Editor’s Note: This analysis is part of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy, which is a partnership between Economic Studies at Brookings and the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national health care debate with rigorous, evidence-based analysis leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings. USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative research on the prices of health care services is supported by Arnold Ventures.

In the coming months, Congress may consider policy changes aimed at expanding coverage and reducing overall health care spending, perhaps as part of a broader reconciliation bill. That debate may include discussion of proposals to create a public option, a publicly operated health insurance plan that people who buy coverage on the individual market can purchase in lieu of a private plan.[1]

A common rationale for creating a public option is that a public option could pay health care providers less than existing private plans, just as the Medicare program pays providers less than commercial insurance plans. Paying lower prices would, in turn, allow a public option to set lower premiums or impose less enrollee cost-sharing, which would directly reduce consumers’ costs and reduce the federal government’s cost of subsidizing premiums and cost-sharing (in some combination).

This analysis considers how a public option would need to be designed to replicate Medicare’s ability to pay providers substantially less than private plans while still eliciting provider participation. In brief, I argue that a public option would likely need two key features. First, it would need to set prices administratively (as the Medicare program does) rather than through negotiations with providers (as private insurers do). Second, it would need to be impossible for a provider to serve patients covered by the public option’s private competitors without also serving patients covered by the public option.

The analysis then considers whether there is still a rationale for creating a public option if policymakers are unwilling to adopt these design features—or simply do not wish to reduce provider prices. I conclude that, without paying providers less, a public option likely could not set lower premiums than typical existing plans; its lower administrative costs and lack of a profit margin would likely be more than offset by disadvantages in utilization management, risk selection, and diagnosis coding. It might be able to offer lower premiums than existing plans that have broad networks and looser utilization controls, but at best only slightly lower. Thus, for this type of public option to create significant value, it would need to offer better coverage than existing plans (and convince consumers of that fact). A public option’s lack of a profit motive offers a reason it might offer better coverage, but far from a guarantee. In sum, while it is hard to envision this type of public option doing much harm, it also might not do much good.

The remainder of this analysis examines these issues in greater detail.[2]

Proof of Concept: Traditional Medicare

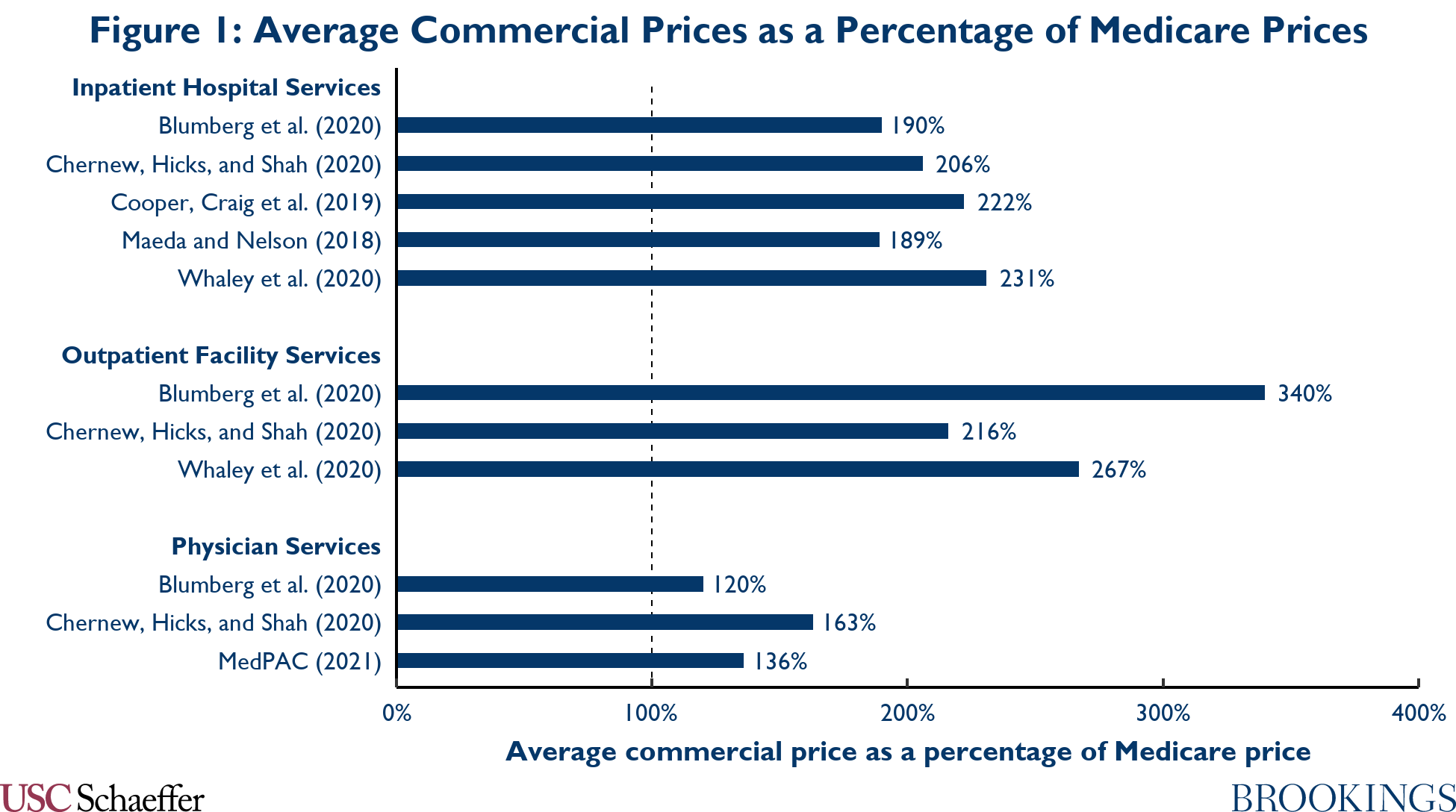

Experience from Medicare offers “proof of concept” that an insurance plan can pay providers much less than commercial insurers do and still elicit provider participation. Indeed, a broad literature, which is summarized in Figure 1, finds that commercial plans pay around twice what Medicare pays for inpatient hospital services. Commercial plans appear to pay even more in relation to Medicare for outpatient facility services. Differentials are smaller for physician services, but still substantial.

Despite the fact that Medicare pays much lower prices than commercial plans, Medicare beneficiaries have robust access to providers. Hospital and physician participation in Medicare is virtually universal, and surveys of Medicare beneficiaries find that they generally do not have difficulty finding a physician when

they need one (and experience levels of access similar to people with commercial plans). This likely reflects the fact that Medicare’s prices, while far below commercial prices, still exceed providers’ marginal cost of delivering care, which ensures that serving Medicare beneficiaries is profitable for health care providers. Indeed, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission estimates that Medicare’s prices exceeded hospitals’ marginal cost by 8% on average in 2019.

Designing a Public Option that Could Pay Lower Prices

The example of traditional Medicare suggests that it would be feasible for a public option to pay less than existing private plans while still attracting participation from providers. However, whether that occurred in practice would depend on how a public option was designed. I turn now to those design questions.

I begin by discussing a public option that would determine provider prices administratively, as Medicare does. I argue that this type of public option could pay less than existing private plans and still attract providers; however, this would only be true if providers that wanted to serve patients covered by the public option’s private competitors also had to serve the public option’s patients. I then turn to a public option that would negotiate prices with providers, like private plans; I argue that this type of public option would likely struggle to pay lower prices than existing private plans.

Public option with administered prices

Many public option proposals envision setting prices administratively, meaning that the public option would establish formulas that specify what it would pay for each service, often with adjustments for certain provider characteristics (e.g., the provider’s geographic location or teaching status). In practice, these types of public option proposals generally link the public option’s prices to Medicare’s prices.

The challenge for this type of public option would be attracting providers. In particular, providers who were paid more by existing private plans than by the public option would likely be reluctant to participate in the public option unless the public option had other tools to encourage participation. (A corollary is that a public option that lacked other tools for encouraging participation would primarily attract providers who it paid more than existing plans and, thus, pay providers more, on average, than existing plans with comparable networks.) While this conclusion is intuitive, it is worth being precise about why this would be true, as doing so can offer insight into how to solve the participation problem.

The core issue is that a provider’s decision to participate in the public option would reduce consumers’ demand for private plans—and particularly private plans that included that provider.[3] That, in turn, would reduce the premiums private plans could charge for plans that included the provider, thereby reducing private insurers’ eagerness to reach agreement with the provider and weakening the provider’s bargaining position. Of course, the provider would need to weigh these costs of participating in the public option against the profits it could earn by serving public option patients. But this tradeoff between gaining volume under the public option and weakening its bargaining position with other plans is fundamentally similar to the tradeoff providers face when negotiating with private plans today, so it follows that a provider would be unlikely to participate at prices well below what it received from existing plans.[4]

Policymakers would have a couple of options for solving this problem. One approach would be to require a provider to serve the public option’s patients if it wanted to serve patients covered by the public option’s private competitors (perhaps with exceptions for emergency care and certain other defined circumstances).[5] For example, a provider that refused to participate in an individual market public option might be barred from participating in private Marketplace plans.[6] This approach would eliminate the main benefit a provider obtains by opting out of the public option: the ability to extract higher prices from private plans. Thus, it would then be in the provider’s interest to serve the public option’s patients as long as the public option’s prices exceeded the provider’s marginal cost.[7]

Notably, the Medicare program includes rules like this. Institutional providers are required to accept Medicare patients on the same terms as they treat other patients, which would generally prevent providers from turning away traditional Medicare patients while treating Medicare Advantage patients.[8] These rules may be an important reason that provider participation in traditional Medicare is so broad, despite the presence of private Medicare Advantage plans. (The fact that Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in traditional Medicare program by default and that traditional Medicare has a large legacy market share may also play a role in allowing traditional Medicare to elicit broad provider participation.)

An alternative approach would be to directly require providers to participate in the public option. This type of requirement could be enforced by making participation in the public option a condition of participation in other federal coverage programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid, an approach that has been taken by at least one prominent public option proposal.[9] Alternatively, it could be enforced by freestanding fines on providers that declined to participate in the public option.

Public option with negotiated prices

I now turn to a public option that would determine prices through negotiations with providers, similar to how prices are determined in private insurance plans. The public option proposal passed by the House of Representatives during the 2009 health care reform debate took this basic approach, and some recent public option proposals would also determine prices through negotiations.[10]

However, there is little reason to expect that a public option could negotiate lower prices than private plans. Ultimately, an insurer’s only source of leverage in price negotiations is the threat to exclude a provider from its network if the provider refuses to agree to an acceptable rate. There is no clear reason to expect a public option to be better at wielding that threat than private plans and some reason to believe it would be worse since it might face political pressure to maintain a broad network.

A public option might be able to negotiate better prices if it had a source of leverage that private insurers lack. For example, if a provider that failed to reach agreement with the public option was also barred from serving patients covered by the public option’s private competitors, as suggested above, that could allow the public option to negotiate much lower prices. But for that leverage to be useful to the public option, the public option would need to be willing to use it. And there is reason to believe that it would be reluctant to do so in practice. In particular, the same political pressures that would tend to make a public option leery of excluding a provider from its own network would likely make the public option even more leery of excluding a provider from the individual market entirely.[11]

Negotiating prices with providers would also be administratively complex. There are about 6,000 hospitals in the United States and hundreds of thousands of physician practices.[12] Managing negotiations with all of those providers would be difficult and would cause the public option to incur meaningful administrative costs, forfeiting at least part of the administrative cost advantages a public option might otherwise hold (as discussed further below). In practice, the agency responsible for administering a public option could (and likely would) delegate that responsibility to a contractor, but it would then need to compensate the contractor. Creating appropriate incentives for a contractor could also be difficult.

Effects of a public option on prices negotiated by private plans

As an aside, I note that if a public option was successful in paying providers less than existing private plans while attracting broad provider participation, the public option’s private competitors would likely also become able to negotiate lower prices with providers. (A corollary is that private plans would likely be viable competitors for a public option that paid providers less than existing plans.)

In detail, faced with competition from the public option, private plans would recognize that they could not set premiums too far above the public option’s premium and still expect to attract enrollees. That, in turn, would make it unprofitable for insurers to pay providers prices too far above the public option’s prices, making insurers willing to walk away from negotiations with providers rather than pay prices that high. Providers, for their part, would recognize that if they failed to reach agreement with private plans, then their patients would enroll in the public option instead and they would be paid the public option’s prices, making it in their interest to agree to prices close to the public option’s prices.

Exactly where the prices paid by private plans landed would depend on how much competitive pressure the public option created, which would depend in turn on non-price determinants of the public option’s costs.[13] As I discuss in greater detail below, research comparing traditional Medicare to private Medicare Advantage plans suggests that a public option might manage utilization less aggressively, attract sicker enrollees, and be less aggressive in coding diagnoses under the individual market’s risk adjustment program (although it might also have somewhat lower administrative costs). Those factors would tend to raise the public option’s premium, reducing how much competitive pressure it placed on private plans and thereby allowing providers to negotiate prices somewhat above the public option’s prices.

The notion that the presence of a public plan could constrain the prices that private plans paid providers is not just theoretical. A striking feature of the Medicare program is that private Medicare Advantage plans pay physicians and hospitals prices that closely mirror traditional Medicare’s prices. There is some debate over whether this primarily reflects the effects of competitive pressure from traditional Medicare or the fact that the amounts providers can collect for out-of-network care delivered to Medicare Advantage enrollees are capped at traditional Medicare’s prices. However, I have argued elsewhere that unless providers are compelled to accept an insurer’s patients (which they generally are not outside of emergency situations), the scope for an out-of-network cap to reduce negotiated prices is likely relatively limited. If that is true, then it suggests that competition from traditional Medicare plays the lead role in explaining why Medicare Advantage plans negotiate prices so close to traditional Medicare’s.

Finally, I note that the introduction of a public option that reduced provider prices could also change what types of plans consumers held. When the overall level of provider prices is lower, private plans are likely to have less scope to use narrow networks to negotiate lower prices. Similarly, when unit prices are lower, plan efforts to reduce utilization will tend to generate smaller reductions in claims spending. This suggests that introducing a public option that paid providers less would tend to reduce the premium advantage held by narrow network and tightly managed plans, which would likely cause consumers to migrate toward broader network, less tightly managed plans (whether they be private or public).

Rationales for Creating a Public Option Other than Reducing Provider Prices

In practice, policymakers might not be willing to design a public option in a way that would make it effective in reducing prices—or might not even have the goal of reducing prices in the first place. In that case, a natural question is whether there is still a rationale for creating a public option.

This section considers two potential alternative rationales. First, a public option might offer consumers lower premiums by virtue of incurring lower administrative costs or eschewing profits. Second, because a public option would lack a profit motive, it might offer better coverage. I discuss each rationale in turn and conclude that neither is compelling, although neither can be completely dismissed.

Before proceeding, I note that creating a public option that paid providers prices similar to the prices paid by existing private plans would be easier said than done. As described above, if a public option negotiated prices with providers, it might well end up paying providers more than existing private plans.

Setting prices administratively would be challenging too. The entity administering the public option would need comprehensive, granular data on the prices paid by private plans, which do not currently exist. Additionally, the prices paid by the public option would likely need to vary across providers in ways that mirrored how prices vary in private plans, which could be difficult to achieve; if a public option failed to do so, it would disproportionately attract providers that it paid more than private plans and potentially pay higher average prices than private plans with comparable provider networks. Another complication is that providers might recognize that agreeing to a lower price with a private insurer could reduce what they were paid by the public option, leading providers to demand higher prices from private plans than they do today.[14] I do not discuss these issues further, but policymakers interested in implementing a public option that paid prices similar to existing private plans would need to grapple with them.

Lower premiums

A common argument in favor of a public option is that it could set lower premiums by virtue of incurring lower administrative costs or eschewing profits. I consider each potential source of savings in turn:

- Administrative costs: In prior work, I used the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) data to estimate that private insurance plans incurred administrative expenses of $482 per enrollee (9.3% of premiums) in 2018. For comparison, Medicare’s cost of administering Parts A and B of Medicare was $229 per enrollee, about half as large.

As discussed in that earlier paper, Medicare’s per enrollee costs are not a perfect guide to the administrative costs a public option would incur. Notably, a public option’s enrollees would be younger and presumably need less care, so per enrollee claims processing expenses would likely be lower. On the other hand, the Medicare figure cited above does not include costs of administering a prescription drug benefit, so a public option’s costs could be higher.

Nevertheless, the large disparity suggests that a public option would indeed incur lower administrative spending than existing private plans, at least if it was patterned after traditional Medicare. That might plausibly reflect economies of scale from relying on Medicare’s infrastructure, as well as that fact that a public option would likely take a less aggressive approach to utilization management, diagnosis coding, and risk selection, as discussed further below.

- Profit margins: Public option proposals generally envision that a public option would set premiums that covered its costs but did not incorporate a profit margin. The importance of this difference from private plans depends on the size of the margins earned by private plans.

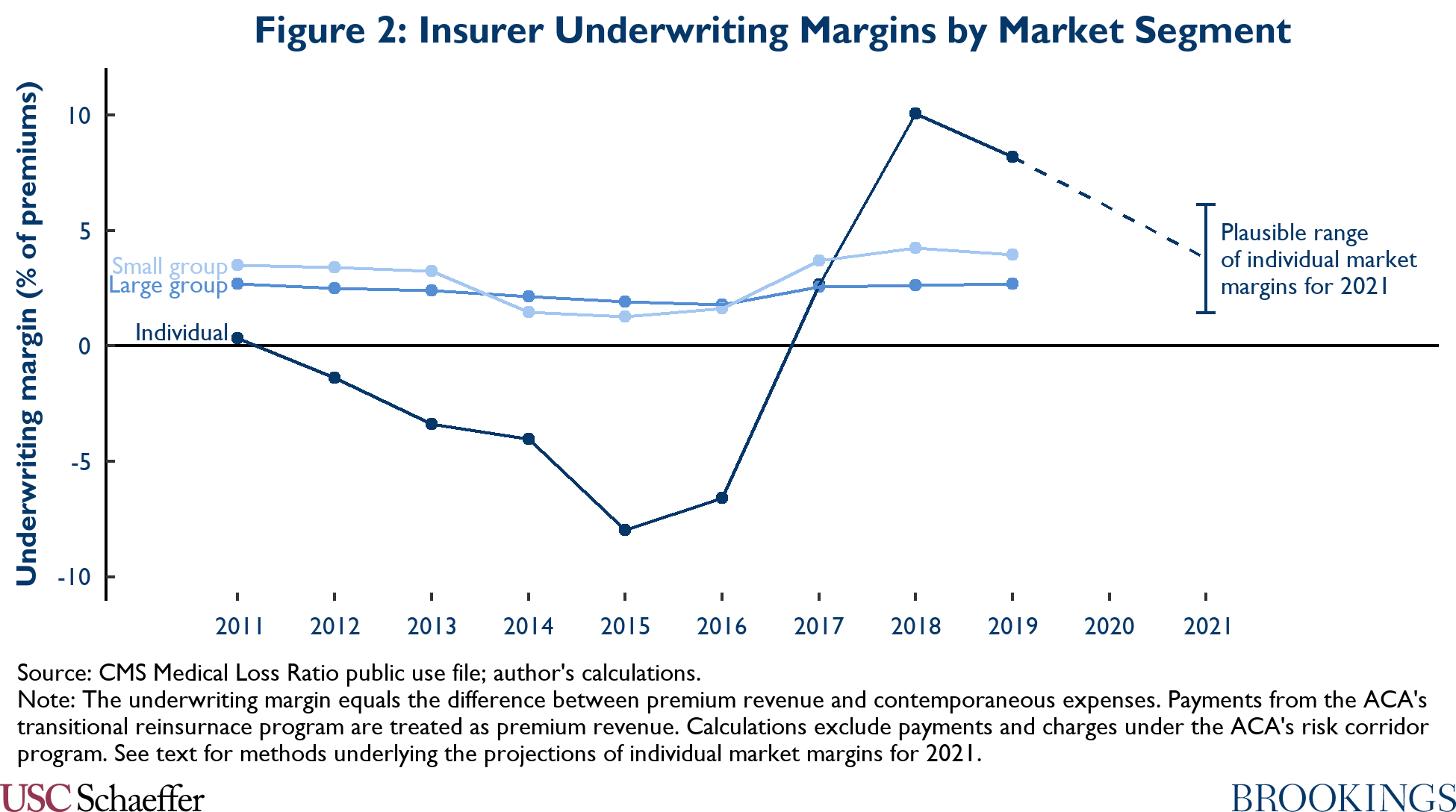

To provide insight on that question, Figure 2 plots insurers’ underwriting margins for 2011 through 2019, as estimated in the MLR data.[15] A clear challenge in forecasting future individual market margins is that they have been highly volatile in recent years, likely because of the rapidly changing policy environment. Insurers incurred losses in the years before implementation of the ACA’s main reforms in 2014, but those losses deepened dramatically thereafter, likely primarily because insurers misjudged the post-ACA risk pool. Insurers returned to profitability in 2017 following large premium increases. Margins then surged in 2018 and 2019 as insurers reacted to (and, as it turned out, overreacted to) various Trump administration policy changes.

By contrast, margins in the small and large group markets—where policy has been relatively stable—have fluctuated in a narrow range over this period, centered on an average of 2.9% in the case of the small group market and an average of 2.4% in the case of the large group market.

Additionally, individual market margins appear to be on track to return to the low-to-mid single-digits in 2021.[16] The average Marketplace premium has fallen by 2.2% from 2019 through 2021, likely driven at least in part by insurer entry.[17] Gauging how insurers’ expenses evolved from 2019 to 2021 (and, more to the point, how insurers expected them to evolve when setting 2021 premiums) is harder given the uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, Figure 2 presents a range of plausible margins corresponding to a range of assumptions about expenses.

The top of the range corresponds to a scenario in which insurers’ nominal per enrollee expenses in 2021 equal their 2019 level, which may be roughly where expenses stood when insurers finalized their rates in mid-to-late 2020.[18] This scenario is one in which the COVID-19 pandemic continues to place substantial downward pressure on health care utilization throughout 2021, as it did during much of 2020; it yields a margin of 6.1% of premiums. The bottom of the range corresponds to a scenario in which nominal per enrollee expenses in 2021 are 5% higher than in 2019, which is roughly what would happen if expenses returned gradually to their pre-COVID trend during 2021; this scenario yields a projected margin of 1.4% of premiums.

Taken together, the recent history of margins in the small and large group markets and the fact that individual market margins appear on track to return to the low-to-mid single-digits this year suggests that it is reasonable to expect individual market margins to settle in the low single-digits over the medium run. However, the outlook may become clearer with more years of data.

If lower administrative costs and the lack of a profit margin were the only differences between a public option and private plans, then the preceding discussion suggests that a public option that paid providers prices comparable to existing plans would likely charge lower premiums than existing plans, perhaps by mid-to-high single-digit percentages. However, research that has compared traditional Medicare (the model for most public option proposals) to private Medicare Advantage plans suggests that a public option would have higher costs than private plans along several other dimensions:

- Utilization: Holding enrollees characteristics fixed, enrollees appear to use more health care when enrolled in traditional Medicare than when enrolled in Medicare Advantage, presumably because Medicare Advantage plans manage utilization more aggressively. For example, Curto and colleagues estimate that a person enrolled in traditional Medicare uses 9% more services than an otherwise identical person enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan.

- Risk selection: Traditional Medicare also seems to be preferred by enrollees who have greater health care needs. Estimates of the extent of selection vary, but Curto and colleagues’ estimates imply that traditional Medicare enrollees’ claims risk was about 6% higher than the Medicare population as a whole, even after adjusting for characteristics included in risk adjustment.[19].

- Diagnosis coding: A wealth of evidence demonstrates that Medicare Advantage plans are more aggressive in coding enrollees’ diagnoses. Using a particularly compelling methodology, Geruso and Layton estimate that Medicare Advantage plans’ more aggressive diagnosis coding makes enrollees look 6% sicker than identical traditional Medicare enrollees. In Medicare Advantage, a portion of private plans’ aggressive coding is offset by a “coding intensity adjustment” that reduces private plans’ risk scores. In principle, policymakers could do something similar for an individual market public option, although existing public option proposals generally do not.

Taken together, utilization, risk selection, and diagnosis coding differences like these would be more than enough to offset the public option’s lower administrative costs and lack of a profit margin. And it is conceivable that the utilization and risk selection differences between an individual market public option and its private competitors could be larger than the differences between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans since many existing individual market plans have narrow networks and tight utilization controls. Thus, a public option that paid providers prices similar to existing plans would likely charge higher premiums—and perhaps much higher premiums—than typical existing plans.

This type of public option might be able to offer lower premiums than existing plans that have broad networks or looser utilization controls. A public option would likely have smaller disadvantages in utilization and risk selection relative to these plans, although it might also have smaller administrative cost advantages. Thus, relative to these plans, a public option’s lower administrative costs and lack of a profit margin might outweigh its cost disadvantages, particularly if policymakers created a coding intensity adjustment that offset part of private plans’ diagnosis coding disadvantages. However, it seems likely that any premium advantage a public option did hold relative to these plans would be relatively small.

As a final note, if the public option’s premiums were close enough to private plans’ premiums that the public option did attract non-trivial enrollment, it could modestly reduce the premiums of private plans. First, it might place some competitive pressure on those plans, causing them to set premiums that incorporated lower profit margins. Second, the public option’s coding disadvantages could cause it to make risk adjustment payments to private plans, which might reduce private plans’ premiums. Third, advantageous selection might also reduce private plans’ premiums, although this is less clear; while selection would clearly make the average private plan enrollee healthier, it might not make the marginal enrollee healthier, and it is the marginal enrollee that governs private plans’ premium-setting incentives.

Better coverage

A different rationale for creating a public option is that it would offer better coverage. By virtue of lacking a profit motive, a public option might be less motivated to reduce its claims spending and thus might eschew cost-sharing, network, or utilization management practices that discourage receipt of appropriate care or expose enrollees to excessive financial risk. Of course, private insurers face competitive pressure to avoid these practices. But this is true only to the extent that consumers can observe these practices, which not always be the case, particularly given the complexity of health insurance products.

There is some empirical evidence consistent with the view that a public option would better serve its enrollees’ interests. Indeed, some of the additional utilization that occurs in traditional Medicare relative to private Medicare Advantage plans appears to be high-value care. However, this evidence is far from definitive. Tighter utilization controls might unavoidably discourage some mix of low- and high-value care, and enrollees might be willing to accept that tradeoff in exchange for lower premiums or other benefits, so this pattern could arise even if Medicare Advantage plans were acting in accord with enrollees’ wishes.

Even if a public option did offer better coverage, consumers would only benefit if the public option attracted substantial enrollment. A public option that paid providers prices similar to existing plans might struggle to do so. As described in the last section, this type of public option would likely set higher premiums than most existing plans. While it might set slightly lower premiums than existing plans with broad networks and looser utilization controls, those types of plans currently play a marginal role in the individual market, presumably because individual market consumers are not willing to pay the higher premiums those plans charge. Thus, for this type of public option to attract meaningful enrollment, consumers would likely need to be willing to pay much more for a public option than for private plans.

It is certainly conceivable that consumers would be willing to pay more for a public option. In particular, a public option’s differing incentives and governance might allow it to elicit greater trust from consumers. That might make consumers more confident that a public option would provide good coverage and, thus, willing to pay higher premiums. As an empirical matter, the fact that traditional Medicare retains a majority of Medicare beneficiaries even though Medicare Advantage plans offer lower premiums and supplemental benefits is consistent with the view that consumers look more favorably on public plans. But there are other factors that could also account for traditional Medicare’s market share (e.g., Medicare Advantage plans’ narrower networks and the fact that traditional Medicare is the default enrollment choice), and it is far from clear that individual market consumers would have similar attitudes.

As a final note, while a public option might offer better coverage in some respects, it could offer worse coverage in others. Most importantly, a public option might be less nimble than private plans and take longer to cover new types of care, particularly if doing so required a statutory change. Indeed, the fact that prescription drug coverage had become essentially universal in employer-sponsored insurance plans by the time Medicare added a prescription drug benefit offers a cautionary tale.

Conclusion

This piece has argued that a public option could pay providers less than existing private plans while still attracting providers as long as it had two features: (1) the public option set prices administratively; and (2) providers could not serve patients covered by the public option’s private competitors without also serving the public option’s patients. A public option that had these features would likely also create competitive pressure that would substantially reduce the prices paid by private plans.

If policymakers are not willing to adopt these design features (or are simply not interested in reducing provider prices), then the rationale for creating a public option is less clear. A public option that paid prices comparable to existing plans would likely set higher premiums than most existing plans. Even relative to existing plans with broad networks and looser utilization controls, this type of public option would at best offer slightly lower premiums. Thus, a public option’s only real way to add value would be to offer better coverage (and convince consumers of that fact). This is possible, but by no means certain.

In closing, I note that this piece does not address the question of whether policymakers should seek to implement a public option that paid lower prices. Reductions in providers’ revenues could make some providers unable to cover their fixed costs, forcing them to cut costs or exit the market, either of which could have negative consequences for patient care. Providers might also have weaker incentives to invest in improving quality since attracting additional patients would now be less lucrative and since higher quality would be less likely to be rewarded with higher prices when prices are set administratively. Lower prices would also, naturally, tend to result in lower incomes for health care providers.

Those potential downsides would need to weighed against the savings generated by a public option—and what those savings could finance. Policymakers might reasonably be willing to tolerate some risk of negatively affecting care delivery if implementing a public option saved money for consumers, facilitated expanding insurance coverage, or had some other beneficial effect. Additionally, to the extent that the savings from a public option were used to finance expanded insurance coverage, that would tend to offset some of the financial pressure a public option placed on providers, thereby reducing the risk that a public option would have ill effects on care delivery in the first place.

Footnotes:

[1] Some proposals also allow employers to purchase coverage through the public option on behalf of their workers. Those proposals are not the focus of this piece, although many of the main considerations are similar.

[2] I discuss the design and effects of a public option, as well as other tools for reducing provider prices, at greater length in another recent paper.

[3] A provider might also decline to participate in the public option if the public option paid prices below the provider’s marginal cost. However, the broad provider access enjoyed by Medicare beneficiaries suggests that such providers would be relatively rare as long as the public option paid providers at least as much as Medicare does, which essentially all prominent public option proposals do.

[4] There is a caveat. Unlike when a provider negotiates with a private insurer, a provider could not hope to “hold out” to get a better price from a public option that sets prices administratively. In essence, the public option would be able to make a “take-it-or-leave-it” offer to providers. That might allow the public option to attract providers at modestly lower prices than existing private plans, but likely not dramatically lower prices.

[5] Note that merely requiring providers to “participate” in the public option would not be good enough. Providers would need to be required to give public option patients meaningful access to their services. My earlier paper discusses how those types of requirements could be structured in greater detail.

[6] In principle, this could be structured as a requirement on insurers rather than providers. That is, insurers could be barred from covering services delivered by providers that did not serve public option patients.

[7] On the other hand, this could lead some providers with marginal cost above the public option’s prices to stop serving the individual market altogether since they would have little hope of negotiating higher prices with private plans without being able to offer private plans preferential access to their services. In any case, the example of Medicare suggests the number of providers in this category would likely be small, at least as long as the public option paid providers prices at least as high as Medicare’s.

[8] See 42 CFR § 489.53(a)(2).

[9] A potential concern with the latter approach is that providers might opt out of Medicare and Medicaid rather than comply with the requirement to participate in the public option. That is likely not a substantial risk in the case of an individual market public option since forgoing all Medicare and Medicaid volume would be too high a price to pay to protect their margins in the relatively small individual market.

[10] Some proposals place bounds on the prices the public option is permitted to negotiate. In practice, proposals like these might end up resembling a public option that set administered prices equal to the upper bound.

[11] A public option could likely also do better than private plans if providers were literally required to participate in the public option since the public option could then set prices by fiat. But a public option could do better in this setting precisely because prices would, in effect, be administered, not negotiated.

[12] There are approximately 1 million licensed physicians in the United States. The American Medical Association’s 2018 Benchmark Survey found that about 15% were in solo practice (suggesting there are around 150,000 solo practices), and another 20% are in practices with 2-4 physicians (contributing at least another 50,000 practices).

[13] My earlier paper provides quantitative simulations of how these factors would affect outcomes.

[14] A similar problem may arise under the Medicaid drug rebate program, which generally requires drug manufacturers to offer state Medicaid programs the best price it offers any payer. One solution to this problem would be to determine what the public option paid providers based on what private plans paid before the public option was created. A problem with this solution is that these prices might get “stale” over time.

[15] I note that the estimates in Figure 2 are estimates of contemporaneous accounting profits that omit the costs of capital investments made in prior years, so true economic profits could be smaller. Indeed, in a competitive market with free entry, economic profits would be expected to be zero. In practice, however, private insurers appear to wield some market power, so it is likely that at least a portion of observed margins represent economic profits. Additionally, insurers do have incentives to understate their premium revenue and overstate their claims costs in these data to avoid paying MLR rebates, which could cause these data to understate profit margins.

[16] On the other hand, 2020 will likely be another year of high margins, primarily because the COVID-19 pandemic led to large reductions in utilization of non-urgent care, which substantially depressed claims spending.

[17] This estimate was calculated using the Marketplace open enrollment public use files and holds the distribution of enrollment by state and metal level fixed from 2019 to 2021. The calculation only includes states that used the HealthCare.gov enrollment platform in both years.

[18] Data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis indicate that nominal health care spending per capita was about 0.5% below its 2019 average level as of September 2020.

[19] In detail, Curto and colleagues. report that average per member per month spending in traditional Medicare is $855 (in the geographic areas they examine), after adjusting for individual characteristics accounted for in risk adjustment. In analyses that attempt to adjust for a broader set of health status characteristics, that estimate falls to $706 per member per month. In other work, I have estimated that Medicare Advantage plans accounted for 30% of total Medicare enrollment in the states and year the authors examined. This suggests that the claims risk of traditional Medicare enrollees was about 6% (=1/[0.7+0.3*706/855]-1) higher than the Medicare population as a whole. There have likely been improvements in risk adjustment since the years the authors examine (2010), so differences could be smaller today, although plans could also have gotten better at risk selection over time.

Acknowledgments:

I thank Loren Adler and Paul Ginsburg for helpful comments on a draft of this piece. I thank Conrad Milhaupt for excellent research assistance, and Brieanna Nicker for excellent editorial assistance. All errors are my own.