INTRODUCTION

The U.S. is a middle-class nation. Since our nation’s founding, the American Dream has always been based on an implicit understanding – a contract if you will – between individuals willing to work and contribute, and a society willing to support those in need and to break down the barriers in front of them.

An aristocratic leisure class and a welfare-dependent underclass are equally unappealing to most Americans. This is why most people say they belong to the middle class. It is also why paid work is seen as so important. Americans – above all the newest among us, immigrants – want a society where everybody has the chance to “make something of themselves.”

Today, this contract is collapsing. Middle class families are working harder, with too little to show for it. Confidence in the prospects for the next generation is low. Trust in our institutions, and even in each other, is declining. The gaps between us are widening. Populism, fueled in part by middle class discontent, is rising.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been like the flash of an X-ray, exposing the deep fractures in our society – not least by race, but also by social class and economic status. Well-educated professionals, secure in their jobs and safe in their homes, have been observers of the devastation all around them. Meanwhile, the fragile finances, poor health and precarious employment of middle-class Americans, including many essential workers, have been laid bare.

A new contract with the middle class must be faithful to the spirit of our history but oriented towards the challenges of today’s economy and society. It should ask more of government as well as of Americans. A better future for the middle class is no longer just an important aspiration. It is an existential necessity.

Partnership, prevention, pluralism

Note that the new contact is with the middle class, not for the middle class. Middle class Americans are not inert vessels, waiting to be filled up with good things by a benign state. They want agency over their own lives. The first principle underpinning this contract, then, is partnership. College should be free (for at least two years), but only for those who undertake a year of national service: Scholarships for Service. Incomes should be higher, especially for those who are working. Health care should be better, but we each need to take more responsibility for our health, too. More time should be available to parents, but we should be willing to work until later ages.

The second principle is prevention. Too often public policy is focused on dealing with the costs and consequences of earlier failures – providing ambulances at the bottom of a cliff, rather than building fences at the top. It’s far better to act early. This means investing in health rather than health care, for example by improving nutrition or social services. It means universal access to reproductive health, especially the most effective forms of contraception, in order to give every child a strong start, ideally with two committed parents. It means providing childcare and working arrangements to prevent parents and (especially) mothers from losing ground in the labor market.

The third principle is pluralism. America is a large, varied, changing society. Individuals and communities differ, often greatly, in terms of what they want from life. This kaleidoscopic diversity is one of our greatest strengths. As far as possible, policy should embrace and even encourage a plurality of opinions, approaches, and goals. One size rarely fits all. National service ought to be a universal norm – but its form and organization will vary greatly. Our democratic processes should be inclusive of a wide range of voices – for example through “Citizens Juries” to guide policy. Families can come in all shapes and sizes and should be entitled to equal treatment. The ability to respect others, across lines of class, race, and politics, is a necessary skill in a diverse republic.

Who is middle class?

The central goal of our Future of the Middle Class Initiative at Brookings is to “improve the quality of life of America’s middle class.” Some definitions are needed here. Who is middle class? As we’ve already said, most Americans define themselves that way. But we define the middle class as those in the middle 60% of the household income distribution – not poor, but not prosperous either. The average middle-class household has about $70,000 in income after taxes and transfers. To be middle class, a household of three would have an income between $40,000 and $154,000.

Many of the policies we argue for here will help a broader swath of American society – but the overall package is designed to help the middle class the most. We were particularly concerned not to promote policies that could worsen the position of those in the bottom fifth of the distribution. The goal was to help the middle class without hurting the poor. We also focus largely on working-age adults. This should not be read as a lack of concern for either children or older people. In both cases there is an urgent need for policy reforms. But since most children are raised by working-age adults, and almost all retirees are former workers, the working-age years are the critical ones in terms of family life and preparing for retirement.

One final matter of definition needs to be addressed. The term “middle class” (or “working class,” for that matter) is often used as a racially-coded, exclusionary term, with an implicit prefix: white. This is ethically wrong and empirically false. The middle class, by our definition, is diverse: 59 percent white, 12 percent Black, 18 percent Hispanic, and 6 percent Asian. Within a few decades, whites will make up the minority of middle-class families. It is especially important to acknowledge, then, that middle-class Americans of color face additional challenges in the achievement of many of the goals set out here.

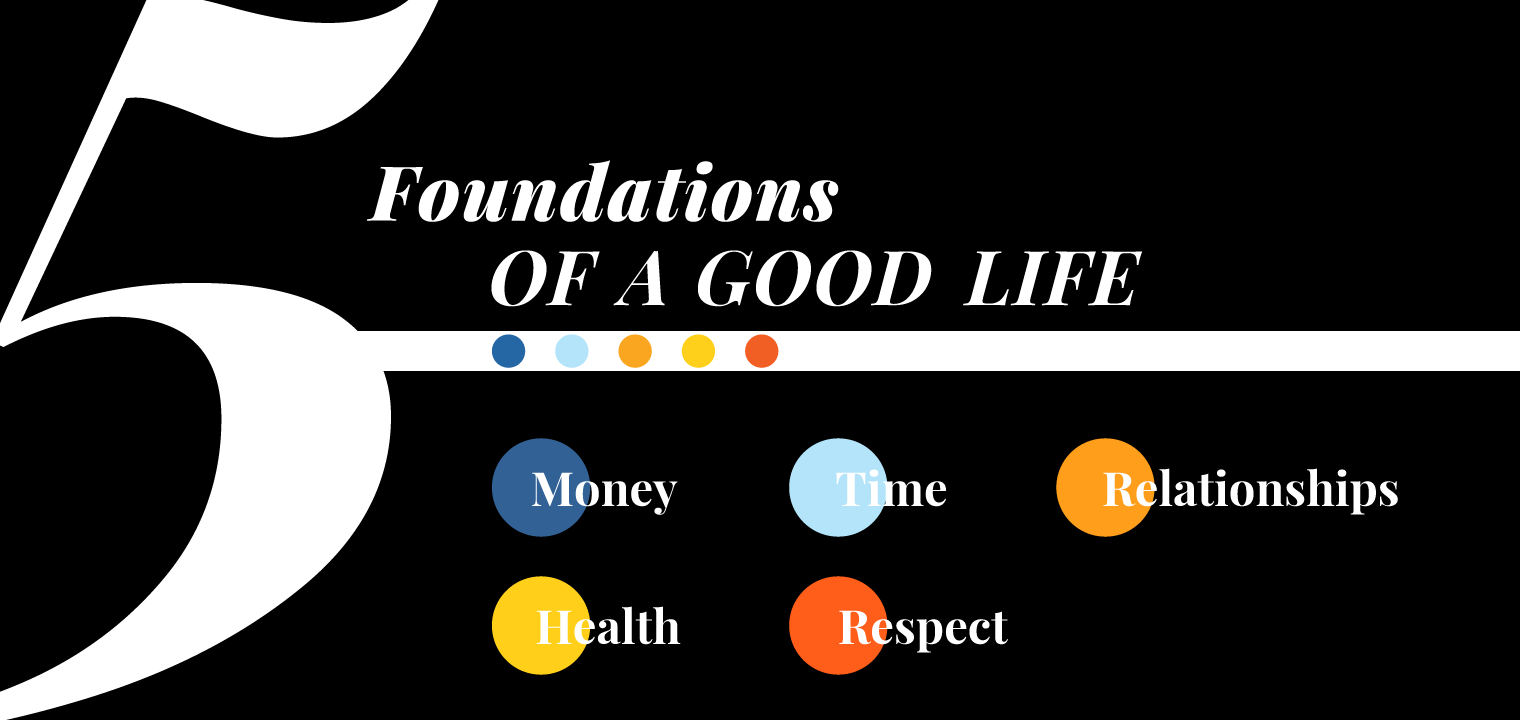

Foundations of a good life

What makes for a “good quality of life?” Since everyone is different, there is no single formula for a good life – that’s the beauty of pluralism. But it seems clear, not least from the extensive research that has been conducted on self-evaluated well-being, that there are five core ingredients for a good quality of life that are held in common:

- Money. A decent, steady flow of income helps families pay their bills and go about their daily lives. Some money put aside – wealth – can help them out in tough times, allow for some investments in their children’s future, and provide some peace of mind. Over the last few decades, middle class incomes, after taxes and benefits, have grown half as fast as for both the rich and poor.

- Time. We need time for well-being, for rest, for relationships, and for the pursuit of our personal passions and interests. That is why people who spend their money in ways that save time are typically happier than those who spend it on goods. Since 1975 middle class couples have increased their joint working hours by two and half months.

- Relationships. Having good relationships is, for most people, the most important ingredient of a good quality of life. As Martin Seligman, professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania puts it, “while relationships are not everything, they are almost everything.” But family instability is rising, and community ties are weakening.

- Health. The 2020 pandemic has been a vivid and even brutal reminder that health is an essential ingredient of a good quality of life. Good physical and mental health has been shown repeatedly to be closely associated with measures of subjective well-being. The U.S. has some concerning trends regarding the mental health of its citizens.

- Respect. Evidence suggests that being treated with respect matters for our well-being. Respect is owed not just to people with whom we have a personal relationship, but to all those we encounter, and indeed to the members of our community more broadly. A lack of respect has led to polarization and discrimination – which have become embedded in institutions and systems.

The importance of these five dimensions was underlined and brought to life by middle-class Americans themselves, in our American Middle Class Hopes and Anxieties Study – a series of focus groups and individual interviews undertaken by our team in 2019 and 2020 in five locations across the United States: Las Vegas, NV; Wichita, KS; Houston, TX; Prince George’s County, MD; and Central Pennsylvania. We have included some quotes from participants in this contract. The full results of this work will be available in forthcoming papers.

New policies, new contract

A good life cannot be delivered, neatly packaged, by the government. The quality of our lives is to a large extent in our own hands – and most of us like it that way. The actions of individuals, communities, and institutions are, in many cases, much more important than public policy. This is a feature of liberal societies, rather than a fault. But it is also nigh impossible to create a good life in a hostile, dog-eat-dog society. Capitalism is the right way to organize an economy, but not a good way to organize a society. All that said, there are also many goals that can and should be pursued through state action. Our view is that in recent years, too little has been asked of government, not too much.

Some signature policies included in our proposed new contract with the middle class are:

- Eliminating income tax for most middle-class families to reward work and reduce inequality

- Scholarships for Service: tuition-free college for national service volunteers to raise skills and strengthen civic society

- Twenty days of guaranteed paid leave per year for all workers to lessen the time squeeze

- Universal access to effective, no-cost family planning to strengthen families

- A national tax on sugary drinks to prevent obesity and improve health

In addition, we support a higher minimum wage, more profit sharing, aligning school hours to working hours, fair scheduling protection, more assistance for nonprofits and local governments, high schoolers attending the naturalization ceremonies of immigrants, Citizens Juries to inform policymaking, a lifelong learning account, universal free school lunches, and free effective therapy for all. Our aim in these pages is to argue for and briefly sketch these and other ideas, not to provide all the policy details; we have provided many references for those who wish to learn more. It is also worth noting that while our goal here was not to reduce the budget deficit, we have been careful not to add to it, either.

As scholars who have worked for a long time on issues of class and inequality, we admit to being worried about the state of our nation. But we are optimistic, too. Perhaps this seems Panglossian given the circumstances in which we write. The brokenness of our society is more visible than ever. But so too, we believe, are the prospects for serious reform. The case for a new contract with the middle class has never been stronger. For once it is not hyperbole to ask: If not now, when?

America can only be as strong as the American middle class. We believe that the new contract we have described here, based on the core principles of partnership, prevention, and pluralism, holds out the promise of a better future for the middle class — and therefore for the nation. Let us know what you think.