06

Good governance:

Building trust between people and their leaders

Institutional resources for overcoming Africa’s COVID-19 crisis and enhancing prospects for post-pandemic reconstruction

Popular explanations for Africa’s “lucky escape” from COVID-19’s most devastating effects have largely focused on the continent’s natural endowments, especially its youthful population and warm weather. When Africa’s own agency is recognized, observers tend to give credit to its governments’ early and aggressive lockdown measures and consistent messaging about wearing face masks. While such early government actions likely saved thousands of lives, Africa’s citizens, who largely complied with extremely inconvenient top-down measures even where governments’ administrative and enforcement capacities were weak, deserve praise as well.

“While early government actions to prevent the spread of COVID-19 likely saved thousands of lives, Africa’s citizens, who largely complied with extremely inconvenient top-down measures even where governments’ administrative and enforcement capacities were weak, deserve praise as well.”

Importance of political capital in pandemic crisis management and recovery

Ordinary Africans’ contribution to the success of lockdown programs highlights the importance of state legitimacy and trust in government for securing compliance with necessary but arduous government orders, especially those vital to public health and safety.1

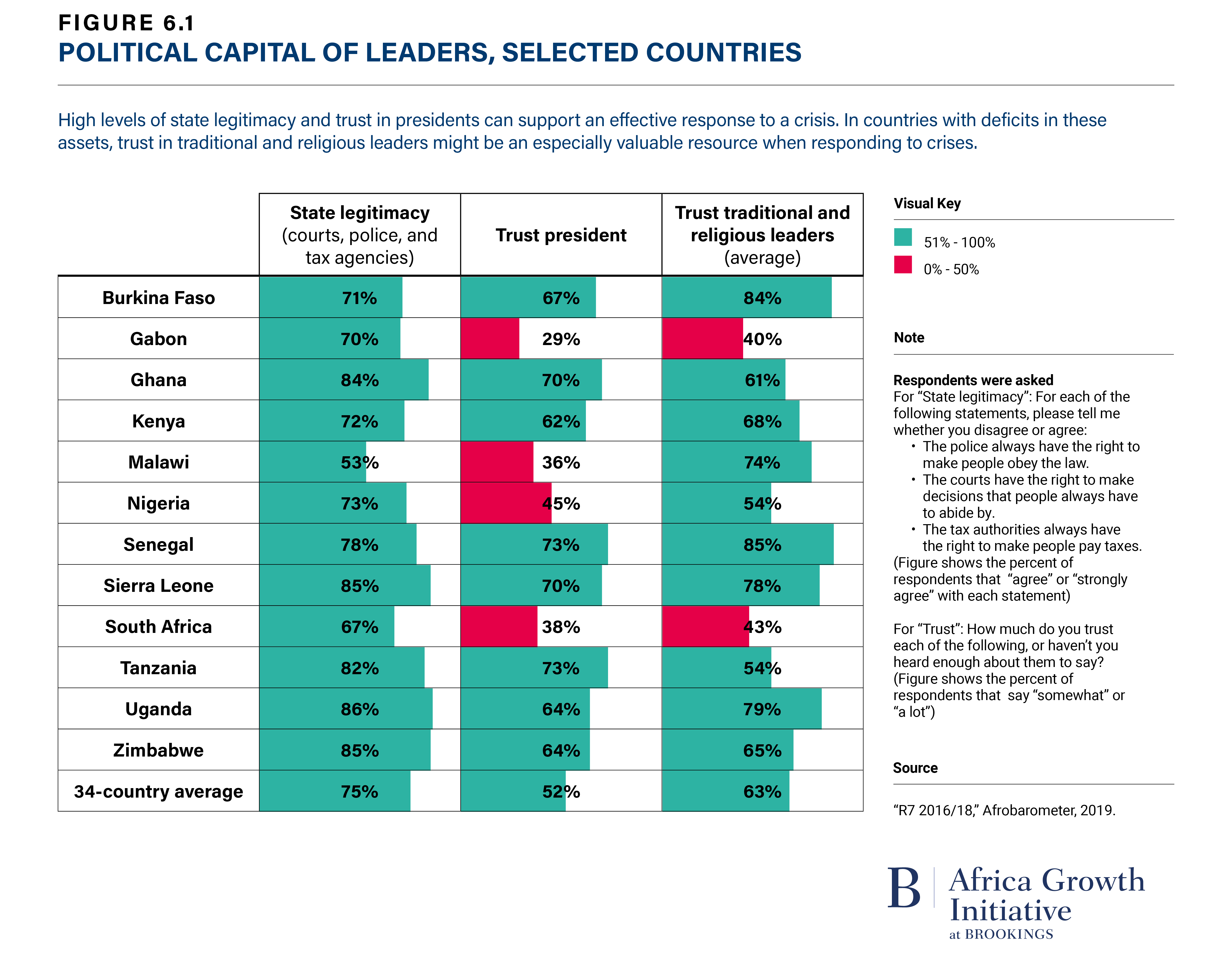

An examination of recent COVID-related events and Afrobarometer surveys in 34 African countries can provide more insight into this phenomenon. For example, Ghana has relatively strong institutions, with free media, strong opposition parties, and independent judiciaries. Before the pandemic, in Afrobarometer’s 2016/2018 surveys, Ghana’s core state institutions enjoyed very high levels of perceived legitimacy (84 percent), and President Nana Akufo-Addo was trusted by 70 percent of citizens. In contrast, Malawi ranked lowest in perceived institutional legitimacy (53 percent), and its then-president, Peter Mutharika—before losing his bid for re-election in June 2020—enjoyed the trust of just 36 percent of Malawians (Figure 6.1).

As the pandemic set in, public responses to COVID lockdowns varied significantly: Ghanaians accepted the lockdown measures their president announced in March 2020 even before the subsequent unveiling of economic and social relief packages. Malawi’s government, on the other hand, has faced considerable public resistance to anti-pandemic measures, including a successful court case challenging a lockdown on the basis of undue economic harm. Other factors, such as Malawi’s relatively greater poverty, may also play a role in the two peoples’ divergent responses to COVID-19 measures, but it seems likely that perceptions of their leaders and institutions helped shape citizens’ willingness to follow their dictates.

Another pairing makes a similar point: In Senegal, where 73 percent of citizens expressed trust in the president, the COVID-19 response has drawn international praise, while Nigeria (where trust for the president hovers around 45 percent) has contended with widespread flouting of public health guidelines and the looting of government warehouses storing COVID-19 relief supplies.

Enhancing prospects for overcoming Africa’s COVID-19 crisis and post-pandemic reconstruction

“If political capital can aid in the management of a pandemic, then African leaders must aim to create an environment for its conversation or enhancement as they confront COVID-19 and the next crisis.”

If political capital can aid in the management of a pandemic, then African leaders must aim to create an environment for its conservation or enhancement as they confront COVID-19 and the next crisis.

But threats to public trust are often on the horizon, especially in times of crisis: Reports of irregularities and corruption in the management of COVID-19 funds and relief not only impede the effectiveness of those measures but also undermine trust and legitimacy in government leaders and core institutions.2

Excessive reliance on coercion in the enforcement of COVID-19 measures can be detrimental as well.3 Similarly, attempts by some governments to leverage the pandemic to introduce repressive legislation and curb media freedoms and other civil liberties will only erode the democratic governance gains of the past 20 years and likely face significant popular pushback.4

“African governments can shore up their deficits and strengthen their responses to COVID-19 and other crises by tapping into the political capital of informal leaders, such as religious and traditional leaders.”

African governments can shore up their deficits and strengthen their responses to COVID-19 and other crises by tapping into the political capital of informal leaders, such as religious and traditional leaders. On average, almost two-thirds (63 percent) of Africans expressed trust in these non-elected leaders (69 percent for religious leaders and 57 percent for traditional leaders), although these trust levels, too, vary widely by country, from just 40 percent in Gabon to 85 percent in Senegal (Figure 6.1). Indeed, some African presidents have recognized this organic institutional resource and explicitly mobilized it in managing the pandemic through consultations with informal leaders (South Africa) and public acknowledgements of their important contributions in sensitizing and encouraging compliance in their communities (Nigeria and Uganda).

In conclusion, African governments will be in much better position to effectively overcome the COVID-19 crisis and enhance prospects for post-pandemic reconstruction if they show true commitment to conserving and deepening domestic political capital, strengthening the social contract with their citizens, and governing accountably.

Endnotes

- 1. See also Robert A. Blair et al., “Public Health and Public Trust: Survey Evidence from the Ebola Virus Disease Epidemic in Liberia,” Social Science & Medicine 172 (January 2017): 89-97, which highlights the extent to which trust in government was a critical resource for securing the public cooperation necessary to overcome the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

- 2. For example, Pearson’s r for the correlation between trust in the president and perceived corruption in the office of the president for Afrobarometer Round 7 is -.387, significant at the 0.01 level. See Michael Bratton and E. Gyimah-Boadi, “Do Trustworthy Institutions Matter for Development? Corruption, Trust, and Government Performance in Africa,” Afrobarometer Dispatch 112 (August 2016)

- 3. In April, Kenya and Nigeria reportedly had more citizens killed by security agents “enforcing” pandemic-related restrictions than by the coronavirus. See Alison Sargent, “Curfew Crackdowns in Several African Countries Kill More People than COVID-19,” France24, April 17, 2020. “Coronavirus: What Does COVID-19 Mean for African Democracy?” BBC, May 15, 2020.

- 4. Uganda, where the government has used COVID-19 regulations as a pretext for cracking down on the opposition and media (see “Authorities Weaponize COVID-19 for Repression,” Human Rights Watch, November 20, 2020), is just one of 80 countries where Freedom House says the state of democracy and human rights has deteriorated during the pandemic (Sarah Repucci and Amy Slipowitz, Democracy Under Lockdown (Washington, D.C.: Freedom House, 2020)).