From relief to recovery

What to know

In normal times, small businesses are constantly being created and destroyed. This churn makes entrepreneurship a risky journey for individual business owners, but can be a good thing for regional and national economies to the extent that it represents the “creative destruction” that creates economic progress.[i]

Unfortunately, COVID-19’s small business shock is not creative destruction, but destructive destruction. At the height of the crisis, April 2020, 90% of small business owners said that COVID-19 had negatively affected their operations.[ii] Some small businesses were better prepared, but overall, businesses struggled because of necessary regulations to guard public safety that limited consumer demand—not due to being less productive than their competitors. Simply letting businesses fail through no fault of their own would not only cost jobs, but would destroy all the intangible learning and expertise that small business owners have developed in tandem with their employees. This “firm-specific capital” can be lost very quickly, and is very difficult to transfer to another business or rebuild through an additional business.[iii] As a result, widespread small business failures could drastically lengthen the time it takes for the labor market to recover.

Put simply, for a variety of reasons, relief is still necessary to avert further business destruction. But there are not enough public resources to give capital to every small business, which means that relief should be targeted to businesses COVID-19 hit hardest. Evidence suggests that three factors matter in targeting:

Size: Young microbusinesses—those under 5 years old and with fewer than 10 employees—are more likely to contract and close during an economic downturn. During the Great Recession, for example, young microbusinesses experienced a 22% decline in employment, compared to a 7% decline for young businesses with 10 to 250 employees.[iv] We’d expect the same trends to hold during COVID-19.

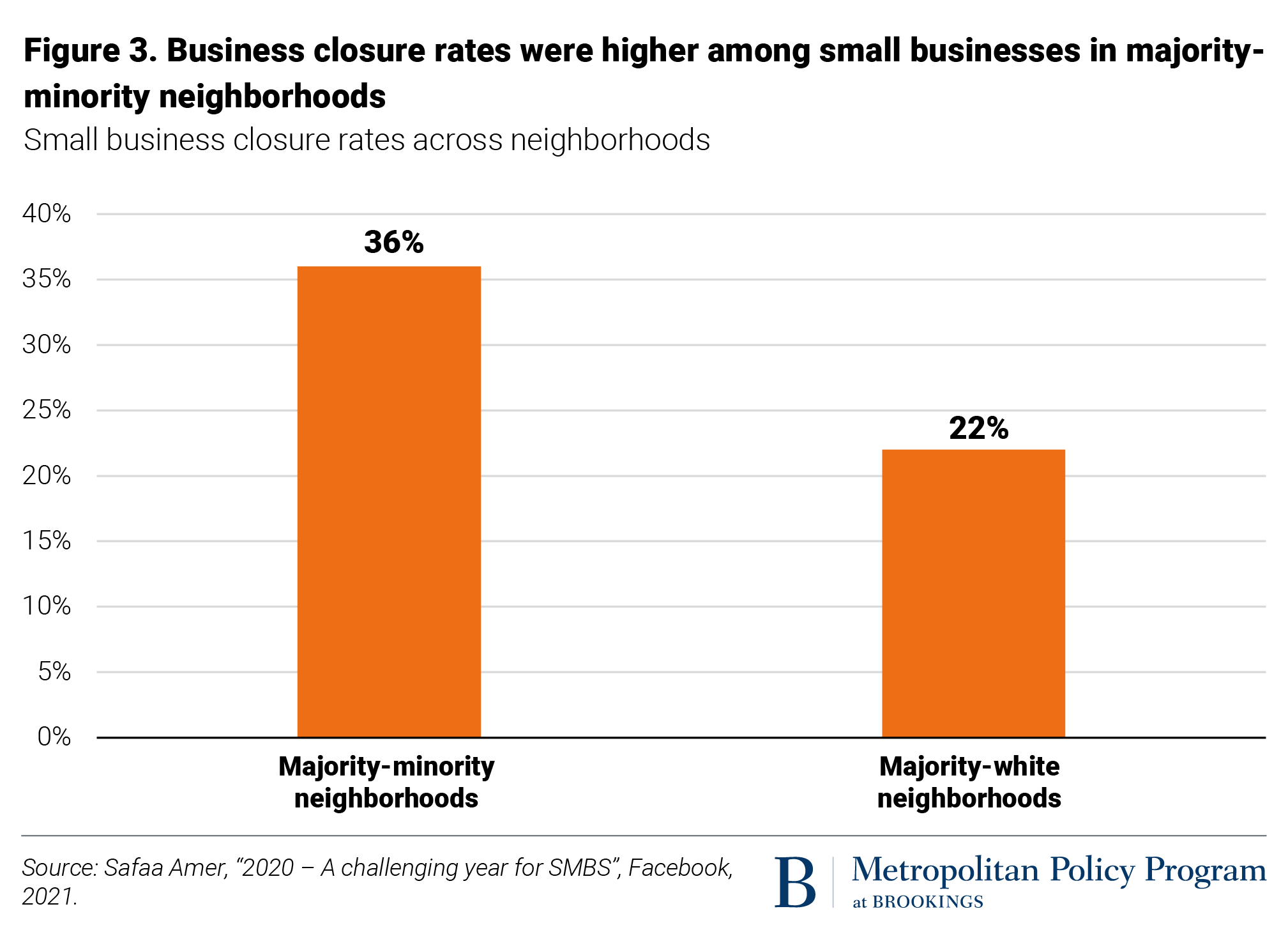

Location: During COVID-19, business closure rates varied across neighborhoods. Business closure rates were higher among small businesses in majority-minority neighborhoods (36%) compared to businesses in majority-white neighborhoods (22%).[v]

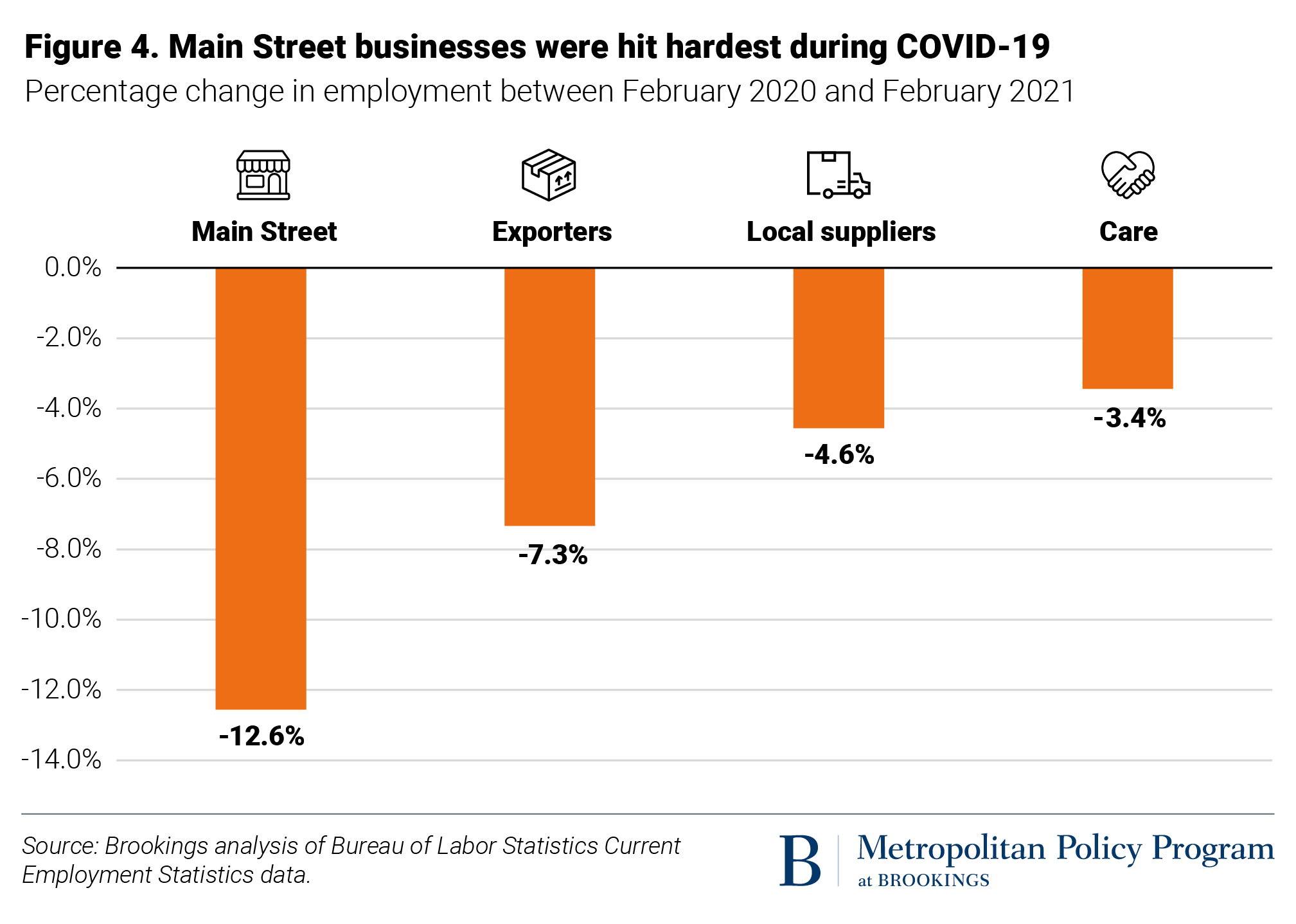

Industry: One reason why majority-minority neighborhoods had higher closure rates was that businesses in COVID-19-disrupted industries were disproportionately concentrated in those neighborhoods. Different than the 2001 or 2007-08 recessions, the COVID-19 economic crisis hit food services, retail, and accommodation industries hardest—all Main Street industries that employed millions of lower-wage workers (see Figure 4). While employment rates have nearly rebounded for high-wage workers, employment rates for low-wage workers are 28% below their pre-pandemic peak.[vi]

How to respond

There are three steps that local leaders can take to deliver small business relief:

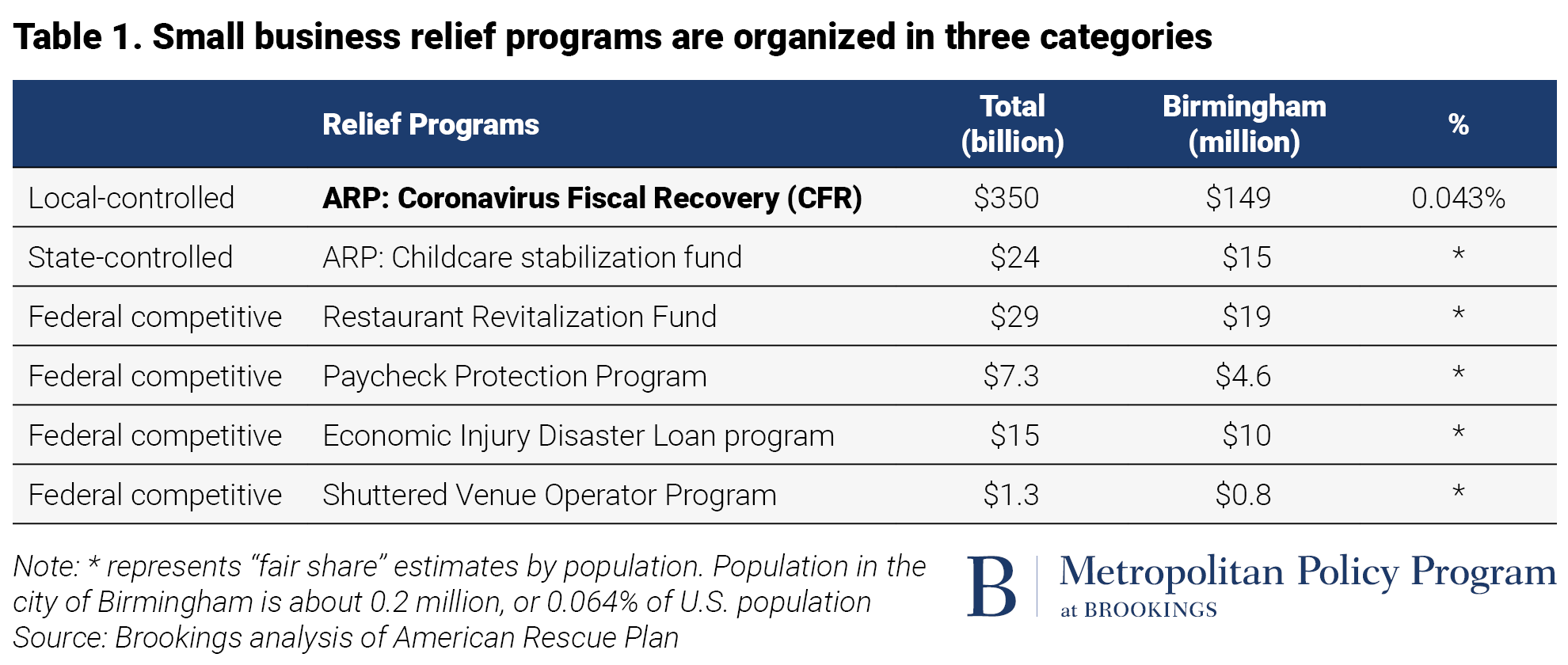

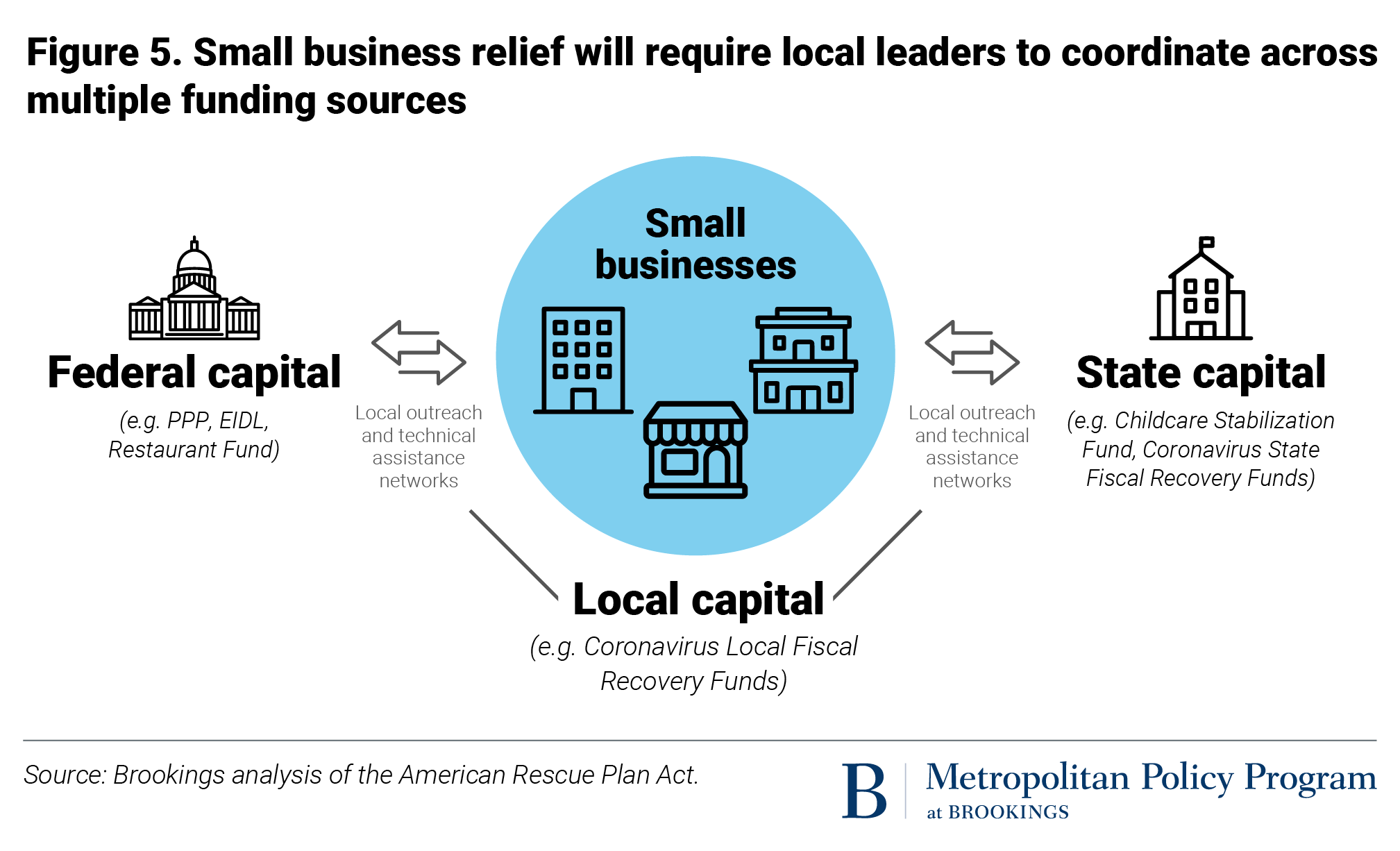

1. Map the small business relief programs within the American Rescue Plan. Local leaders must understand the three streams of resources they can deploy to support small businesses during the relief stage. First, the American Rescue Plan provided local, state, and tribal governments $350 billion in Coronavirus Fiscal Recovery (CFR) funds to give them flexibility in addressing the negative economic impact of the pandemic, including direct support to small businesses. Second, there are federal allocations for which small businesses must compete, including the Restaurant Revitalization Fund ($29 billion), Paycheck Protection Program ($7.25 billion), Economic Injury Disaster Loan program ($15 billion), and Shuttered Venue Operators Grant ($1.25 billion). Together, the federal government has made available about $50 billion in new small business relief. Third, ARP also included a new $24 billion child care stabilization fund that works through states to extend relief to child care providers.

Understanding the landscape of programs in ARP and how those allocations could be localized is a critical first step. To illustrate, we selected Birmingham, Ala., population 210,000. If Birmingham were to receive its share of competitive federal programs and the state-controlled Child Care Stabilization Grants, it could receive about $50 million in small business relief. That sum is the functional equivalent of one-third of its $149 million flexible CFR allocation, so it is extremely important that local governments work to acquire their fair share of those federal competitive funds and state-controlled funds.

2. Use flexible CFR funds in small business outreach and technical assistance networks. Many cities built technical assistance and outreach networks for their small businesses to obtain loans from the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) or the Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) program. They should now allocate their locally controlled CFR funds to support those networks through grants to chambers of commerce, community-based nonprofits, and entrepreneurship support organizations—any entity that has connectivity and trust with small business owners, particularly small businesses in historically underserved communities. These networks can deploy trusted brokers to connect small businesses to federal relief programs, keep them afloat until consumer demand returns this summer and fall, and ensure that their loans are forgiven to avoid significant debt loads. Another ARP provision—the Small Business Administration’s Community Navigator Pilot Program—is designed to support these local networks with competitive grants.[vii] To maximize a local area’s fair share of the state-controlled Child Care Stabilization Grants, cities should expand their small business outreach networks to bring in community-based intermediaries with connectivity to child care providers, including associations for the education of young children (AEYCs); Child Care Resource and Referral agencies (CCR&Rs); and Shared Service Alliances (SSAs).[viii]

- Example: Detroit Means Business. Last spring, Detroit officials worked alongside private, philanthropic, and nonprofit leaders to develop a system of small business support. The result—the Detroit Means Business program—is designed to prepare small businesses with fewer than 50 employees to safely and successfully operate during the COVID-19 crisis. The coalition helps small business owners work with experts to find grants, loans, and other financial resources during the COVID-19 crisis. Additionally, small business owners who have specific questions about accounting, human resources, marketing, legal, or business reopening operations can schedule a one-on-one virtual consultation with a small business expert.[ix]

3. If necessary, utilize flexible local funding to provide direct aid to small businesses. As federal small business relief programs are exhausted this spring and summer, local government officials will decide if they want to provide capital directly to small businesses using their CFR funds. We recommend exhausting other options first, as directly allocating flexible local capital to small businesses means that those funds cannot be used in other critical areas of economic support. Local governments should coordinate with their states to ensure they are not duplicating efforts. A sensible division of labor would be that states use their CFR funds to provide capital while local governments invest in outreach and technical assistance infrastructure to ensure underserved entrepreneurs can access those funds.

- Example: Energize Colorado Gap Fund. This fund is a state-led public-private partnership to distribute capital to several community development financial institutions (CDFIs), regional loan funds (RLFs), and other nonprofit lenders. Those lenders have distributed grants and loans to over 2,000 small businesses, who apply for assistance through one centralized application. These nonprofit lenders have strong relationships with underserved communities and are more accessible for business owners who do not have relationships with traditional banking institutions, giving Energize Colorado wider reach in providing aid to the small businesses it aims to serve.[x]

Footnotes

[i] Decker, Ryan, et al. “The role of entrepreneurship in US job creation and economic dynamism.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 28.3 (2014): 3-24.

[ii] U.S. Census Bureau Small Business Pulse Survey.

[iii] Hamilton, Steven. “From Survival to Revival: How to Help Small Businesses through the COVID-19 Crisis.” The Hamilton Project (2020).

[iv] Liu, Sifan, and Joseph Parilla. “What the great recession can tell us about the COVID-19 small business crisis.” Brookings Institution (2020).

[v] Safaa Amer, “2020 – A CHALLENGING YEAR FOR SMBS”, Facebook, 2021; Brookings analysis of Opportunity Insights data.

[vi] Economic Tracker, Opportunity Insights, https://tracktherecovery.org/

[vii] Community Navigators, U.S. Small Business Administration. https://www.sba.gov/local-assistance/community-navigators

[viii] Falgout, MK. “Optimizing Distribution of American Rescue Plan Funds To Stabilize Child Care.” Center for Amerrican Progress (2021)

[ix] Lewis, Pamela D., “Supporting microbusinesses in underserved communities during the COVID-19 recovery”, Brookings Institution (2020)

[x] Dinkins, Reniya and Michael Zhu, “Overcoming bias in small business relief in Colorado”, Brookings Institution (2021)

The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. As such, the conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its authors, and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars.

This report is made possible by the Kresge Foundation and the Shared Prosperity Partnership, for which the authors are deeply appreciative. We also want to thank colleagues who provided valuable feedback on the report: Alan Berube, Annelies Goger, Pam Lewis, Tracy Hadden Loh, Rob Maxim, and Mark Muro. The authors also thank Michael Gaynor for editing, Luisa Zottis for layout and design, Alec Friedhoff for his design of the data interactive, David Lanham for his communications leadership, and Jade Arn and Rowan Bishop for help on outreach.