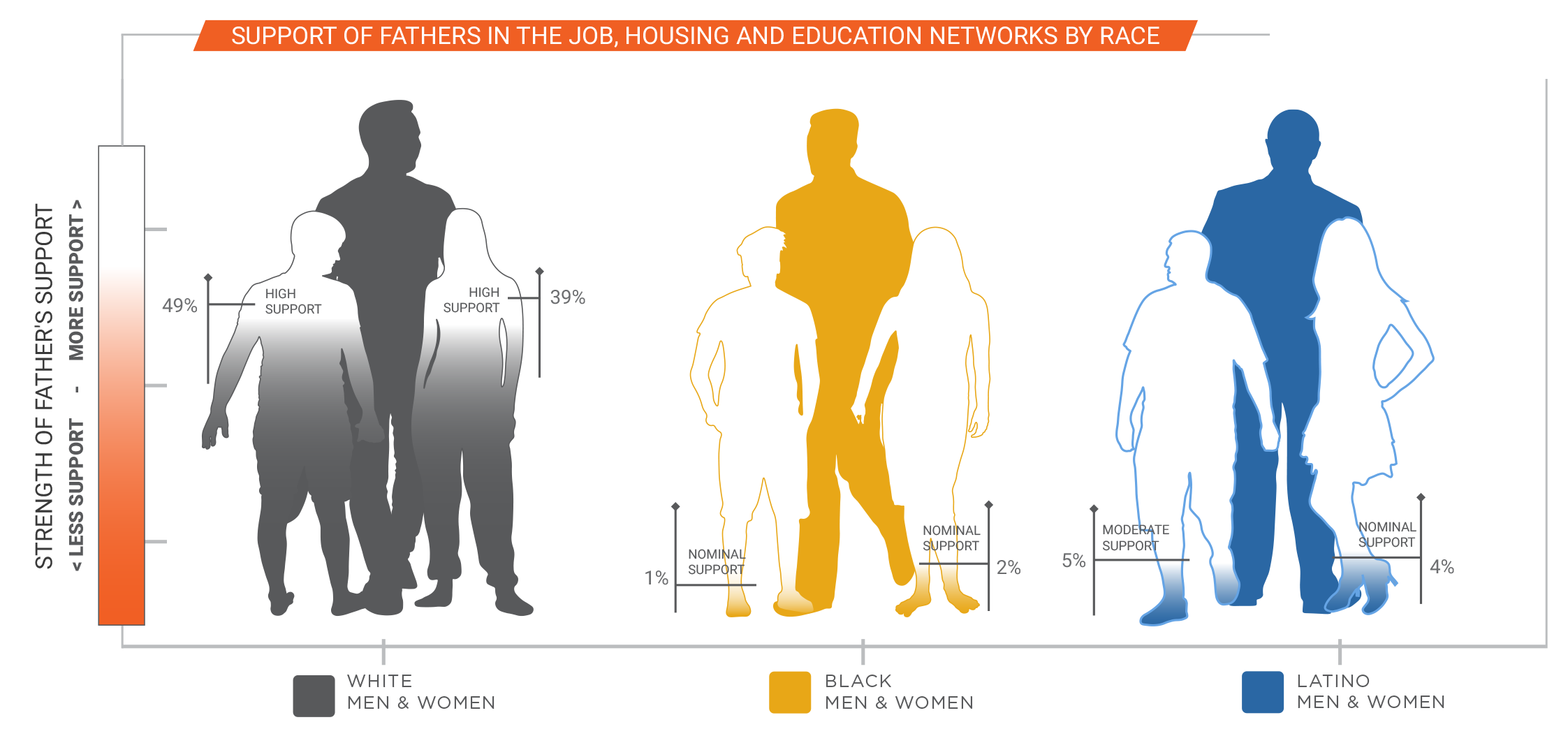

Overall, we find that fathers play an important supporting role for whites, but a much smaller role for Latinos, and are able to provide no real support to either Black men or Black women.

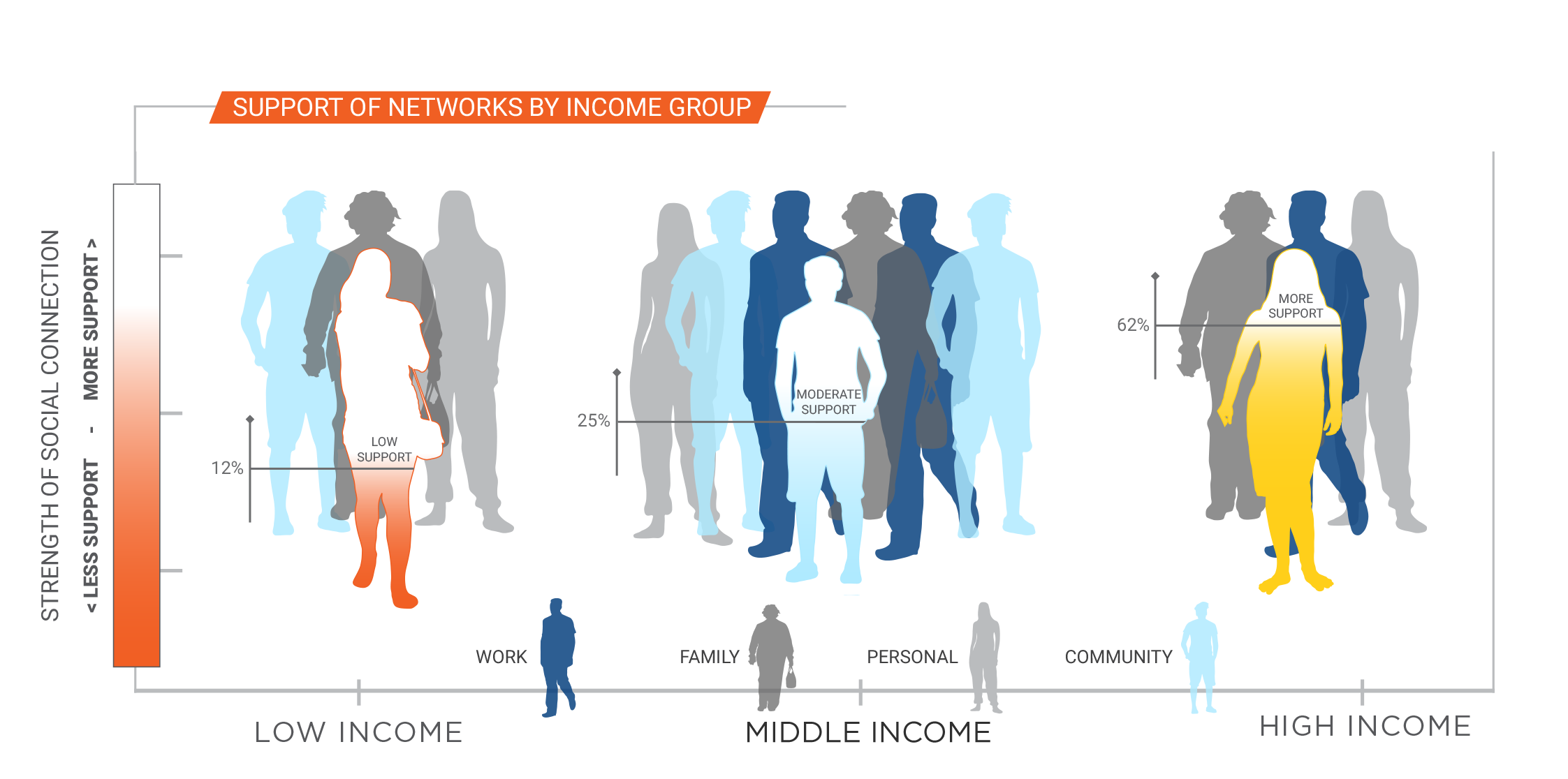

Assessing social networks by income, we find that middle-income residents have the broadest networks, compared to more affluent or poorer residents. But there is an important difference at the tails in terms of network strength. Higher-income respondents had fewer people in their networks, but those contacts were highly reliable for information, advice, networking, and for providing references. At the top of the economic ladder, social networks are small but strong.

We note that these differences by income overlap strongly with the race gaps described above, since the median income of whites is twice that of Black and Latino households in Charlotte.

Most social connections were formed in educational institutions (schools and colleges) or in the workplace. This highlights the connection between institutional settings and access and the accumulation of social capital. Exclusion from institutions means exclusion from opportunities to build valuable connections.

A history of inequality

The sharp divides in social capital contribute to Charlotte’s underperformance in terms of social mobility. The role of intergenerational networks is an especially stark illustration of broader inequalities: White wealth and support consistently cascade down the generations; not so for Blacks and Latinos.

But these social capital gaps do not emerge out of thin air. They are, to a large extent, the result of specific policy choices. We offer a brief, critical assessment of trends in housing policy, education policy, and criminal justice and policing.

Charlotte’s neighborhoods are strongly segregated by race (it is the 37th most segregated city in the U.S.), and notably, unlike most cities, has seen no decline in the level of segregation in recent years.

The public schools in Charlotte are also segregated by race, following a series of policy shifts. The segregation of Black and white elementary school students has in fact, been rising over recent decades. Black boys are much more likely to be excluded from school than whites. In 2012, Black boys accounted for 20,090 short-term suspensions, compared to 2,643 for white boys.

Black men also face much higher rates of incarceration. In Charlotte, Black men are almost 10 times more likely to be incarcerated than white men. Black male unemployment rates are also twice that for white men.

These trends result from specific policy choices made, or policy choices avoided. To a large extent, the social networks of Charlotte residents reflect and reinforce the inequities in housing, education, employment, and criminal justice. We focus in particular on the multiple injustices faced by Black males, and conclude that in Charlotte there is not only underinvestment, but specific, aggressive disinvestment in Black boys.

Policy opportunities

What is be done? We do not offer a blueprint for building social capital but suggest some potential paths forward for the city. Most important, three commitments must be made by Charlotte’s civic, business, and political leaders:

- Candidly engage with the racial dynamics of the city.

- Work collaboratively across racial lines to identify who is accountable for equity goals.

- Identify and execute on policy areas where the greatest racial equity gains can be achieved in the next 3-5 years.

As a result of authentically acting on these commitments, a series of policy goals and approaches could emerge. The city could, for example:

- Set a goal to drive down school suspension and incarceration rates among Blacks compared to those of whites.

- Develop a racial equity plan for Charlotte that articulates measurable, highly impactful equity goals.

- Transition away from a juvenile justice system and school suspensions.

- Support young Black and Latina mothers, measuring success by rates of maternal mortality.

- Invest heavily in a college savings account for all kindergartners in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (CMS), and make additional payments for lower-income students over time.

Most importantly, these equity goals should be driven by those who are least advantaged. Charlotte’s divisions, not least in social networks, reflect choices made in the past—choices that today’s leaders and residents in Charlotte can and should make differently in order to create a true horizon community.

This report is part of The Brookings Institution’s How We Rise project, a larger series of research and analysis that helps to explain the dynamics of social connections and the policy solutions that intentionally focus on the social network determinants of economic mobility and equity.

The How We Rise project is part of the Race, Prosperity, and Inclusion Initiative, Brookings’s cross-program effort focused on issues of equity, racial justice, and economic mobility for low-income communities and communities of color.