TIME

Middle-class incomes have risen painfully slowly in recent decades, as we showed in the last chapter. The modest improvements that have occurred largely result from an increase in the employment and earnings of women. That, in turn, has created what we call “a time squeeze.” Americans are working more than adults in other advanced countries, often face unpredictable work schedules, must cope with school hours that are badly aligned with working hours, and get little help with caring for children or the elderly. Half of all American adults say they do not have enough time to do what they want with their days.

Incomes can grow; time cannot.

Of course, everybody is different. Some people love their work and have no desire for more leisure. Others dislike what they do and would prefer not to work at all. Probably most of us are somewhere in between these two extremes. So personal choice is important. As we argued above, work is also highly valued in American culture and many people with good jobs work long hours out of choice. That is a fact that we celebrate. The idea of a “leisure society” is distinctly unappealing – and frankly un-American.

But it is also the case that current norms around the definition of “full-time” work are outdated. They do not provide people with much choice or flexibility. And well-being seems to be higher in countries where people work a little less. Helping middle-class families have more time for themselves and their families is therefore an important goal for public policy.

The time squeeze

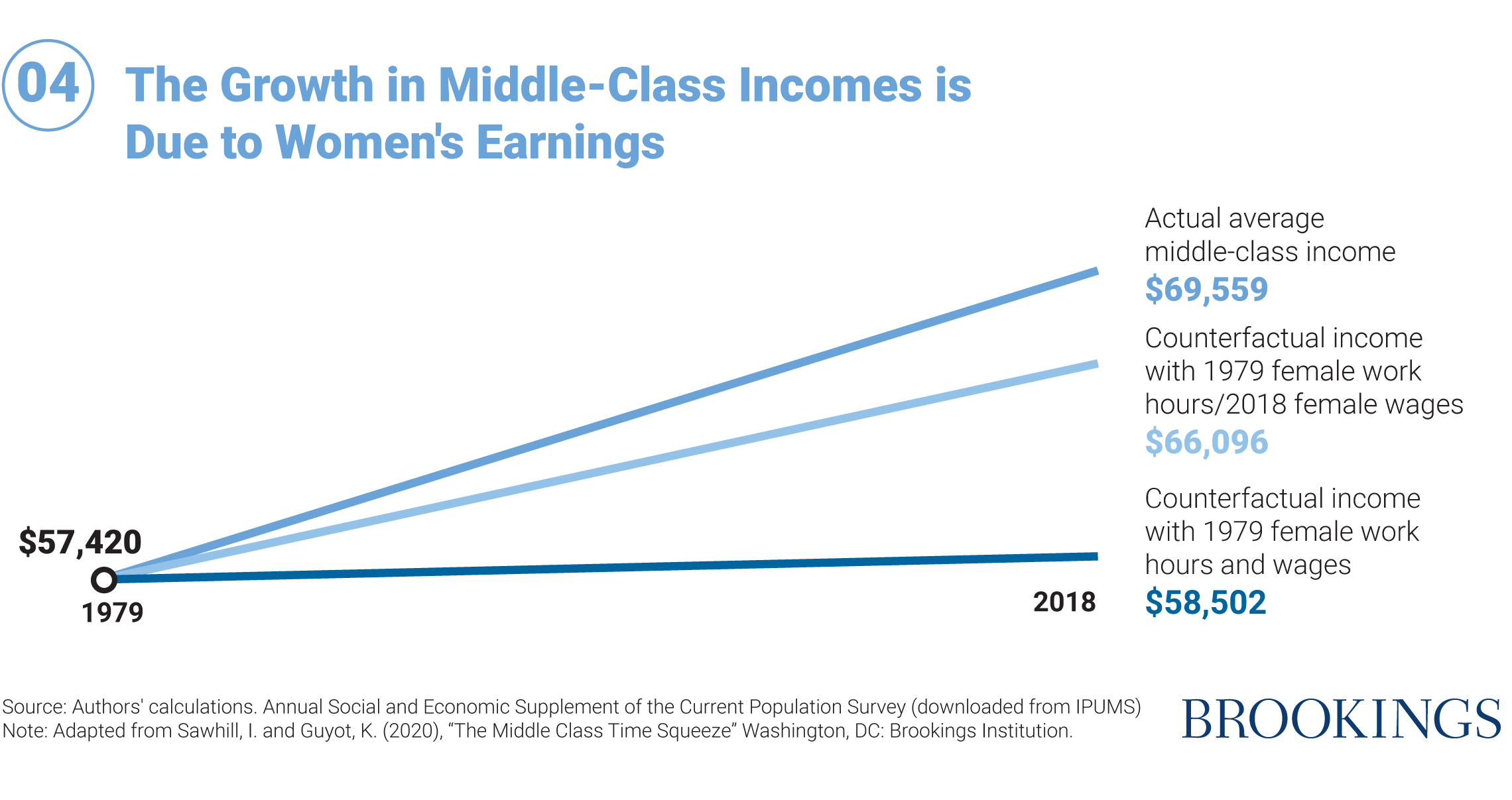

In 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that within a century, economic growth would cut the typical work week to 15 hours. This has not happened – especially in the U.S. The average middle-class married couple with children now works a combined 3,446 hours per year. This is 600 hours – or a day and a half per week – more than in 1975. This reflects the increase in women’s employment, which has been economically essential to middle-class families. In fact, if women’s employment and especially wage levels had not increased, middle-class households would have experienced virtually no income growth at all (Figure 4).

Although female employment has been hit hardest by COVID-19, women still hold half of all payroll jobs in the economy. Over 40 percent of mothers are the sole or primary breadwinner; most couples (70 percent) are now dual earners. The result is greater time pressure on families. “The shift from American Wife to Family (co-) Breadwinner has left a gap at home,” writes the economist Heather Boushey. “Who’s caring for the children and teaching them all they need to know? Who’s tending to an aging family member who needs some extra care?”

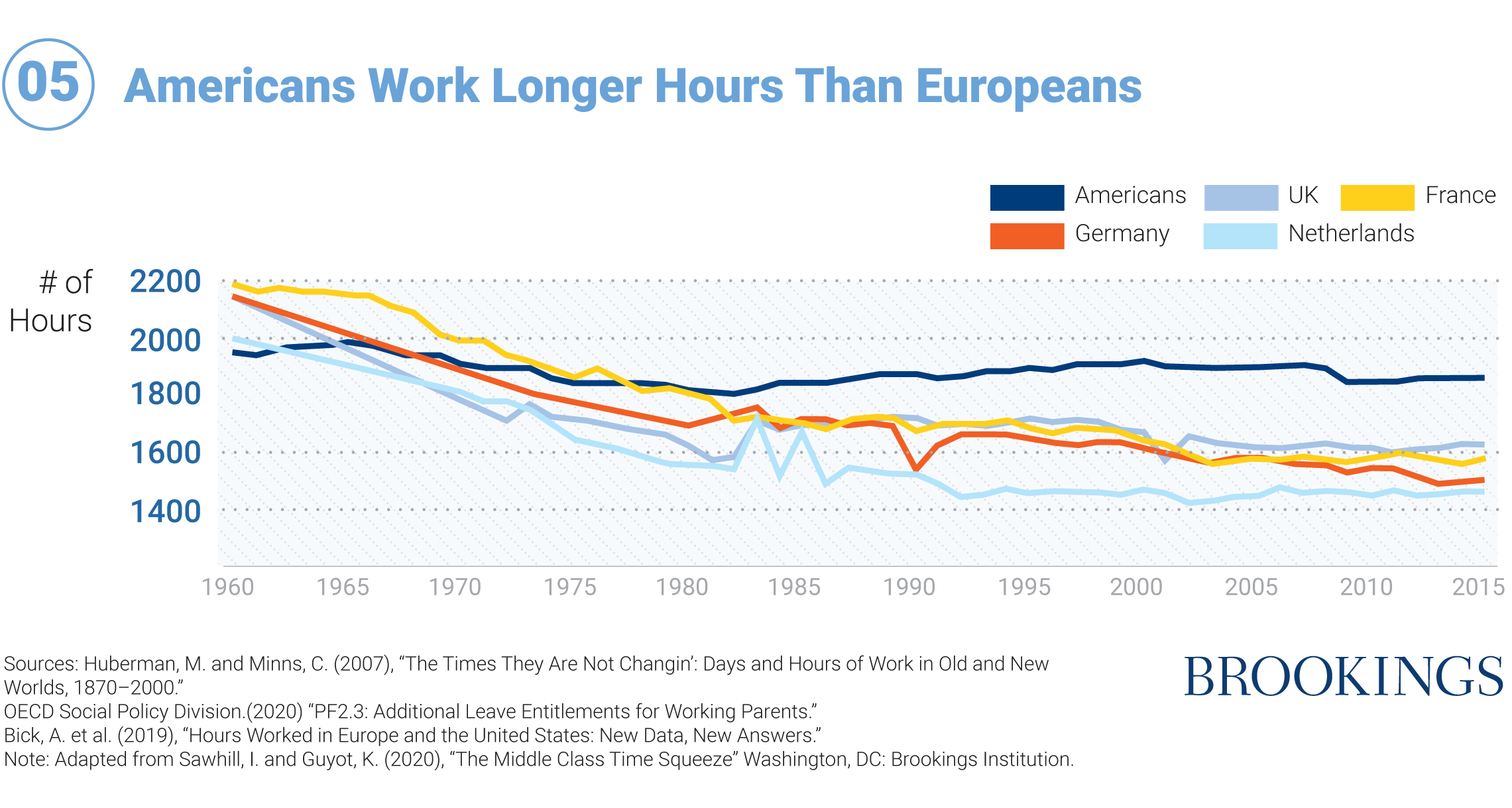

The U.S. now stands out among similar nations in terms of more working hours. The average American worker now spends 200 to 400 more hours at work over the course of the year than the average worker in most European countries – the equivalent of an extra 4 to 8 hours per week (Figure 5).

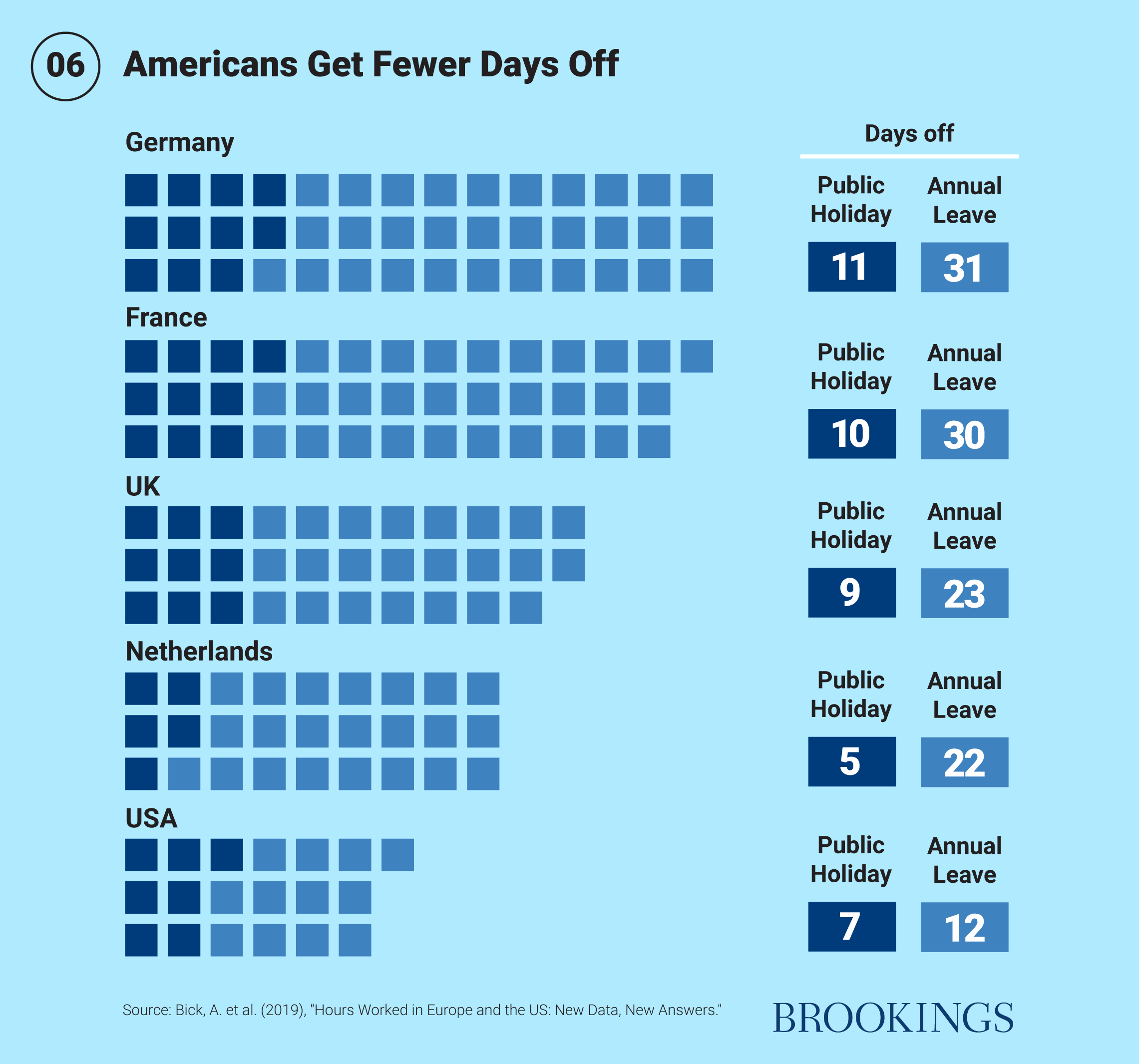

Why do Americans work so many more hours each year than Europeans? Most of the gap results from differences in the number of weeks worked per year, rather than the length of the work week. This in turn reflects differences in legal rights to leave and holidays. The fact that the U.S. has no mandated leave at all (beyond some holidays) is the primary source of the gap; Germany provides twice as much time off as the U.S. (Figure 6). Policy matters.

The distribution of work across the lifecycle is important, too. Longer periods of education and retirement have caused a decline in employment rates in the early and later years of adult life. Even as lifespans have increased, paid work has become more concentrated in the middle years of adulthood – which are also the years when most people are raising children. We have some groups, then, who are experiencing a time squeeze and others a time surplus. Mothers face particularly acute time pressure. Working time could be allocated more fairly and efficiently across the life cycle, as well as between families with children and those without, and between men and women.

To help middle-class Americans have more time, and to ease the time squeeze, we propose a legal right to a minimum of 20 days leave each year; mid-career “sabbaticals” for retraining or care work; and aligning school schedules with jobs.

Twenty days of paid leave

One way to reduce working time is to require all employers to provide a certain amount of paid personal time off for all employees. The U.S., as we have seen, is the only advanced country that does not do this. The reasons for taking leave vary enormously – for illness, vacation, the birth of a baby, to care for an elder. We therefore propose a broad rather than categorical entitlement, to 20 days per year of paid leave. This is less than many other countries but would at least establish a minimum floor. Some employers already provide this much paid leave in one form or another. But many do not – especially for their low-wage workers. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for such leave should be obvious. Part of the new contract with the middle class should be: if you are sick, you must stay home. But we will pay you to do so.

I work the first shift. My wife works the third shift… We barely see each other.

Factory Worker & Father, Lebanon, PA

Mid-career sabbaticals

One role of social insurance is to distribute income across our lifetimes. Most obviously, taxes paid while we are earning help to fund our pension and health care in retirement. But social insurance is also about the distribution of time and is increasingly out of kilter with modern needs. The rise of dual-earning couples and increasing life expectancy causes a time imbalance; workers face considerable mid-life time pressure but have greater disposable time in later life.

We therefore propose a new social insurance benefit to cover mid-career time off for care work or retraining. Specifically, this would mean:

- Two new accounts within the existing Social Security system: one for lifelong learning and one for paid family leave.

- The lifelong learning account could be used for living expenses as well as tuition for an approved program of education or training to upgrade skills, in order to relocate to a new area, or to start a new business.

- The paid leave account could be used for family care, including the birth of a child, an extended illness, or for the care of a relative. It would be linked to wages (up to a certain limit) and cover up to 12 weeks of leave. It could be used in combination with the 20 days of general paid leave.

Schooldays matching workdays

The middle class is not just working long hours; many also face unpredictable schedules set by employers, little or no flexibility about when they must be at work, inadequate child care, and school schedules that are poorly aligned with existing work hours. While the most common work schedule is 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., the most common school schedule is 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. The misalignment of school schedules costs the U.S. more than $50 billion a year as parents are forced to reduce their work hours or stay home.

The average start time for middle and high schools is around 8 a.m. We propose that the standard school day be shifted later to better align with most job schedules, and that after-school care be made universally available. A later start time would also be good for students, especially those in high school. Specifically:

- After-school care would be universally available to students at public elementary and middle schools, enabling most parents to pick their children up from school around 5:30 or 6 in the evening.

- The federal or state government would provide grants to local education agencies that agreed to change their hours and provide an extended school day or school year.

- Participation in the extended hours would be optional for students and their families.

- To contain costs, families would pay on a sliding fee scale.

- School districts could decide how to use the additional hours, whether for additional instructional time or for extracurricular activities.

- For younger children, universal pre-k programs and subsidized child care should play a similar role. State pre-k programs have expanded in recent decades, especially for four-year-olds, but many states limit access to poor children, or do not serve three-year-olds. The evidence on whether such programs improve later school performance is mixed, but there is no doubt that they play an important role in easing the time squeeze for middle-class families.

- To fill remaining child care gaps, and provide flexibility, we also recommend making the existing child care tax credit both more generous and completely refundable.

There are many other policies that ought to be pursued to ease the time squeeze, including giving workers more control over their hours. Workers who are subject to unpredictable schedules experience more material hardship, less financial security, and score lower on measures of well-being, such as happiness and sleep quality, while experiencing more psychological distress. Jobs used to help organize time: now, with the rise of just-in-time scheduling and zero-hours contracts, they often “disorganize” time as Mark Fabian, an economist at the University of Cambridge, puts it.

I never have enough time… I feel like there needs to be three of me.

Working Mother of Four, Wichita, KS

There is also significant scope for more remote working, as the COVID-19 pandemic has vividly demonstrated. As we write, half of America’s workers are working from home – a tenfold increase on the usual number. The benefits are significant. In our interviews with middle-class families, the value of remote work, especially for balancing work and parenting, is clear. In addition, commuting is one of the most disliked activities that people perform on a daily basis. The average two-way commute takes about an hour out of a worker’s day, and has been increasing since 1980. Although commuting often provides access to cheaper housing, better education, and other amenities, it is associated with higher levels of fatigue and stress and greater absenteeism. It is also bad for the environment. Once the pandemic recedes, these lessons must not be lost. We recommend more experimentation by businesses and other organizations, with careful evaluation of the costs and benefits.

Time ≠ money

Too many middle-class Americans face a stark choice between a money squeeze and a time squeeze. More time at work means more stress at home, poorer mental health, and less civic engagement. Thoughtful policy can help to restore some balance.

To be clear: a reduction in working time could result in slightly lower levels of economic activity. But if growth was all that mattered, we should all be working 80 hours a week. Families need income, but they also need time. More time should mean less stress, better health, and more time for our relationships – which we turn to next.

Special thanks to Katie Guyot and Morgan Welch for their research support.

America can only be as strong as the American middle class. We believe that the new contract we have described here, based on the core principles of partnership, prevention, and pluralism, holds out the promise of a better future for the middle class — and therefore for the nation. Let us know what you think.